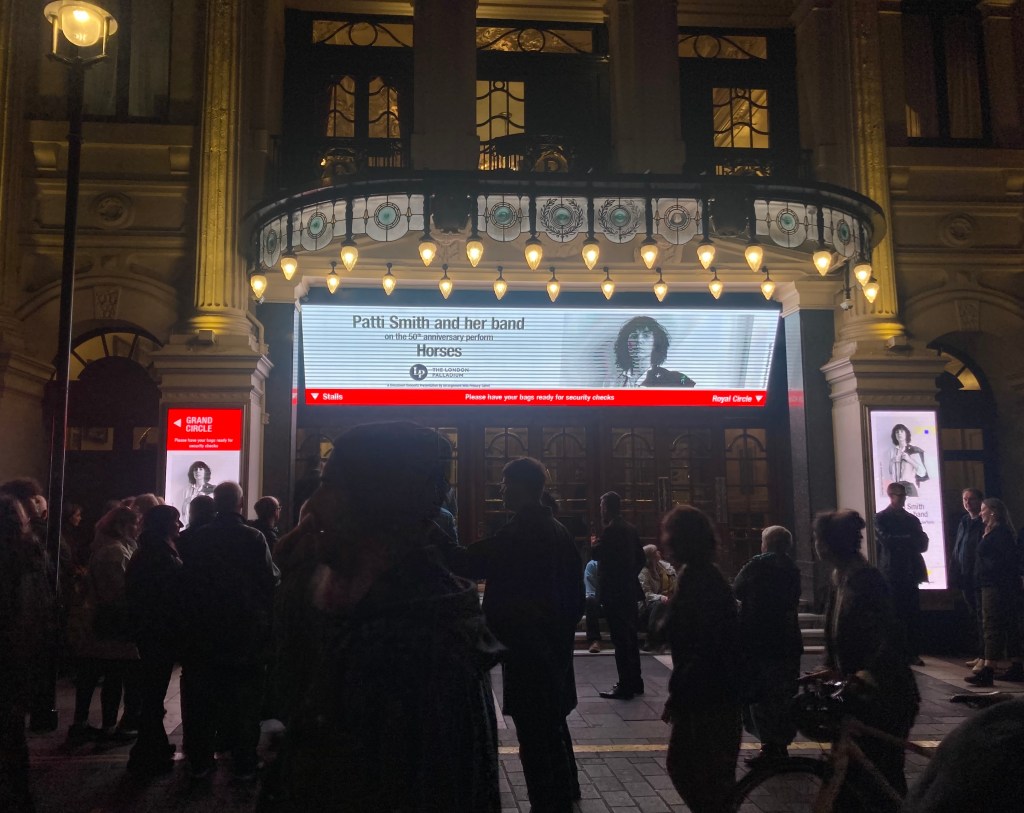

At the London Palladium

Two poets took the stage at the London Palladium this week. The first, Patti Smith, was celebrating the 50th anniversary of the release of the epochal album Horses by playing it all the way through with a band including two of her original confrères. The second, Al Stewart, had made it part of his farewell tour, and thus his final appearance in the city where he once shared a flat with the young Paul Simon and had a residency at Bunjie’s, a folk club a shortish walk across Soho from where he was saying his goodbyes.

Smith is 78. Stewart is 80. Horses came out in 1975, the year before Stewart enjoyed his biggest hit with the title track from Year of the Cat. Both drew full houses — Smith on two nights running — and performed with a vigour that reanimated the work of their youth.

We know Smith as a poet who rammed literary and musical forms together to great and lasting effect. Stewart’s success in turning big subjects — the Basque separatist movement, the French Revolution, Operation Barbarossa — into long narrative folk-rock songs reflected a creative use of the early impact of Bob Dylan on his songwriting. But where the enduring glamour of the New York era of CBGB and Max’s Kansas City ensures Smith’s continuing credibility, Stewart’s soft-rock associations have probably restricted his following to his original audience. There was no measurable difference in the enthusiasm that greeted both artists on a celebrated stage.

If the guitarist Lenny Kaye and the drummer Jay Dee Daugherty provided valued historical support for Horses, assisted by Jackson Smith and Tony Shanahan on keyboard and bass guitar, Stewart (and his four-piece band from Chicago, the Empty Pockets, plus the saxophonist/flautist Chase Huna) benefited from the guest presence of his old collaborator Peter White, who added beautiful guitar decoration to “Time Passages”, which he co-wrote, and “On the Border”, and remodelled the rhapsodic piano introduction — including “As Time Goes By” — to “Year of the Cat”.

To be honest, I hadn’t listened to Stewart for decades before last night. I bought the tickets as a treat for my wife, who knew him a little in Bristol folk scene of the late ’60s and remembers once giving him a lift to London. But as thrilled as I was to hear Smith declaiming “Redondo Beach” and “Birdland”, I was just as beguiled by Stewart’s “The Road to Moscow” and “The Dark and the Rolling Sea”.

Today Smith, of course, looks even more like a poet than she did in 1975. Stewart, who lives in Arizona, now resembles someone who might be the secretary of the local bridge club. Good on both of them.