Young but daily growing

“It was difficult to tell what song he wrote and what song he didn’t write, because sometimes I noticed that he said he wrote a song and he didn’t, and other times I thought he didn’t write a song and he did.“

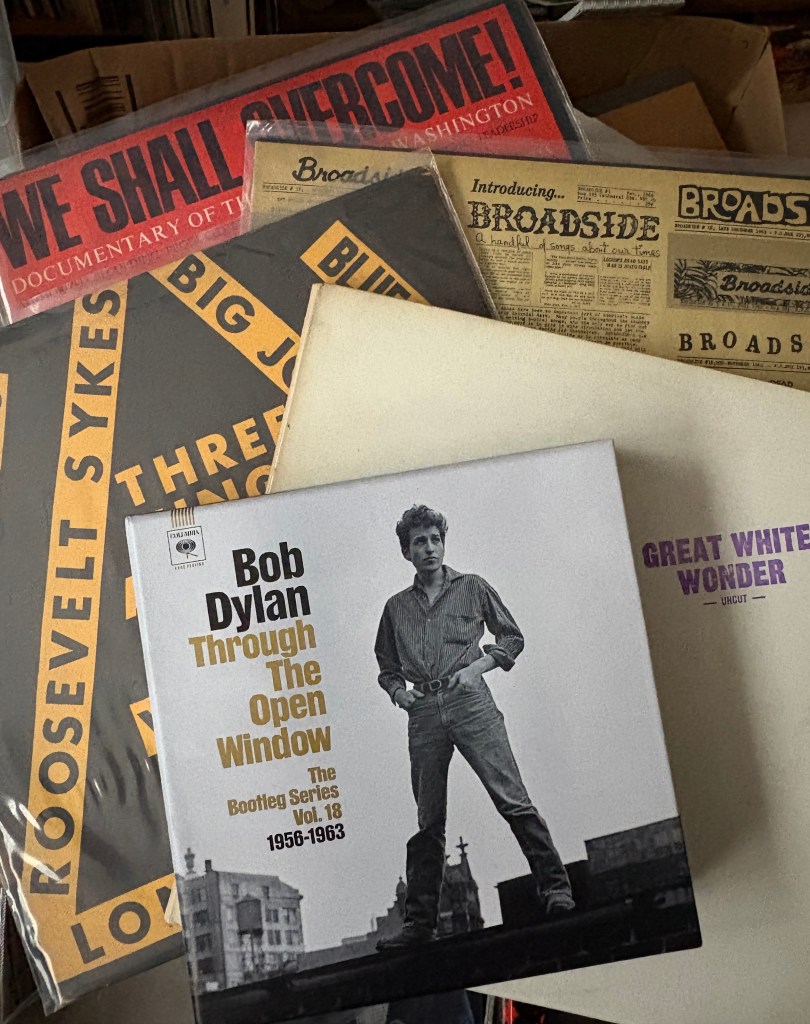

Those words have been in my head while listening to the eight CDs and 139 tracks of Through the Open Window, the 18th volume of Bob Dylan’s Bootleg Series, which arrived a couple of weeks ago. A quote from his boyhood friend John Bucklen, it’s a perceptive early observation about Dylan’s approach to making music: a process of listening, absorbing, blending, modifying and recombining in which borrowed and created materials become one and become new. For him, that’s been a permanent process since he first tuned in to the radio and heard Little Richard.

This new set covers his early years. It begins in 1956 with a 15-year-old schoolboy in Minnesota, taping songs with his pals, and ends in 1963, when he’s standing on the stage at Carnegie Hall, in front of a full house, a 22-year-old at the apogee of his first incarnation, feeling the warm glow of real fame.

I don’t know whether or not it’s the “best” volume of the series to date, but it certainly fills me with a powerful set of emotions. While listening to it, I sent an old friend a message saying that it made me realise how lucky I’d been to live my life alongside his. I’m six years younger than Dylan, so I was 16 when I first heard Freewheelin’ in 1963; for members of my generation who discovered him early, he’s been a unique kind of companion, and still is. Through the Open Window does a good job of showing how that came about.

Over about eight hours, we see continuous progression, evolution, growth. We hear Dylan honing his art as an interpreter of the hellhound-haunted blues (a clenched “Baby Please Don’t Go”, “Fixin’ to Die”, “See That My Grave Is Kept Clean”), hooking his young boho audiences with protest ballads based on specific stories (the incendiary “Emmett Till”, the rousing “Davey Moore”, the plodding “Donald White”), playing harmonica with blues elders Victoria Spivey and Big Joe Williams on Spivey’s album Three Kings and a Queen, practising singing in an older person’s voice and inhabiting traditional material with an astonishing level of empathy (“Young But Daily Growing”, “House Carpenter”, “Moonshiner”, the transcendent 1962 Gaslight version of “Barbara Allen”), and carefully building his own legend (“Bob Dylan’s Blues”, “Bob Dylan’s Dream”, “Bob Dylan’s New York Rag”).

