Miles à l’Olympia

Miles Davis arrived in Paris on the morning of November 30, 1957 for a tour booked by a local promoter, Marcel Romano. He was met at the airport by the singer and actress Juliette Gréco, whose lover he had become during his first visit to France, in 1949, and by the young film director Louis Malle, who wanted him to provide music for the soundtrack to his film Ascenseur pour l’échafaud.

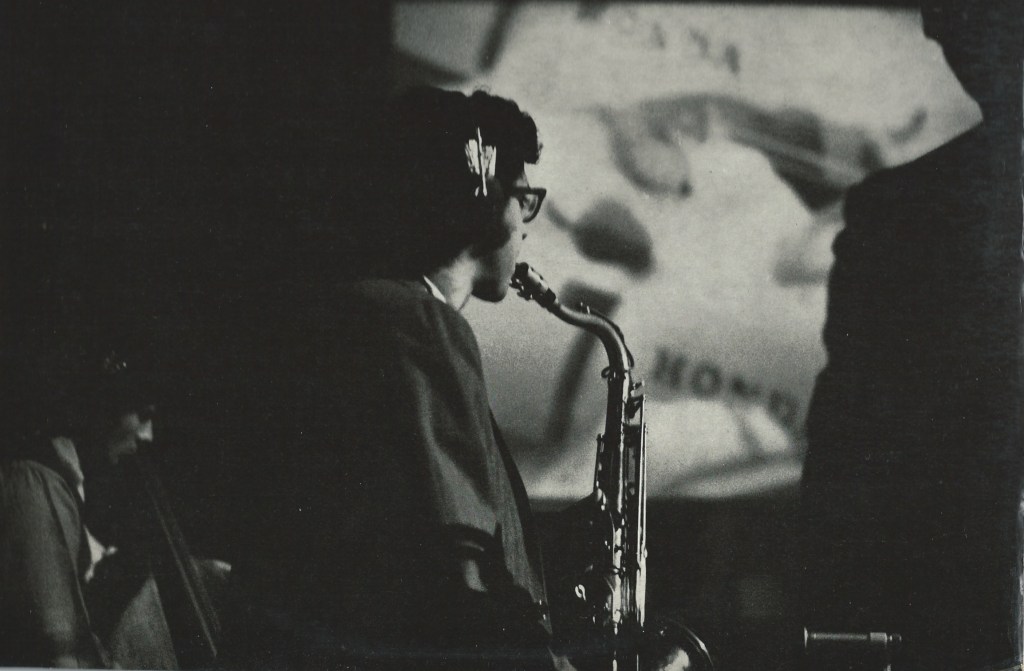

That same night the tour began at the historic Olympia music hall on the Boulevard des Capucines, with Miles at the head of a band completed by the 20-year-old Franco-American tenor saxophone prodigy Barney Wilen, the great American drummer Kenny Clarke, and two excellent French musicians, the pianist René Urtreger and the bassist Pierre Michelot. They performed, as Urtreger told his biographer, Agnès Desarthe, “sans répétition” — without rehearsal.

The soundtrack was recorded on December 4, with the same quintet; it was a turning point in Miles’s music, representing a move away from the standard ballads-and-blues repertoire towards pieces of indeterminate length based on minimal harmonic information rather than closed-loop chord sequences, played live in fragments as Davis watched the film being projected on to a screen in the studio.

Meanwhile, however, the material was more conventional when the band played at the Olympia and at another concert in Amsterdam’s Concertgebouw a few days later, followed by a return to Paris for three weeks at the Club Saint-Germain, apparently arranged when Romano failed to secure the concert bookings across Europe for which he had been hoping. After a concert in Brussels on December 20, Miles flew back to New York, where he began putting together the sextet that would record Milestones early in the new year.

The Amsterdam concert was recorded for radio broadcast, and has been bootlegged several times, most recently on a CD on the Lone Hill label, with lamentably anachronistic packaging and a rather brittle, toppy sound. No complete recording of the Olympia concert was known to exist until, after Romano’s death, his nephew and heir found a set of reel-to-reel tapes among his possessions. He sold them to Jordi Pujol, the Barcelona-based specialist in historical reissues, who commissioned the audio engineer Marc Doutrepont to restore and master them. Doutrepont has achieved a sound as good as the best live recordings of the time: true, clear, warm and perfectly balanced.

Davis and Clarke were old friends and colleagues, and the trumpeter had played with Urtreger and Michelot during his second trip to Europe with the Birdland All Stars, 12 months earlier. Wilen was new to him, but the whole band sounds at ease from the start of their first appearance as a unit. They play a dozen pieces: “Solar”, “Four”, “What’s New”, “No Moe”, “Lady Bird”, “Tune Up”, “I’ll Remember April”, “Bags’ Groove”, “‘Round Midnight”, “Now’s the Time”, “Walkin'” and “The Theme”.

The American writer and musician Mike Zwerin, a steel baron’s son who had played trombone with Davis’s nonet at the Royal Roost in 1948 (aged 18!), was in the audience at the Olympia. Much later Zwerin wrote that the concert had begun with “Walkin'” and that — “in an entrance worthy of Nijinsky” — Miles appeared on stage only midway through that opening tune, to wild applause. No sign of any such thing here.

Miles’s tone and attack were at their most exquisite at this time, between the sessions for Miles Ahead and Milestones, the alertness of his mind ensuring that the poignancy of his sound never became self-indulgent. His solo on “Four” is the sort of thing, like his improvisations on the studio versions of “Milestones” and “So What”, that could be transcribed and studied for the details of its nuanced perfection. He takes “What’s New” as a solo ballad feature, producing elegant variations that can be listened to over and over again.

Wilen, precociously poised and inventive, gets Tadd Dameron’s “Lady Bird”, “I’ll Remember April” and a bouncy “Now’s the Time” to himself with the rhythm section. They are respectively the fifth, seventh and tenth tracks on the album, making me wonder if this is the same order as the actual set list. Would Miles have left the stage and returned so often? Given that he had only stepped off a transatlantic flight a few hours earlier, perhaps so.

Other joys include the trumpeter’s intense blues playing on “Bags’ Groove” and his relaxed exchanges with the immaculate Clarke on Sonny Rollins’s “No Moe”. A couple of fluffed phrases at the start of “Walkin'” are rare blemishes on a a release whose artistic value is the equal of its historical interest. If you love Miles, don’t miss this.

* The Miles Davis Quintet’s In Concert at the Olympia Paris 1957 is on Fresh Sound Records. The uncredited photo is from the booklet accompanying the album. If you want to know why the soundtrack to the Louis Malle movie — released in the UK as Lift to the Scaffold — was such a significant moment in Davis’s career, you might like to read the book after which this blog is named: The Blue Moment: Miles Davis’s Kind of Blue and the Remaking of Modern Music (Faber & Faber).