Many accents, one voice

Just about the first thing I discovered when I began a three-year term as artistic director of Berlin’s historic jazz festival in 2015 was that I would be required to explain myself. More specifically, I would be asked to describe my “concept”. This was a little disconcerting since I didn’t really have one, at least not in any worked-out form.

What I came up with, thinking on my feet, was a definition applicable to the kind of festival I wanted to make. “Jazz,” I told my inquisitors, “is any music that couldn’t exist if jazz hadn’t existed.”

I’ve never been quite sure whether I invented that aphorism simply out of expediency, in order to cover myself and to explain some of the music I wanted to present, in which the elements of traditional forms of jazz were sometimes attentuated or modified almost to invisibility. Eventually I decided that I believed it enough to feel comfortable about using it whenever it was necessary to justify something.

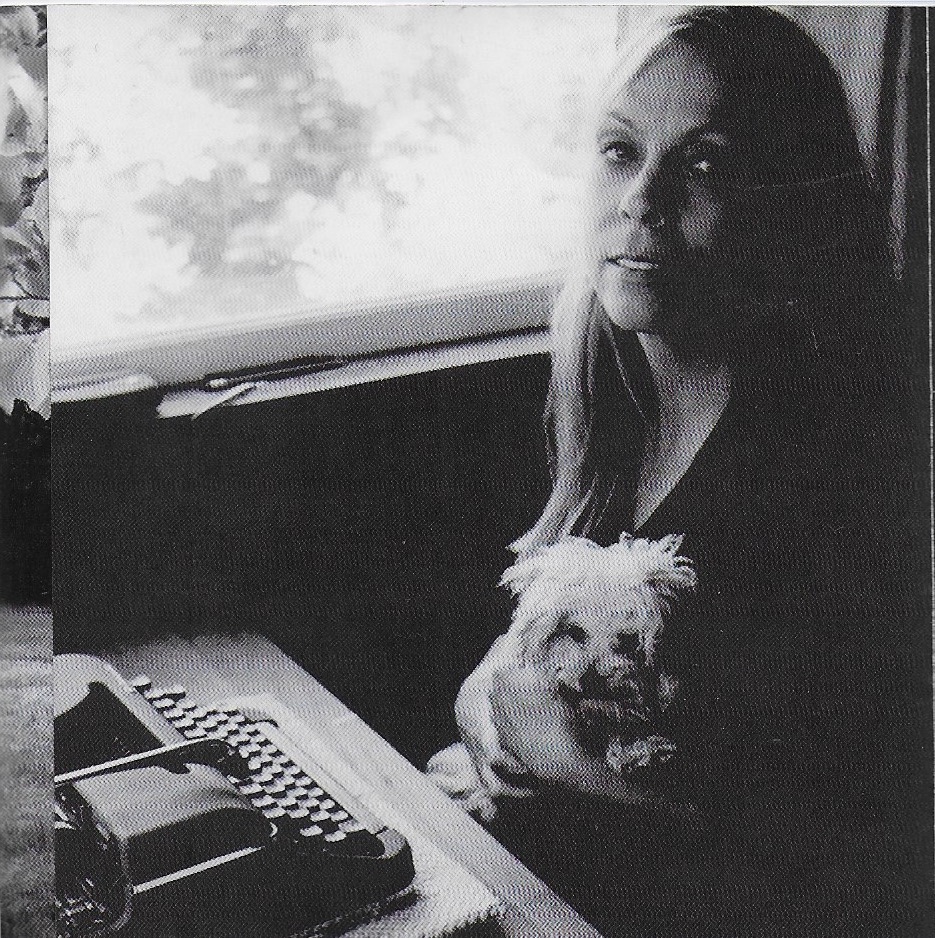

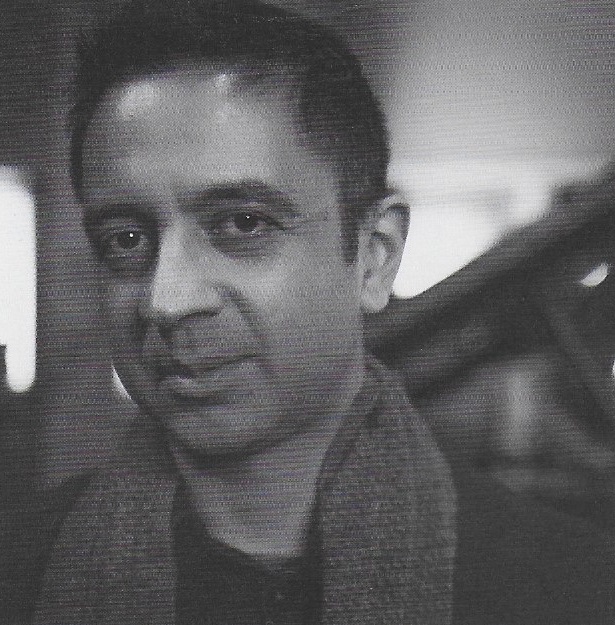

In my first year, the best example was provided by Divan of the Continents, a 22-piece band jointly led by Cymin Samawatie, a singer born in Berlin to Iranian parents, and Ketan Bhatti, a drummer born in India. Both graduates of jazz courses at Berlin’s University of the Arts (the UdK), together they had devised an ambitious project to bring together a large ensemble of locally based musicians from various ethnic backgrounds, from the principal viola-player of the Berlin Philharmonic and an English free-jazz trombonist to virtuosos of the sheng, the oud, the ney, the kanun and the koto. The aim was to work at creating music which honoured the essence of each player’s respective genre while (and this is the important bit) aiming for something genuinely new. What it would not be was an example of musical tourism. It wouldn’t be obviously “jazz”, either. But you could even see this as being a modern version of jazz’s origin story, in which elements of African and European musics came together to form a hybrid that took on a life of its own.

