The biggest mistake Burt Bacharach ever made was to place an international call to Hal David one day in 1972 and tell him he wanted a bigger share of the five per cent royalty due to the pair from their songs for the film Lost Horizon, a misbegotten musical remake of Frank Capra’s pre-war classic. Until that point the composers of “Anyone Who Had a Heart”, “Do You Know the Way to San Jose?” and so many others had split the proceeds of their work straight down the middle. But suddenly it occurred to Bacharach that here he was, working himself to the bone in the studio on the arduous task of recording the songs and the background score, while David, having done his job by furnishing the lyrics, was down in Mexico, playing tennis. In Bacharach’s view, a 3:2 split would more accurately reflect the relative amounts of effort involved.

The biggest mistake Burt Bacharach ever made was to place an international call to Hal David one day in 1972 and tell him he wanted a bigger share of the five per cent royalty due to the pair from their songs for the film Lost Horizon, a misbegotten musical remake of Frank Capra’s pre-war classic. Until that point the composers of “Anyone Who Had a Heart”, “Do You Know the Way to San Jose?” and so many others had split the proceeds of their work straight down the middle. But suddenly it occurred to Bacharach that here he was, working himself to the bone in the studio on the arduous task of recording the songs and the background score, while David, having done his job by furnishing the lyrics, was down in Mexico, playing tennis. In Bacharach’s view, a 3:2 split would more accurately reflect the relative amounts of effort involved.

David’s answer, quite understandably, was a brusque negative. From the lyricist’s standpoint, it was the suavely handsome and charismatic Bacharach who had already been attracting the lion’s share of the personal publicity accruing from their success; he was the one who appeared in concerts and on television and made his own albums devoted to instrumental albums of their songs. By contrast, David was a charisma-free zone, but the words he provided were certainly as important as the music in what had become known, to his quiet chagrin, as “Bacharach songs”. And that dispute marked, to all intents and purposes, the end of one of the greatest songwriting partnerships in the history of 20th century popular music.

Bacharach tells the story in Anyone Who Had a Heart: My Life and Music, an autobiography ghosted by Robert Greenfield and just published by Atlantic Books. He’s a classic unreliable narrator, a fact tacitly acknowledged by the inclusion of sometimes corrective first-person testimony from ex-wives, lovers and former collaborators, but he leaves us in no doubt that he rues his hot-headed decision to reply to David’s refusal with these words: “Fuck you and fuck the picture.” In the short term, it led to Dionne Warwick suing both of them for their failure to come up with the songs promised for her next album, her first for Warner Brothers; there were countersuits, and the three of them didn’t speak to each other, let alone work together, for 10 years. “It was stupid, foolish behaviour on my part and I take all the blame for it,” Bacharach says now. Later in the book he ruminates on how many great songs might have been lost to that sudden rupture.

