The Wrecking Crew

Roger McGuinn tells a great story in the course of The Wrecking Crew, Denny Tedesco’s film about the Hollywood session musicians behind countless hits of the ’50s, ’60s and ’70s. He’s recalling the frustration of the other members of the Byrds when they discovered that they’d been replaced for the recording of “Mr Tambourine Man” by a group of session men, including Leon Russell and Hal Blaine. McGuinn himself was permitted to sing and play 12-string guitar on the track, which was completed in a couple of passes. He was the only Byrd on the record. A few months later, now established as one of the world’s biggest groups, the whole band were allowed into the studio to play on “Turn, Turn, Turn”. They needed 77 takes. Enough said.

Roger McGuinn tells a great story in the course of The Wrecking Crew, Denny Tedesco’s film about the Hollywood session musicians behind countless hits of the ’50s, ’60s and ’70s. He’s recalling the frustration of the other members of the Byrds when they discovered that they’d been replaced for the recording of “Mr Tambourine Man” by a group of session men, including Leon Russell and Hal Blaine. McGuinn himself was permitted to sing and play 12-string guitar on the track, which was completed in a couple of passes. He was the only Byrd on the record. A few months later, now established as one of the world’s biggest groups, the whole band were allowed into the studio to play on “Turn, Turn, Turn”. They needed 77 takes. Enough said.

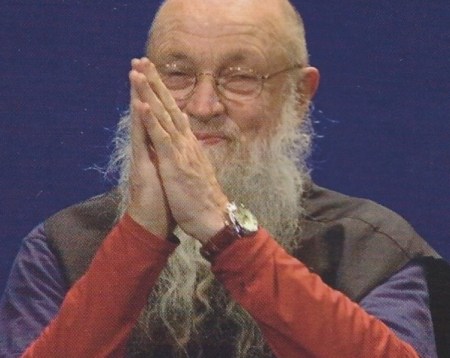

The film is a loving project, in every sense. The director is the son of the late Tommy Tedesco, whose guitar graced many of those hits (including Jack Nitzsche’s “The Lonely Surfer” and the Sandpipers’ “Guantanamera”), and whose presence gives the work its bookends. But there’s plenty of space for encounters with others, including Blaine, his fellow drummer Earl Palmer, the saxophonist Plas Johnson, the bass-guitarists Carol Kaye and Joe Osborn, the trombonist Lou McCreary, the percussionist Julius Wechter, the pianist Don Randi, the guitarists Bill Pitman, Glen Campbell and Al Casey, and many others, including the engineers Stan Ross and Larry Levine, as well as Brian Wilson, Herb Albert, Cher, Jimmy Webb and Lou Adler. The project was started by Denny Tedesco many years ago; several of his interviewees — including Palmer, McCreary, Wechter, Ross, Levine and Casey, as well as his father — have died since he filmed them.

Inevitably, there’s a touch too much boosterism. Hollywood isn’t the only place where the making of the great pop hits of the ’60s was facilitated by great session men. But these certainly were fantastic musicians, most of them jazz-trained but ready to dial down their chops to whatever the producer required, be it Phil Spector or Snuff Garrett. Once or twice you get a hint of less positive feelings about the tasks that were put before them, but there seems to have been a genuine enthusiasm for the imagination Brian Wilson brought with him into the studio — although, of course, Wilson’s sessions at the time of Pet Sounds and Smile tended to go on for weeks at a time, ensuring a steady revenue stream.

Wechter tells a fond story about Alpert, whose first Tijuana Brass session was not registered with the union, enabling him to pay the musicians below the standard rate, which was all he could afford. When “The Lonely Bull” became a massive hit, the first thing the trumpeter did was go round to the union, fill in the forms, and pay the musicians the full scale.

Somebody relates how, at the time of “These Boots Were Made for Walking”, Nancy Sinatra and her father were both appearing at separate Las Vegas venues. Irv Cottler, Frank Sinatra’s veteran drummer, discovered that Blaine, whose bass-drum fills had provided “Boots” with one of its hooks, was being paid $2,500 a week to leave the studio and back up Nancy on stage. He, Cottler, was making $700 a week.

The guys who spent their lives shuttling from Gold Star to Western to Capitol to Radio Recorders got rich in the process, which leads Blaine himself to tell the saddest story. The studio income from a career including 50 No 1 hits and six consecutive records of the year at the Grammy awards (including “Strangers in the Night”, “Up, Up, and Away” and “Mrs Robinson”) had brought him a mansion in Beverly Hills, a motor yacht and and a Rolls-Royce. They were all taken away by a divorce settlement that coincided with the ending of the boom time for session men. Out of music, he left Los Angeles and worked for a while at a menial job somewhere in Arizona. But then in 2000 he and Palmer, his mentor, were inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, and his life in music restarted.

Back in 2011 Blaine gave a great quote about the experience of listening to oldies stations to Marc Myers of the Wall Street Journal. “You hear your youth,” he told Myers. “I hear a day at the office or a divorce.” But that’s just a session man’s humour. The film is full of warmth and remembered pleasure, like the moment Carol Kaye shows us how she came up with the walking bass riff that made Sonny and Cher’s “The Beat Goes On” into a great record rather than just a decent song.

The Wrecking Crew was premiered at the South by Southwest festival in 2008 but a long campaign for Kickstarter funds was required in order to to pay the song licensing fees before it could be allowed out on a proper, if limited, release around the world (I saw it at the Art House cinema in Crouch End, North London). It’s not as polished a cinematic artefact as Standing in the Shadows of Motown or Muscle Shoals, but that’s part of its appeal. As an addition to the historical record, it’s priceless.