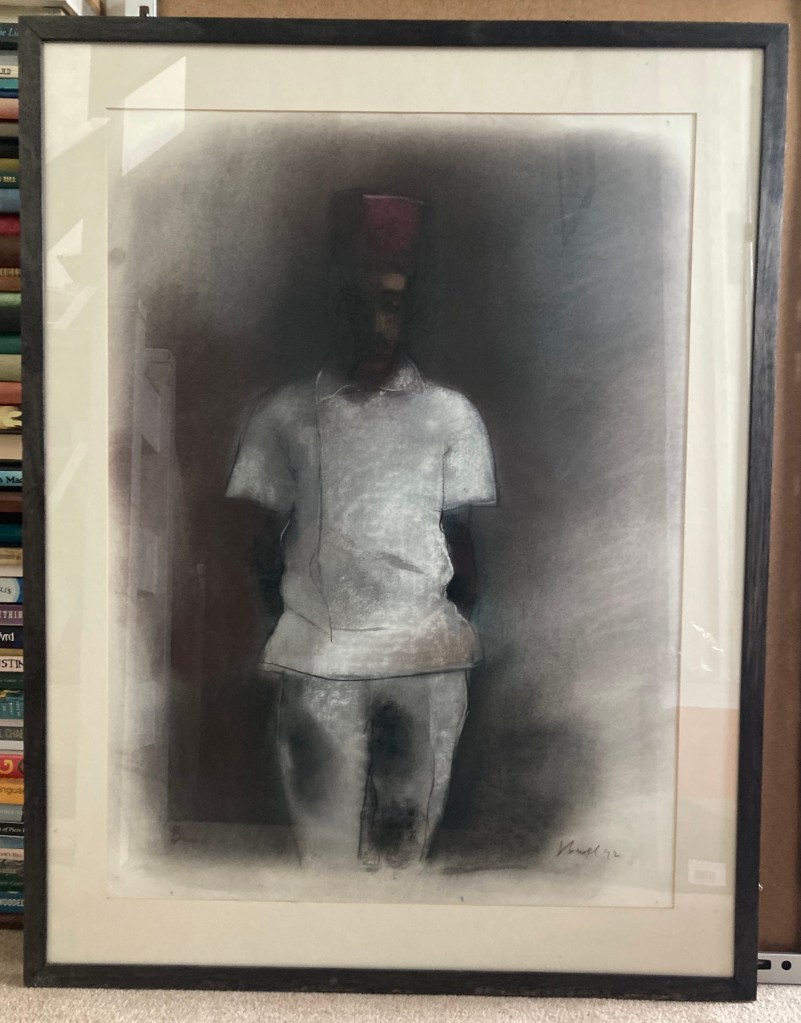

A portrait of Bud

There’s this portrait that I bought about 30 years ago from an English artist called Johnny Bull. At the time, he was concentrating on jazz musicians: Miles, Coltrane, Monk. I liked his work, so I invested a couple of hundred quid in one of the less obvious subjects, a large pastel portrait of the bebop piano master Bud Powell. It hung on a wall in the house for a while but then I got uncomfortable with it and put it away. It emerged recently and I’ve been thinking about it a lot.

Bud was one of jazz’s great tragedies as well as one of its great masters. He was a classically trained prodigy from a highly musical family. But in 1945, aged 20, after being arrested while drunk on the streets of Philadelphia one night after a gig with the trumpeter Cootie Williams’s big band, he was beaten on the head. The effect was to change his personality, putting him in and out of mental institutions, where he was subjected to electro-convulsive therapy.

Some of those who heard him in his teens said his playing was never quite the same after the beating. But still it was good enough to make him the leader among modern jazz pianists in the late ’40s and early ’50s, the only one who could take the stage with Charlie Parker, Fats Navarro and Max Roach and exist absolutely on their level, matching their creativity. At his best — in his 1947 trio session released as a 10-inch LP on the Roost label, for example — he was incomparable, although drugs prescribed for what was then known as manic depression sometimes dulled his mind and his edge. But he remained capable of composing, alongside bop standards like “Wail” and “Bouncing with Bud”, such extraordinary pieces as “Parisian Thoroughfare” and “Glass Enclosure”.

After several years in Paris, where he had a trio with the great Kenny Clarke on drums and the French bassist Pierre Michelot and was looked after for a while by the writer, commercial artist and amateur pianist Francis Paudras, he returned to New York in 1964. He died there two years later, aged 41, of the effects of tuberculosis, exacerbated by alcoholism and general neglect.

If you want to know about Bud, there are several good biographies, including Paudras’s Dance of the Infidels (Da Capo, 1998) and Peter Pullman’s exhaustively researched Wail (available on Kindle). And I recommend an hour-long documentary called Inner Exile, made for French television in 1999 and now on YouTube, directed by Robert Mugnerot and featuring marvellous performance footage as well as interviews with those close to him. (The great René Urtreger, who made an album of Powell’s compositions in Paris in 1955, says of his hero: “He was not made to live in this society.”)

I contacted Johnny Bull via email a few days ago, wanting to talk about his portrait. As you can see, it shows Bud wearing a fez and what looks like some kind of hospital uniform. When I first saw it, it seemed a powerful way of dramatising the pathos of his story. So, after we’d become reacquainted, I told Johnny about my dilemma. It’s a very fine piece of art, and quite beautiful, but it brings too much sadness to a domestic setting. Exhibiting it in a public environment, like a gallery or museum, might not be the right way to introduce Bud to people who don’t know anything about him. It illustrates one aspect of his life with great sensitivity but gives no indication of what he brought to the world, which is why it wouldn’t really work on the wall of a jazz club, either.

The artist agreed. “It’s a distressing picture,” he said. “He looks such a lost soul. I made a painting of Lester Young once, towards the end of his life, and it was too disturbing to keep looking at, so I quite understand your feeling.”

Johnny Bull loves and understands the music. His intentions when he made the portrait were beyond reproach, his response to the subject was anything but superficial, and his execution was impeccable. I bought it because it moved me. But I have no clear idea of what its fate should be now. It seems wrong for it to spend any more years stacked away in my house. Maybe I’m writing this in the hope that someone will propose a solution. Failing a better idea, I’ll probably just give it back to the artist, who can put it in his archive. Then, one day, someone else will have to make the decision.

Bud Powell never made being a genius look easy. Fifty years ago tomorrow — on July 31, 1966 — his death at the age of 41 put an end to an existence that seems to have been defined by two factors: first, his extraordinary talent; second, an incident that took place when he was not even 21, and which began the process of stifling his brilliance.

Bud Powell never made being a genius look easy. Fifty years ago tomorrow — on July 31, 1966 — his death at the age of 41 put an end to an existence that seems to have been defined by two factors: first, his extraordinary talent; second, an incident that took place when he was not even 21, and which began the process of stifling his brilliance.