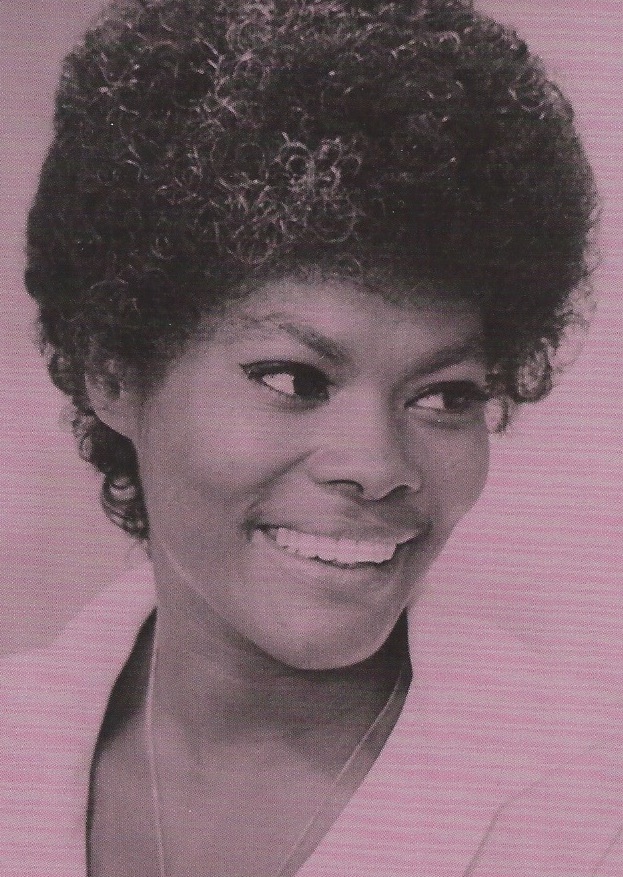

Ah well, the years of full production were wonderful while they lasted. It would be impossible to convey to a young person the shock and awe one felt on hearing Dionne’s “Anyone Who Had a Heart” for the first time in 1963: it sounded like a completely new form of music, something that blended the grown-up sophistication of the great Broadway songwriters with the emotional directness and urgency of the combination of R&B and gospel that was at that moment giving birth to soul music. Bacharach recognises how fortunate he was to find Warwick, the perfect interpreter of their songs, but if there is one thing missing from the book, it is his considered analysis of why black voices were in general so much more effective that white ones on the songs he and David wrote. There were exceptions, of course (one thinks of Dusty Springfield’s versions of their early songs, particularly “The Look of Love”, Herb Alpert’s “This Guy’s in Love With You” or Gene Pitney’s “Twenty Four Hours from Tulsa” and “Only Love Can Break a Heart”), but Warwick, the Shirelles, Lou Johnson, Chuck Jackson and Jimmy Radcliffe added an uptown quality that gave the material a priceless extra dimension.

There’s interesting stuff in the book about Bacharach’s childhood and apprentice years, about his time spent as Marlene Dietrich’s musical director, and a great deal about his four wives — including the actress Angie Dickinson, the second, and the songwriter Carole Bayer Sager, the third — and his many lovers. It’s seldom less than interesting, and when it comes to the description of the life and tragic death of Nikki, his daughter with Dickinson, who was born and lived most of her 30 years with undiagnosed Asperger’s syndrome, it is deeply upsetting.

The stuff about the music is less detailed. I’d have liked much more about the thinking behind, say, his preference for legit-toned rather than jazz-toned saxophones and his liking for twangy guitars, but there are still plenty of nuggets about such topics as his fondness for using a pair of flugelhorns (e.g. on Dionne’s “Walk On By”, which also has a pair of pianos, played by Paul Griffin and Artie Butler), a few enlightening bits and bobs about the sessions in New York and London, and some insights into the variety of approaches he and David employed in order to dovetail their contributions. There doesn’t seem to have been a strict music-first or words-first formula; the constant, we are led to believe, was Bacharach’s insistence on finding the right note and harmonic colouration for each word. It’s a shame they got sidetracked by the lure of Broadway musicals and the movies, a temptation which eventually did for them. The business of crafting their jewel-like individual songs should have been enough, as Bacharach now seems to recognise.