You hear how the droning blues jams — and perhaps the influence of John Lee Hooker, with whom he shared the bill at his first significant New York booking, at Gerdes Folk City in April 1961 — inform a certain strand of songs he soon began to write: “The Ballad of Hollis Brown”, “North Country Blues”, “Masters of War”. Songs about bleak, blasted landscapes, both external and internal. When I listened to those songs in 1963-64, I’m sure that somewhere in my mind I was making a connection with what John Coltrane was doing at the same time. Not a literal connection; something beyond that, to do with stretching structures to fit the times we were living in. A year later, and just beyond the time-frame of this set, that strand of songwriting would lead Dylan to the unsurpassable achievement of “It’s Alright, Ma (I’m Only Bleeding)”.

All this comes through loud and clear on a set thoughtfully assembled by the writer Sean Wilentz (who contributes an impeccable essay to the accompanying hardback book) and the veteran producer Steve Berkowitz, particularly in the performances recorded in friends’ homes and small clubs. We hear Dylan trying things out: using humour to beguile his listeners, sometimes telling tall stories to embellish his myth but also unafraid to acknowledge his sources. Introducing “Tomorrow Is a Long Time” — still a work in progress — into a tape recorder at the home of his friend Dave Whitaker in Minneapolis in August 1962, he seems to drop his guard: “My girlfriend, she’s in Europe right now, she’s sailed on a boat over there and she’ll be back September 1st, but till she’s back I never go home and it gets kind of bad sometimes. Sometimes ir gets bad, most times it’s doesn’t. But I wrote this specially thinking about that.”

Suze Rotolo, the “girlfriend” in question, is a presence in many of these songs. She was also an unheard presence in the tender version of “Handsome Molly” recorded at Riverside Church on the Saturday afternoon in July 1961, which is when they first met (“He comes from Gallup, New Mexico,” the MC tell us). The accompanying book contains some lovely outtakes from Don Hunstein’s Freewheelin’ cover shoot in the snow on Jones Street to go with the outtakes from the recording sessions; an astounding “Ramblin’ Gamblin’ Willie” seems to be setting him off on the path that led a dozen years later to “Lily, Rosemary and the Jack of Hearts”.

A few of the selections are notable more for their historical interest than their musical value, which is fine. They’d include the very first track, a snatch of Shirley and Lee’s “Let the Good Times Roll” recorded with Bob on piano and his friends Larry Keegan and Howard Rutman joining him on vocals in a St Paul music shop in 1956; the surviving fragment of “The Ballad of the Gliding Swan” from his first visit to London in early 1963, engaged to appear in the TV play Madhouse on Castle Street for the BBC; and the versions of “Only a Pawn in Their Game” and “Blowin’ in the Wind” performed at the SNCC voter registration rally in Greenwood, Mississippi in the summer of 1963.

The live recordings include extended extracts from his most significant early New York concerts, including the poorly attended Carnegie Chapter Hall on November 4, 1961 and the sold-out Town Hall show on April 12, 1963. It all leads — and I firmly recommend listening to the set in sequence — to two CDs devoted to the complete Carnegie Hall concert of October 26, 1963, in which the dimensions of his talent are fully revealed.

He comes to the concert while putting the finishing touches to his third album, The Times They Are A-Changin’, which won’t be released for another three months. So the audience is unfamiliar with some of these songs. He hits them straight off with the title song, then “Hollis Brown”, “Boots of Spanish Leather”, “North Country Blues”. There are great new songs that won’t be officially released: “Lay Down Your Weary Tune”, “Seven Curses”, “Percy’s Song”, “Walls of Red Wing”. When he talks, he’s charming and confident and tells some funny stories and in this formal setting he achieves the kind of audience rapport he’d worked hard to establish at the Gaslight or Gerdes, drawing sympathetic laughter when he has trouble with his microphone and mid-song applause when, in “Davey Moore”, he sings about boxing being banned by the new Cuban government (temporarily, as it turned out).

And he finishes with this sequence: “With God on Our Side”, “Only a Pawn in Their Game”, “Masters of War” (that one being from Freewheelin’, of course), “The Lonesome Death of Hattie Carroll” and “When the Ship Comes In”. Just imagine hearing four of those songs for the first time in that climactic five-song fusillade of rage and revelation. The controlled intensity of his delivery comes through as powerfully as it must have done that night. It’s electrifying, even at more than 60 years’ distance.

Here are some lines he wrote as part of a long poem for the sleeve of Peter, Paul and Mary’s album In the Wind, the one that included “Don’t Think Twice, It’s Alright”, “Quit Your Lowdown Ways” and “Blowin’ in the Wind”, released in 1963:

Snow was piled up the stairs an onto the street that first winter when I laid around New York City / It was a different street then — / It was a different village — / Nobody had nothin / There was nothin t get / Instead a being drawn for money you were drawn / for other people —

It is ‘f these times I think about now — / I think back t one a them nites when the doors was locked / an maybe thirty or forty people sat as close t the stage as they could / It was another nite past one o clock an that meant that the tourists on the street couldn’t get in — / At these hours there was no tellin what was bound t happen — / Never never could the greatest prophesizor guess it — / There was not such a thing as an audience — / There was not such a thing as performers — / Everybody did somethin / An had somethin to say about somethin —

Most of all him. And it’s all here.