2025: The best bits

The brutish reality of Donald Trump’s second term as president of the United States was beginning to emerge when Bruce Springsteen arrived for the first date of his 2025 European tour in Manchester on May 14. I wasn’t there, which meant I didn’t hear him perform, as his final encore, Bob Dylan’s “Chimes of Freedom”, a song that could be seen as the last, magnificent expression of its creator’s 1963-64 incarnation as a singer of protest ballads. The clip above shows that Springsteen, seeking to take a stand at another moment in history, gave it everything he had. In October, Al Stewart made a similarly fine choice when, during his farewell tour, he closed his London Palladium show with Dylan’s “Love Minus Zero/No Limit”, one of the compositions that had shaped his own career as a songwriter. With proper humility, but with their own creative spirit still demonstrably alive and alert, Springsteen and Stewart were reminding us of the enduring significance of the greatest artist of our time, whose own emergence was explored in the finest archival release of the year.

NEW ALBUMS

1 Ambrose Akinmusire: Honey From a Winter Stone (Nonesuch)

2 Mavis Staples: Sad and Beautiful World (Anti-)

3 Arve Henriksen / Trygve Seim / Anders Jormin / Markku Ouaskari: Arcanum (ECM)

4 Masabumi Kikuchi: Hanamichi / The Final Studio Recording Vol II (Red Hook)

5 The Necks: Disquiet (Northern Spy)

6 Patricia Brennan: Of the Near and Far (Pyroclastic)

7 Amina Claudine Myers: Solace of the Mind (Red Hook)

8 The Waterboys: Life, Death and Dennis Hopper (Sun)

9 Peter Brötzmann: The Quartet (Okoroku)

10 Chris Ingham Quintet: Walter / Donald (Downhome)

11 Vilhelm Bromander Unfolding Orchestra: Jorden Vi Ärvde (Thanatosis)

12 Nels Cline: Consentrik Quartet (Blue Note)

13 Bryan Ferry & Amelia Barratt: Loose Talk (Dene Jesmond)

14 Lucy Railton: Blue Veil (Ideologic Organ)

15 Charles Lloyd: Figures in Blue (Blue Note)

REISSUE / ARCHIVE

1 Bob Dylan: Through the Open Window: The Bootleg Series Vol 18 1956-1963 (Columbia Legacy)

2 Charlie Parker: Bird in Kansas City (Verve)

3 Dionne Warwick: Make It Easy on Yourself — The Scepter Recordings 1962-1971 (SoulMusic)

4 Mike Westbrook Orchestra: The Cortège / Live at the BBC 1980 (Cadillac)

