‘In the Brewing Luminous’

Champagne, sorbet and cocaine. Who would have guessed, while falling under the spell of Cecil Taylor’s music at the beginning of the 1960s, that these formed the basis of the great pianist’s diet? From listening to Jazz Advance, “Excursion on a Wobbly Rail”, the “Pots”/”Bulbs”/”Mixed” session and the sublimely sombre trio reading of “This Nearly Was Mine”, I had him pegged as an artist of the ascetic variety. How utterly wrong.

Actually, I was given a clue at the end of a post-gig interview in London in 1969, when he asked if I could recommend a good discothèque. As Philip Freeman demonstrates in the course of In the Brewing Luminous, Taylor lived on his own terms, resistant to cliché in his life as much as in his music.

A full-scale biography of Taylor has long been needed, and Freeman’s densely packed 250-page volume is as good a one as we are likely to get. I say “densely packed” because the author has made the decision to include as much detail as possible of all the gigs Taylor played and all the recordings he made throughout his long career, along with impressionistic descriptions, where evidence survives, of how they sounded.

To begin with, I worried that this was going to produce the kind of play-by-play narrative familiar from sporting biographies, where one match or competition follows another in a way that can try the reader’s patience. Eventually my reservations faded to nothing. Apart earning our gratitude for the intrinsic value of having all this information assembled in one place, Freeman inserts enough first-hand testimony from participants and bystanders to bring Taylor, who died in 2018, aged 89, back to life.

In 2016, when the reopened Whitney Museum hosted a season to celebrate Taylor, Freeman interviewed him for The Wire. Although highly articulate and sometimes loquacious to a fault, the pianist was not always the most forthcoming or enlightening of witnesses on the subject of his own career. But enough exists for the author to have pieced together the remarkable story of his early life, his rise to notoriety as the first member of the avant-garde to send ripples through the jazz establishment, and his progress, as Freeman eloquently puts it, “from insurgent to institution”, from enduring the scorn of Miles Davis and others to becoming the recipient of a Guggenheim fellowship in 1973 and a MacArthur “genius grant” in 1991.

Writing about Taylor’s music in descriptive terms is straightforward enough. Almost any would-be Whitney Balliett can raid the adjective cupboard to produce a satisfactory review of a single concert or recording. As many of us have, Freeman makes considerable use of similes and metaphors drawn from the natural world, so there are lots of thunderstorms and tidal waves in his accounts of the sound and effect of Taylor’s music, particularly the solo work. Again, at first I thought this might become wearying. It doesn’t, because there’s a lot of other important stuff going on.

Freeman examines Taylor’s relationships with the music’s facilitators and gatekeepers, such as George Wein, a perhaps unlikely early champion, and the record producer John Snyder, and with the educational institutions where he taught and assembled groups as test-beds for his compositional techniques. This isn’t a book of musicology, so there isn’t much real analysis, but we hear enough from former sideman and students to get a glimpse of a man so supremely musically literate would write his pieces down in alphabetical form — a string of notes, such as D-B-E flat-A-F sharp-G — and give them to players without much else in the way of detail (no note values or registers) or instruction.

Over the course of the book, and without labouring the point, Freeman persuades us that Taylor, far from being a man with a mission to connect modern jazz with the Second Viennese School, as many assumed in the early days, was actually concerned with creating a language based on non-Western rituals and practices.

He could seem perverse. There are several accounts of how he would sometimes rehearse a band relentlessly, searching for something, only to abandon all the preparation once they had taken the stage. But that wasn’t always the case. I have a vivid memory from one night in 1969 of how intently Jimmy Lyons and Sam Rivers, his saxophonists, followed the scores on their music stands while performing his music at Hammersmith Odeon.

Many interesting people slip in and out of this narrative, from Amiri Baraka to Mikhail Baryshnikov to Pauline Oliveros. Some were collaborators, some were friends, some were adversaries. Death, alas, robbed Freeman of the chance to talk to many who would have had something interesting to say, such as Lyons, the Johnny Hodges to Taylor’s Duke Ellington, or Buell Neidlinger, the bassist in his early groups, a man with perfect recall of every session he ever played on, and with pungent views. I wish he’d talked to Evan Parker, who saw the classic Taylor-Lyons-Sunny Murray trio in New York and played with Taylor during the pianist’s stay in Berlin in 1988. But there are enough survivors, albeit inevitably weighted towards the later decades (including the pianist Vijay Iyer, the drummer Pheeroan akLaff and the trumpeter Amir ElSaffar), to provide a pretty rich portrait.

In his later years, Taylor’s performances increasingly involved the dramatic recitation of his poetry, a gloriously forbidding jumble of polysyllabic arcana. I was present one night in the year 2000 at St Mark’s Church on East 10th Street in New York when he shared a Poetry Project evening with Baraka. I had no idea what to make of his poetry. Nor, perhaps, was I meant to. Freeman can’t do much more than briefly describe it, which is not surprising. Impossibly gnomic, fearlessly impenetrable, it probably contained the key to the mystery of Cecil Taylor.

Freeman’s diligence enables him to preserve for us the details of events such as the ceremony surrounding Taylor’s acceptance of the 2013 Kyoto Prize in Tokyo, including a moving description of his duet with the dancer Min Tanaka at the ceremony and the pianist’s words in a subsequent interview: “The question is simply this: is the secret in the symbol of the note, or is it the feeling that exists before you translate the note into music? Music proceeds from within. The note is merely a rather uninteresting symbol that equates to the sound. But sound is always with us.”

