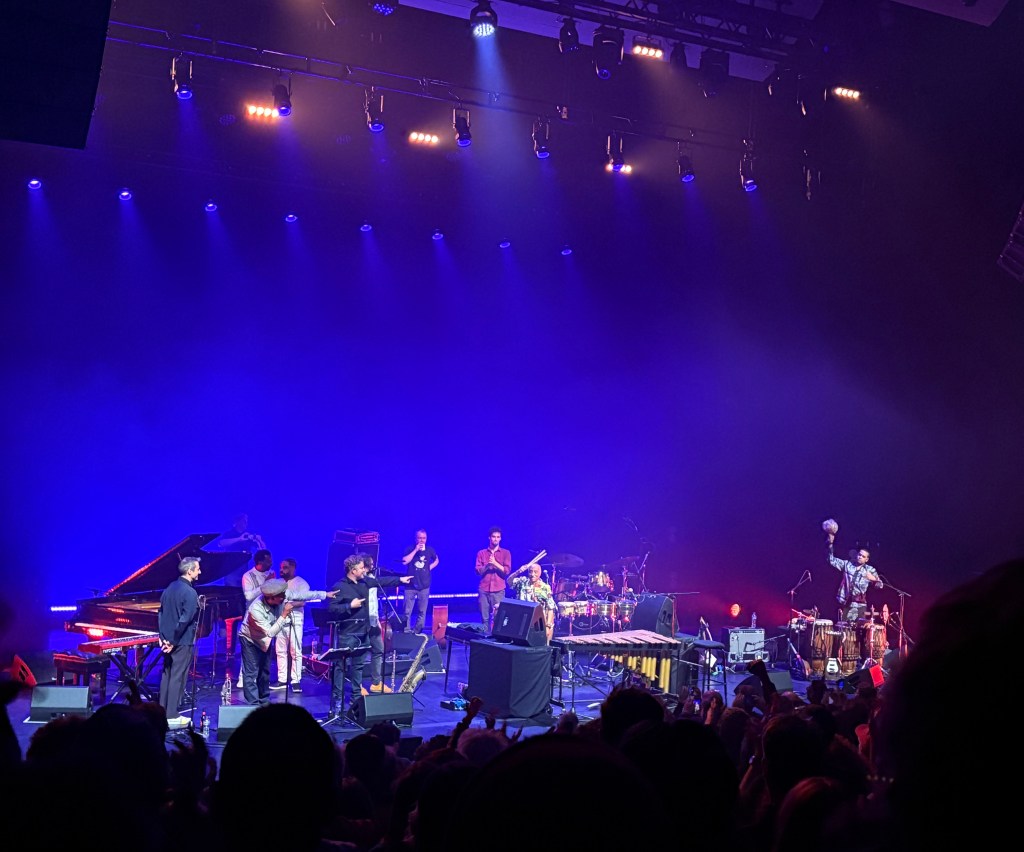

Mulatu Astatke says goodbye

A month shy of his 82nd birthday, Mulatu Astatke brought his farewell tour to a close with two sold-out dates at the start of the EFG London Jazz Festival this week. I went to the first of them, at the Royal Festival Hall, to celebrate the work of the man generally credited with the creation of “Ethio-jazz”.

It takes more than one person to create a genre, but Astatke, who left Ethiopia as a teenager in the late 1950s to study vibraphone, his main instrument, and composition at Trinity College in London and Berklee College in Boston, was certainly a catalyst. He began making records in the US in the 1960s before returning to Ethiopia, where conditions changed after the takeover by a military junta in 1975, restricted Addis Ababa’s lively creative scene. He already had a large hipster following when the use of his music in Jim Jarmusch’s Broken Flowers in 2005 expanded his audience considerably.

On Sunday night he began the concert with Steps Ahead, his seven-piece European band, including such familiar figures as the trumpeter Byron Wallen, the pianist Alexander Hawkins and the double bassist John Edwards. The first half of the 90-minute set featured some of the compositions revived for a recently released album, Mulatu Plays Mulatu, including “Yekermo Sew”, with strong echoes of Horace Silver, and “The Way to Nice”, which plays a game with the James Bond riff. This music sounds like early-’60s hard bop filtered through Ethiopian modes and intonation, infusing it with as distinctive a flavour as the Skatellites and the Blue Notes imparted to similar material in Jamaica and South Africa respectively.

I was struck by the use of Danny Keane’s cello, sometimes strummed like a rhythm instrument, at other times interjecting short percussive phrases with a dry tone, and often combining to powerful effect with Edwards’ bass. It was intriguing to hear Edwards, Hawkins and the saxophonist James Arben delivering solos using the language of free jazz in the context of this mostly riff-based music, and receiving ovations for their efforts. While Astatke was spinning out his mellifluous extended vibes solos over the deep groove provided by the kit drummer, Jon Scott, and the percussionist, Richard Olatunde Baker, on something like “Netsanet”, I felt perfectly contented.

For the second half of the set, the band was joined by two dancers, a man and a woman, and two more musicians, playing the masengo, a single-stringed bowed lute, and the krar, a six-stringed lute. This was more of a folkloric experience, inviting the sort of mass participation that can seem awkward in a modern western concert hall. But it would be wrong to suggest that it was not greatly enjoyed, or that Astatke was not given the warmest and most rousing of valedictory salutes.

* Mulatu Plays Mulatu is out now on the Strut label.

Orphy Robinson must have known he’d had a great idea when he put together an octet to celebrate the music of the late

Orphy Robinson must have known he’d had a great idea when he put together an octet to celebrate the music of the late