‘The Philosophy of Modern Song’

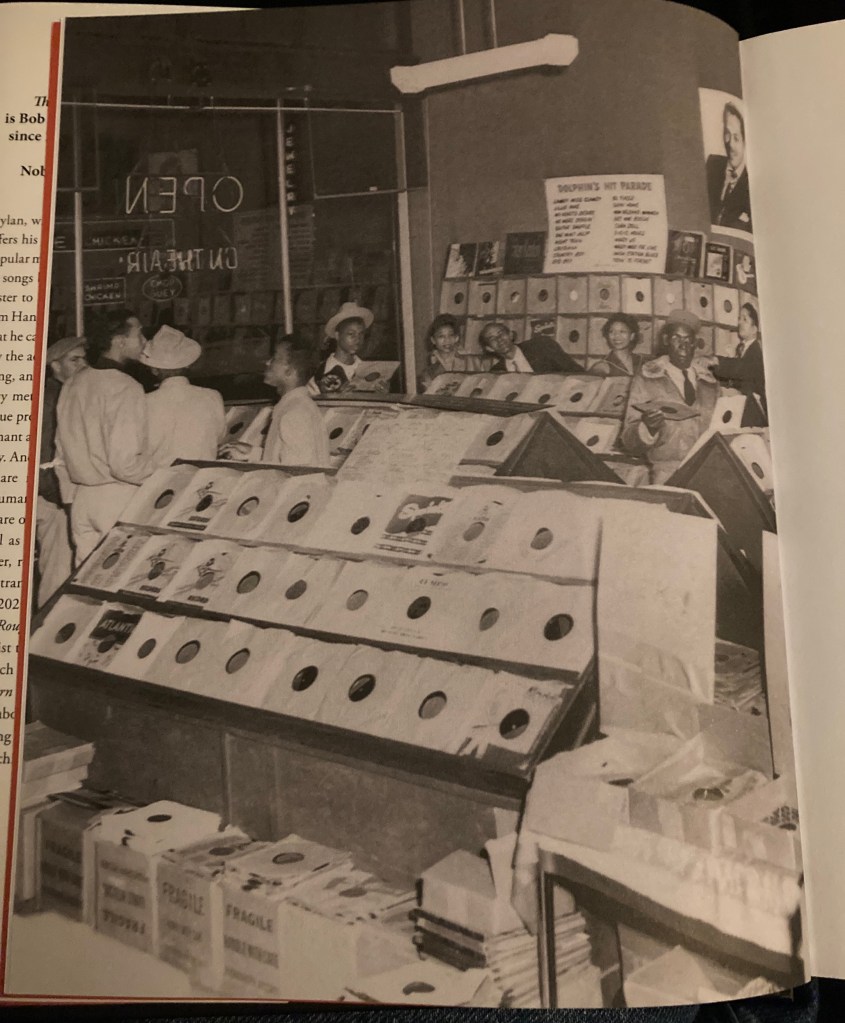

The second photograph you see when you open Bob Dylan’s The Philosophy of Modern Song is one of the reasons I don’t entirely resent having paid the £35 the book costs. It shows a group of customers in a record shop, surrounded by boxes and displays of 78rpm discs. There’s no caption, but there’s a clue in a poster on the wall saying “Dolphin’s Hit Parade”, followed by a list of songs. So this is Dolphin’s of Hollywood, the record shop opened by the black entrepreneur John Dolphin in South Central Los Angeles in 1948. Its frontage was on Vernon Avenue, near the corner with Central Avenue – the main stem of black LA in that era, thanks to nearby night spots like the Club Alabam, the Turban Room, the Downbeat, Elks Hall and Jack’s Basket Room. Dolphin’s opening hours — 24 hours a day, including Sundays — were pioneering, as was a buy-one-get-one-free deal. The titles on the poster — deciphered with the aid of a magnifying glass — tell you that this is the spring of 1952, which is when “Lawdy Miss Clawdy” by the Lloyd Price Orchestra was released on the Specialty label, along with “One Mint Julep” by the Clovers (Atlantic), “Night Train” by the saxophonist Jimmy Forrest (United) and “My Heart’s Desire” by the vocal duo Jimmie Lee and Artis with Jay Franks and his Rockets of Rhythm (Modern)*.