Alas, a man posing as a friend and helper managed to separate Taylor from the prize money that went with the Kyoto award: a small matter of $492,725. For a man in his mid-eighties, in increasingly frail physical health, the ensuing legal battle for restitution was traumatic. Eventually he was granted a court-appointed legal guardian, who looked after him until his death.

Not surprisingly, the book becomes more emotionally compelling as it moves towards and through this final chapter. As I finished it, I realised that In the Brewing Luminous (which, of course, takes its title from one of Taylor’s compositions), is a work not just of heft but of sensitivity towards an awkward, sometimes forbidding subject.

Freeman notes that Taylor’s ashes were interred in the Woodlawn Cemetery in the Bronx, also the resting place of the remains of King Oliver, Coleman Hawkins, Miles Davis, Max Roach, Ornette Coleman, and Taylor’s own idol, Ellington, key figures in the tradition to which he made his own tumultuous, enigmatic, sometimes exasperating, but utterly original contribution.

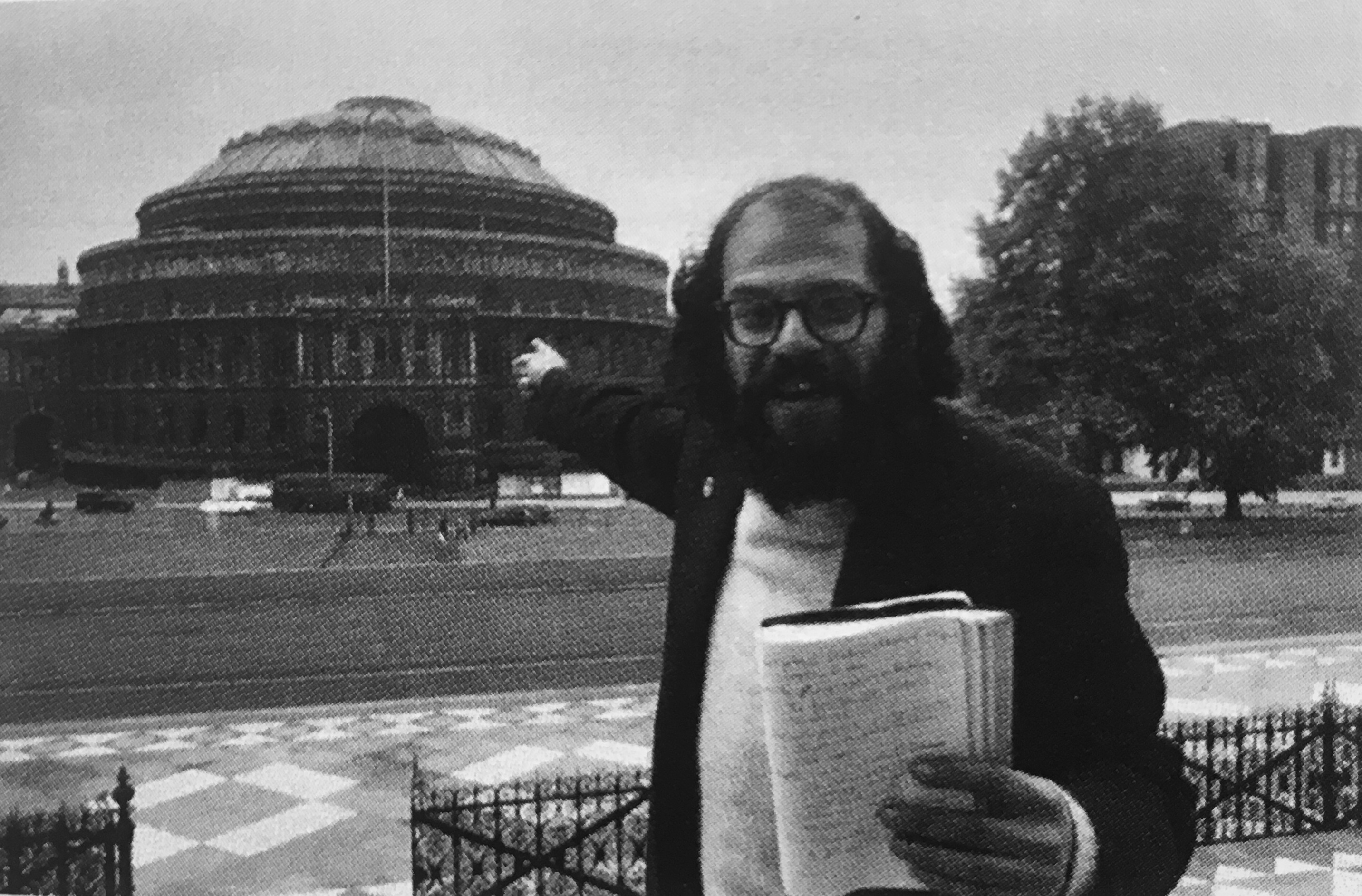

* Philip Freeman’s In the Brewing Luminous was published on July 5 by Wolke Verlag. The photograph of Cecil Taylor was taken by Andrew Putler and is from Jazz: A Photographic Documentary, published by Studio in 1994. A previously unheard 1980 recording of Cecil Taylor with a sextet including Jimmy Lyons and Sunny Murray at Fat Tuesday’s in New York has just been issued by Hat Hut Records in the Ezz-thetics First Visit series.