A weekend with Booker T

It was a warm evening, and the air conditioning had packed up. An hour before midnight last Friday, Ronnie Scott’s Club was like a sauna. “That’s when it started to feel authentic,” Booker T Jones would say later. “Just like the places I used to play.” But the air-con failure wasn’t the only good omen.

When there’s a Hammond organ in the house, the best place to be is as close as possible to one of its Leslie speakers — those pieces of wooden furniture, the size and shape of a small refrigerator, containing rotating horns which, at the flick of a switch, provide the instrument with its distinctive and heart-stirring whirr and churn.

It’s a lesson I learnt during my teenage years, when the clubs were small and the stages were low and you could get up close to the likes of Georgie Fame, Graham Bond and Zoot Money. So I was extremely pleased when the maitre d’ at Ronnie’s led me to a seat at the side of the stage, a few feet away from one of the two Leslies hooked up to Booker T’s B3. What would normally have been a rather indifferent vantage point suddenly seemed like the best spot in the house.

Booker T Jones is one of my all-time heroes. Like many, I remember the thrill of hearing “Green Onions” for the first time; its special magic has never faded. And its B-side, a sinuous slow blues titled “Behave Yourself” (originally intended as the A-side), hinted at other dimensions of musicianship. As the years passed I discovered that every note he recorded was worth hearing. All the original MGs’ Stax albums, from Green Onions in 1962 to Melting Pot in 1971, contained something wonderful — and I’m very fond of the two reunions that followed Al Jackson Jr’s tragic death, Universal Language (Asylum, 1977) and That’s the Way It Should Be (Columbia, 1994), with Willie Hall, Steve Jordan and James Gadson replacing the peerless Jackson at the drums. Booker went on to prove, with Bill Withers’ Just As I Am in 1971, Willie Nelson’s Stardust in 1978 and the Blind Boys of Alabama’s Deep River in 1992, that he is a producer of marvellous sensitivity. He remained a wonderfully sympathetic sideman, too: for the proof of that, just listen to “Sierra”, a gorgeous song from Boz Scaggs’s 1994 album, Some Change.

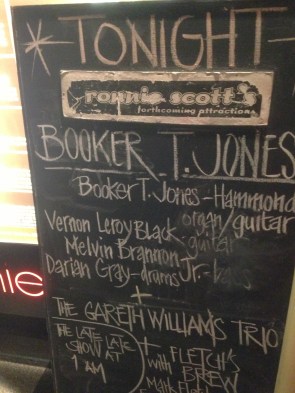

So he’s someone I always look forward to seeing, and on Friday — at the second of four nights (and eight shows) on Frith Street — he delivered a 75-minute set that ranged through his entire history, from that imperishable first hit (recorded when he was a 17-year-old high school student) and the MGs’ great “Hip Hug Her” through Stax/Volt favourites like “I’ve Been Lovin’ You Too Long”, “Born Under a Bad Sign” and “Hold On, I’m Comin'” to pieces from his recent albums: “Hey Ya” from Potato Hole, “Walking Papers” and “Everything is Everything” from The Road From Memphis, and “Fun”, “Feel Good ” and “66 Impala” from the new one, Sound the Alarm. His three-piece band, recruited from the Bay Area, supplied plenty of energy and all the right licks. He sang a bit, in a range-limited voice, and played guitar on a few of the tunes. But when he let the Hammond and the Leslies rip on an encore of “Time is Tight”, the speaker horns spinning faster inside those plywood cabinets, I was somewhere close to heaven.

On Saturday afternoon he returned to the club for a question-and-answer session in front of an audience, showing himself to be a thoughtful and genial man. Sitting at the Hammond, he played snatches of “Green Onions” and “Ain’t No Sunshine”, and just a handful of bars from each was enough to send a thrill through his listeners. Among the things we were told was that Ray Charles’s “One Mint Julep” was the record which led him to conclude that the electric organ would shape his destiny. And there was an interesting answer to a question from my friend Martin Colyer (check his blog: http://www.fivethingsseenandheard.com), who wanted to know how he had come to play bass guitar on Dylan’s “Knockin’ on Heaven’s Door” in 1973. As part of his explanation, Booker told us that he had first been recognised in the Memphis music community through playing bass in the house band at the Flamingo Room on Beale Street, and at that stage — despite his proficiency on keyboards, oboe, clarinet, baritone saxophone and trombone — it was as a bass player that he originally expected to make his career.

Four years ago, when the magnificent Potato Hole came out, I interviewed Booker for the Guardian (it’s here, accompanied by Eamonn McCabe’s fine photograph, taken the same day). Meeting your heroes for the first time is always a perilous business, but I came away from the encounter feeling I now admired the man as much as the musician.

Some bits of the interview didn’t make it into the paper, for reasons of space, so here, for the first time, are his remarks on a couple of topics. First, I asked him whether, as a teenage musician with an inquiring mind in the clubs of Memphis, he’d been familiar with the generation of gifted local modern jazz players that had included the saxophonists Frank Strozier and George Coleman, the trumpeter Booker Little and the pianist Harold Mabern. His answer was unexpectedly illuminating.

“I did,” he said. “They were two or three years ahead of me. Same town, same neighbourhood. I knew who they were. We went through the same doors. But I reached a day, one day, I don’t remember exactly when it was, that I had to ask myself, ‘Can I do this? Will I, in my lifetime, be able not only to play the music but live the lifestyle? Is that who I am?’ I realised, no, it’s not who I am. That’s who Jimmy Smith is, or John Coltrane. I don’t have the resolve, I don’t have the discipline. But even if I did, is that me? No, because I also like to play piano and guitar and trombone and I like to arrange and I also like country music and classical music — so I’m somebody else. I’m not that. And I stopped the pursuit at an early age.

“It broke up some friendships that I had, but I knew it was the right thing for me to do. A very close friend said to me, ‘What are you doing, man? How can you go over to Stax and play that stuff? Is it the money?’ If I’d been hanging out with a Sonny Stitt, that’s what he would have said to me. It was like a club, almost. I talked to Herbie Hancock about it, and to the bass player Stanley Clarke, and I know I couldn’t have done it. I’d have been able to get the technical chops, with practice, but I couldn’t have lived the lifestyle.”

So instead of another Memphis bebopper, we got a man capable of creating something like the arrangement of Willie Nelson’s “Georgia On My Mind”, its wonderful simplicity capped by a coda in which the rhythm and strings are joined by a horn section, vamping gently through the fade-out. He was delighted when I mentioned it as a special favourite.

“I’m so glad you said that,” he responded, “because it took so much time and money to put that on, but I could not get away from the inclination to do that. We went through the whole song with just the band and some strings, but at the very end I just needed to do that. It was expensive — a full complement of horns, and I don’t think we did any other songs at the session. It was an indulgence. At the time it wasn’t a big-selling record. It was a little bit of a struggle and I really appreciate that you like it.”

Even when he adds a horn section to the budget, however, the idea of excess is completely alien to Booker T’s temperament. He is a musician whose presence guarantees a measure of restraint and economy, the hallmarks of all those wonderful MGs records. “I don’t think it could have been any four guys,” he said of the band with whose name his own will be forever linked. “The one thing we had in common was a commitment to making the music simple and funky. It never got so complicated that it was inaccessible to most people. Not to say that complex music isn’t accessible or beautiful, but one way to access beauty is through simplicity.”

On the way out of Ronnie Scott’s on Friday night I bumped into Bryan Ferry, who was with three of his four sons and their girlfriends. He had taken them to listen to a musician he himself had first seen on the legendary Stax/Volt tour in 1967. Now that’s my idea of good parenting.