John Dolphin had originally tried to open a business in Hollywood, but was denied the opportunity on the grounds of his colour. So, locating instead in the heart of the black community, he gave the shop a semi-ironic title, soon adding a record label of his own, called Recorded in Hollywood, whose output included early recordings by the Hollywood Flames and Jesse Belvin. His business, and others in the neighborhood, were so successful that they began to attract white customers, which in turn brought threats from white competitors to such a degree that in 1954 he organised a protest against their campaign of intimidation. In 1958 he was shot dead in his office by a disappointed singer named Percy Ivy, in the presence of two soon-to-be-famous white teenagers, Sandy Nelson and Bruce Johnston, who had been trying to get him interested in their music. In the photograph, John Dolphin is the man in the dark suit under the picture of Billy Eckstine.

None of this information is to be found in the book, in which Dylan discusses 66 other songs. You’ve probably already read about it (I recommend Dwight Garner in the New York Times or Craig Brown in Private Eye), so I’m not going to try and review it properly. It’s easy to describe. Most of his choices get two chunks of prose: first, an outpouring of feelings and images provoked by the recording in question, followed by a historical note, all illustrated by a selection of images that range from the relevant to the tangential or allusive. Jimmy Reed’s “Big Boss Man”, for instance, gets a description of the boss class (“You’re the famous Chieftain, the enormous tight fisted penny pincher who treats all the workers like errand boys”) followed by a short description of Reed’s music (“You put him with Jimmie Rodgers and Thelonious Monk, two other musicians whose work never sounds crowded no matter how many players are there” and “He plays the harmonica through a neck rack. And you can’t do much with a harmonica in a neck rack” — really? Bob should go back and listen to his own live recordings from 1965 and ’66. Or maybe he’s putting us on). There are pictures of Reed, of Brando in The Godfather, and Elvis Presley — unmentioned in the text — with Colonel Tom Parker, who is pretending to play an acoustic 12-string guitar and is presumably there to represent boss men in general.

The criteria by which Dylan chose the songs are never made clear. Many are from his childhood in the pre-rock era. Others seem to have been plucked at random. As many have already pointed out, in some bafflement, only a tiny handful are by women. But the specifics don’t seem to be important: they are there to give Dylan the chance to vent. Where people with synaesthesia experience music as colour, Dylan seems to experience a song as a set of feelings that may or may not be triggered by anything explicit in the song itself, arising instead from his own imagination, his memories, fears, fantasies. Or perhaps that’s quite wrong. Perhaps he’s just making it up, and why not? At any rate, while working your way through one laboured exegesis after another, you may find yourself thinking that he’d be better employed fashioning them into songs of his own.

Soon after I started reading The Philosophy of Modern Song, I found I wasn’t enjoying it very much. It isn’t anywhere near the standard of his brilliant sleeve note for World Gone Wrong in 1993 or the considered thoughts on music expressed in several interviews in recent years. It didn’t seem to be telling me anything original or important. As for a “philosophy of modern song”, the closest he gets to that is his claim that a song’s true value resides in the listener’s response to it, which I guess is the book’s raison d’être, or at least its excuse. So I thought I’d try it from another angle. On the basis of having loved his Theme Time Radio Hour programmes largely because of the sound of his voice, I spent another few quid on the audiobook, only to discover that most of the reading is done by famous actors, from Jeff Bridges to Sissy Spacek. Why would I want to hear that? When Dylan does appear, his voice sounds weirdly remote, losing all the warmth and intimacy of the radio series. And there are times, to be blunt, when he sounds like he’s reading someone else’s research. So I’ve given up on that, too, at least for now.

Whatever the contentious origins of its component parts, Chronicles Vol 1 was a proper book, the product of craft and concentration. Which The Philosophy of Modern Song definitely isn’t. It’s inessential, a coffee-table book to be given as a Christmas present. Clearly he didn’t fancy writing Chronicles Vol 2 — perhaps, who can tell, because he knows that’s what we want.

* Correction: In the original post, “My Heart’s Desire” was credited to the Wheels, whose recording was not released until 1956. The recording by Jimmie Lee and Artis was released on the LA-based Modern label in early 1952.

* Bob Dylan’s The Philosophy of Modern Song is published by Simon & Schuster. The audio version is available from audible.co.uk. The copyright in the photograph above is owned by the Michael Ochs Archive via Getty Images.