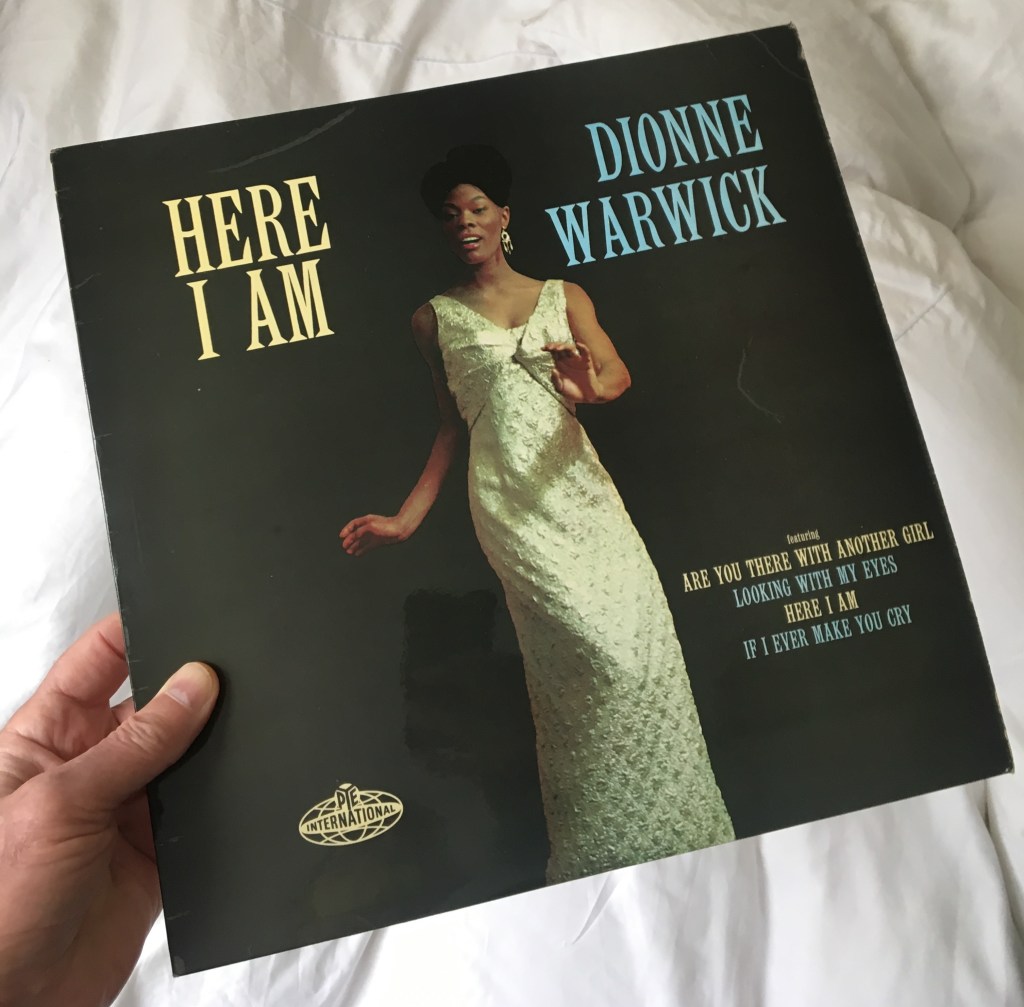

I’m pleased that he devotes a couple of pages to the album he made with Ronald Isley in 2003 for the DreamWorks label. Here I Am, which borrows its title and its lovely title song from my favourite Dionne Warwick LP, is a magnificent recital of mostly familiar material, with quite startlingly exquisite versions of “Alfie” and “Anyone Who Had a Heart” in particular, all recorded live in the studio — vocals and orchestra at the same time, with only the tiniest bits of vocal patching required. Listen to “Alfie”: you won’t hear better singing anywhere, and it was a first take. Unfortunately, as Bacharach relates, the album came out just as DreamWorks was being bought by Universal and got lost in the shuffle. It’s a half-buried classic.

Probably even fewer people heard Bacharach’s last solo album, At This Time, released in 2005. Most of the lyrics were written by Tonio K, and some by Bacharach himself. Interestingly, they express his anger at the crimes of George W. Bush’s neo-con gang. It’s a reminder that he and David also produced a couple of the Sixties’ gentlest protest songs: “What the World Needs Now Is Love” and “The Windows of the World”. What a pity circumstances conspired to silence their collaboration.

Just about to start a short tour of the UK, Bacharach is promoting the book and a new six-CD box called The Art of the Songwriter, whose compilers have made some pretty strange choices, such as the complete absence of anything by Lou Johnson, who came close to becoming the male equivalent of Dionne Warwick, and whose early work with Bacharach and David is compiled on a fine Ace disc titled Incomparable Soul Vocalist. Bacharach is appearing in concert at the Royal Festival Hall in London on Wednesday, Glasgow on Friday, Edinburgh on Saturday, Bournemouth on July 5 and the Festival Hall again on July 7, which is when I hope to hear him.

In the meantime, here’s my all-time Bacharach top 10: 1 Chuck Jackson: “Any Day Now” 2 Dionne Warwick: “(Here I Go Again) Looking With My Eyes (Seeing With My Heart)” 3 Ronald Isley: “Alfie” 4 Burt Bacharach Orchestra: “Wives and Lovers” 5 Fifth Dimension: “One Less Bell to Answer” 6 Dionne Warwick: “If I Ever Make You Cry” 7 Lou Johnson: “Kentucky Bluebird (Message to Martha)” 8 Herb Alpert: “This Guy’s in Love With You” 9 Dusty Springfield: “The Look of Love” 10 Jimmy Radcliffe: “Long After Tonight is All Over”.