Since the music was complex, it seemed right to arrange for them to have three days of rehearsals in the small concert hall at the UdK’s Jazz Institute, open to students and the public. Then, on the festival’s closing night, they gave a performance in the 1,000-seater hall of the Berliner Festspiele, leading off a bill completed by Louis Moholo-Moholo’s Four Blokes and Ambrose Akinmusire’s quartet with the singer Theo Bleckmann. It was, I think, a success: the audience gave every appearance of being intrigued, particularly by the settings of poetry sung by Samawatie and two other female singers.

Now Samawatie and Bhatti have made an album of that music, and other pieces, with an ensemble of similar size and instrumentation, containing about half the original personnel. In the meantime, the project been retitled: the album is called Trickster Orchestra. But the concept is the same, and the time spent in preparation has resulted in something rather extraordinary: a music in which the sheng of Wu Wei and the viola of Martin Stegner have equal weight, in which the double bass of Ralf Schwarz can emerge with a walking 4/4 line and the various items of tuned percussion can set up rhythm patterns reminiscent of Steve Reich. The words of the songs range from Psalm 130 to the Sufi poet Rumi and the contemporary poet Efe Duvan, and are sung in Farsi, Hebrew, Arabic and Turkish. The lyricism is always poised and sometimes swooning, but the serenity can be punctured by a fusillade of drums, subtly coloured by electronics.

It’s not a mosaic, but it is a kaleidoscope. Each musician retains her or his own tuning and vocabulary. The various tones, textures and idiomatic accents are overlapped, juxtaposed and filtered through each other, creating something much more interesting than a flavourless fusion. I think it would have interested the founder of Berlin’s jazz festival, the late Joachim-Ernst Berendt, a man with a strong belief in the potential value of opening jazz up to new relationships with the music of other cultures. Trickster Orchestra is an impressive example of where that kind of thinking has led, giving musicians of high skill and inquiring minds the chance to find new paths.

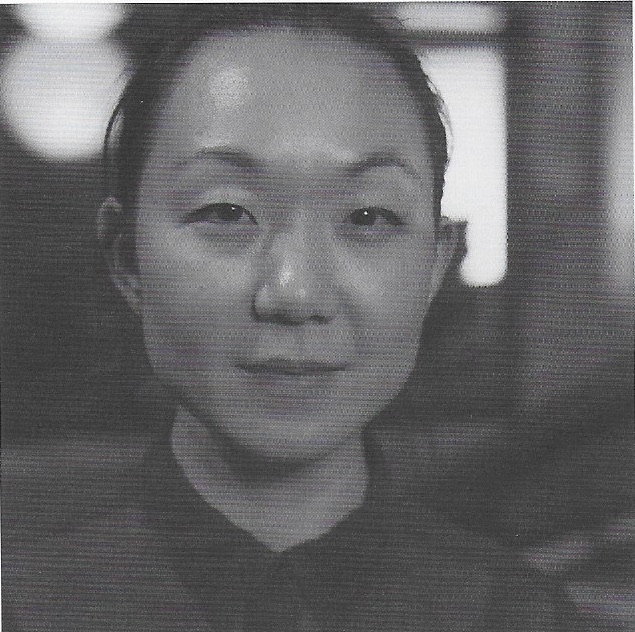

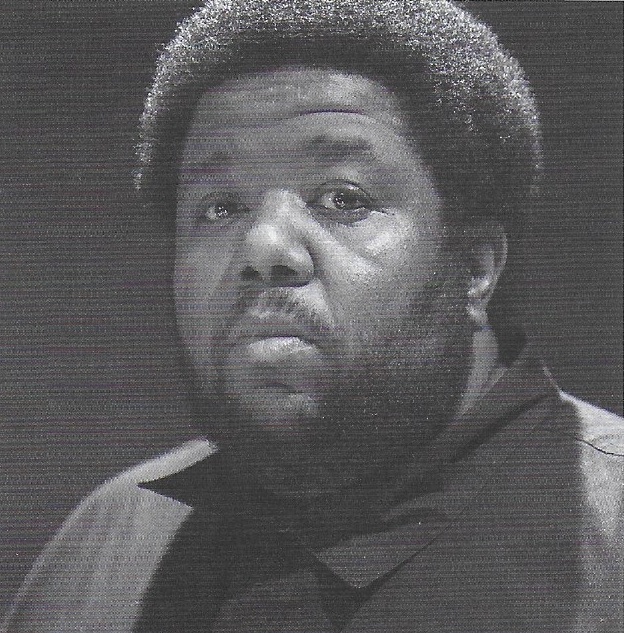

* Trickster Orchestra by Cymin Samawatie and Ketan Bhatti is out now on the ECM label. The photograph of Bassem Alhouri (kanun), Naoko Kikuchi (koto) and Ralf Schwarz (bass) is from their 2015 concert in Berlin and was taken by Camille Blake.