5 Pharoah Sanders: Izipho Zam (Strata East)

6 Tomasz Stanko Quartet: September Night (ECM)

7 Larry Stabbins, Keith Tippett, Louis Moholo-Moholo: Live in Foggia (Ogun)

8 A New Awakening: Adventures in British Jazz 1966-1971 (Strawberry)

9 Emahoy Tsege Mariam Gebru: Church of Kidane Mehret (Mississippi)

10 Irma Thomas: Wish Someone Would Care (Kent)

LIVE PERFORMANCE

1 The Weather Station (Islington Town Hall, March)

2 Tyshawn Sorey Trio (Cafe Oto, February)

3 Paul Brady (Bush Hall, April)

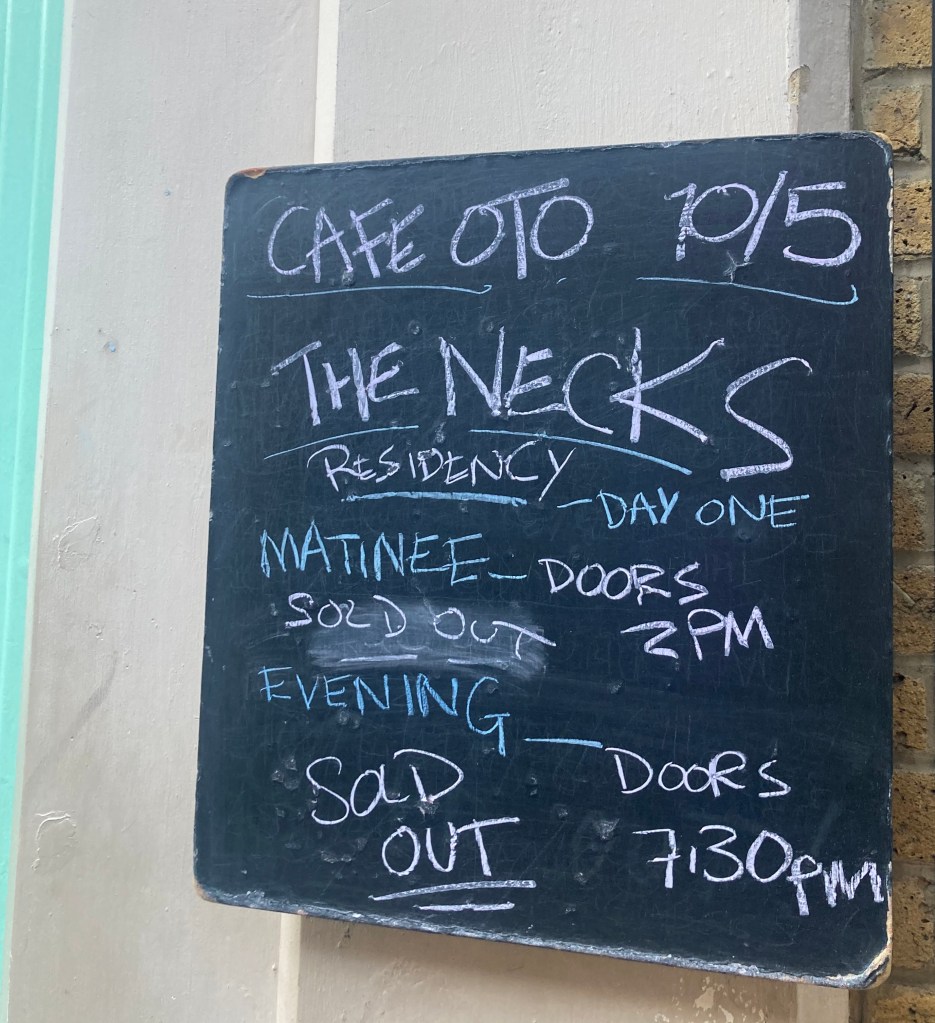

4 The Necks (Cafe Oto, May)

5 Maria Schneider / Oslo Jazz Ensemble (Barbican, March)

6 Tom Skinner (Queen Elizabeth Hall, November)

7 Patti Smith Plays Horses (London Palladium, October)

8 Schlippenbach Trio (Cafe Oto, Jan)

9 Bang on a Can All Stars: Terry Riley 80th birthday tribute (Barbican, May)

10 Wadada Leo Smith / Vijay Iyer (Wigmore Hall, October)

11 Olie Brice Quartet (Vortex, July)

12 Adrian Dunbar / Guildhall Sessions Orchestra: The Waste Land (Queen Elizabeth Hall, November)

13 Al Stewart (London Palladium, October)

14 Sebastian Rochford’s Finding Ways (Jazz in the Round, Cockpit Theatre, November)

15 Louis Moholo-Moholo Memorial (100 Club, August)

MUSIC BOOKS

1 Billy Hart w/Ethan Iverson: Oceans of Time (Cymbal Press)

2 Tom Piazza: Living in the Present with John Prine (Omnibus)

3 Jonathan Gould: Burning Down the House (Mariner Books)

4. Neil Storey (ed.): The Island Book of Records Vol 2, 1969-70 (Manchester University Press)

5 Sonny Simmons w/Marc Chaloin: Before You Die Later (Blank Forms)

FICTION

1 Vincenzo Latronico: Perfection (Fitzcarraldo)

2 Sam Sussman: Boy from the North Country (Grove Press)

3 Andrew Miller: The Land in Winter (Sceptre)

NON-FICTION

Paul Gorman: Granny Takes a Trip (White Rabbit)

FILMS

1 Nickel Boys (dir. RaMell Ross)

2 From Hilde, With Love (dir. Andreas Dresen)

3 Sinners (dir. Ryan Coogler)

4 The Ballad of Wallis Island (dir. James Griffiths)

5 A Complete Unknown (dir. James Mangold)

DANCE

Quadrophenia: A Mod Ballet (Sadler’s Wells, July)

EXHIBITIONS

1 Noah Davis (Barbican, May)

2 Jean-François Millet (National Gallery, October)

3 Lee Miller (Tate Britain, December)