Rougher and rowdier (take 1)

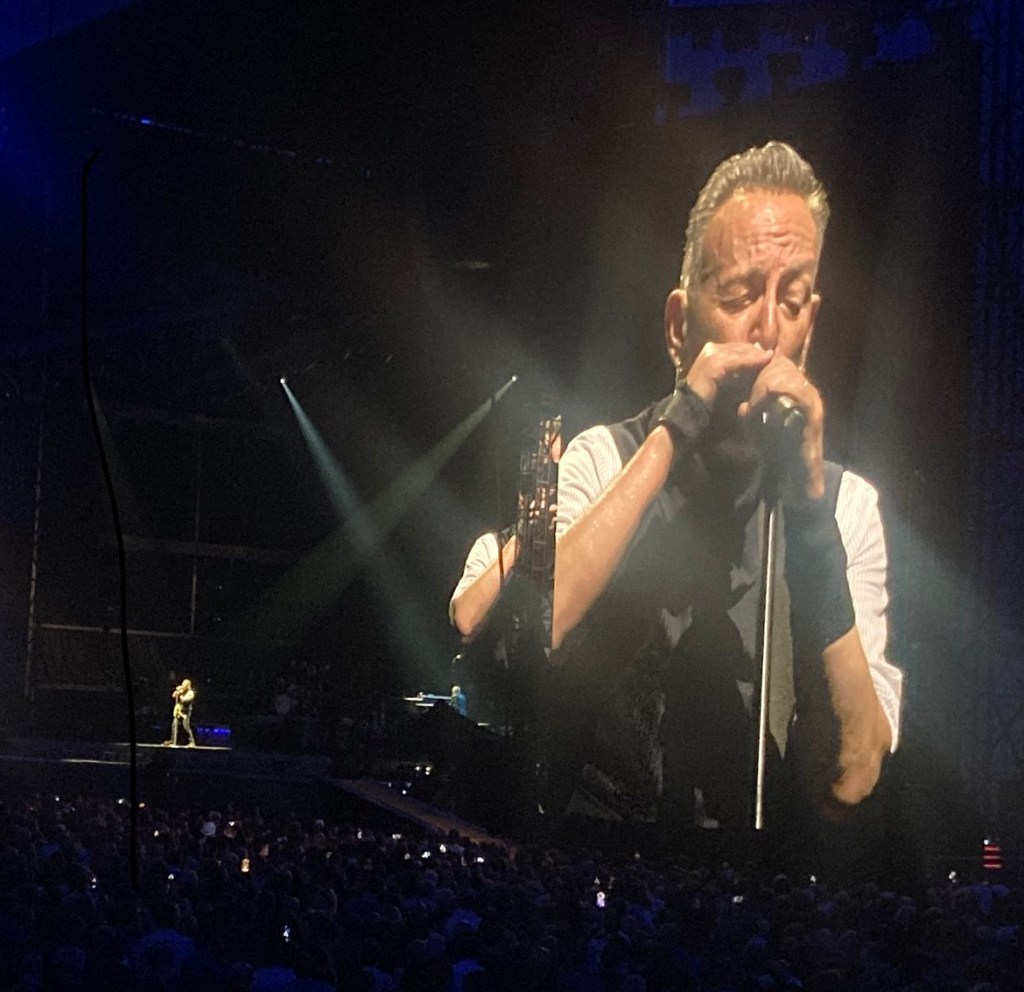

Almost as soon as Bob Dylan and his musicians emerged on to the half-darkened stage of the Motorpoint Arena last night, a jangle of discordant electric guitars made me uneasy. It turned out that the discordance was chiefly coming from the guitar of Dylan himself, who was already sitting at his piano bench, with his back turned to the audience. Within a few seconds that jangle had somehow formed itself into the opening of “All Along the Watchtower”, the first of the 17 songs — nine of them from Rough and Rowdy Ways — he’d give us.

For me, it was a strange concert from several perspectives. It was certainly far from the poised, concentrated, finely detailed performance he’d presented at the same venue in Nottingham two years earlier, which had been a measurable level up even from the two fine shows I’d seen him give at the London Palladium a week before that. Quite often I found myself thinking we were back in the ’90s, when the thing I seemed to say most frequently after one of his concerts, while defending him to sceptics, was, “Well, they’re his songs, he can do what he likes with them.”

Another early warning sign: he repeated the first verse of “Watchtower”, meaning that the song no longer ended with “Two riders were approaching / The wind began to howl” — among the most effective closing lines in popular music — but with “None of us along the line / Know what any of it is worth.” I have no better idea of why he’d choose to do that than of why he’d rearrange a full-band version of “Desolation Row” to the galloping tom-tom beat of “Johnny, Remember Me” or decide to extend the same song with a meaningless piano solo.

The sound was much worse than two years earlier in the same hall. It was louder and harsher, and yet somehow less powerful, and with a much more distracting echo on the voice. Sometimes I flinched involuntarily when he put exaggerated emphasis on a particular syllable, as he so often does. The harmonica, which appeared on several songs, had mislaid its customary poignancy and what he played on it was, unusually, not particularly interesting, even on the closing “Every Grain of Sand”.

His current modus operandi is to start many songs — “I’ve Made Up My Mind to Give Myself to You”, for instance — standing near the back of the stage, singing into a handheld microphone. After a verse or two he advances to the baby grand piano, leans over it, and sings another verse or two, reading from the book of lyrics resting on top of the instrument. So far, so good. But then he sits down and clogs up the music by adding his wilful and often wayward piano-playing to the guitar interplay of Bob Britt and Doug Lancio. There’s no finesse in his keyboard contribution this time round, which is another contrast with 2022. It’s a form of interference, which of course may be what he’s after.

“My Own Version of You” closed with a chaotic ending that suggested that this was the first time they’d played it, rather than the two-hundred-and-twenty-somethingth. “To Be Alone With You” was such a mess that I couldn’t help thinking, “What on earth does he imagine he’s doing?” The drumming of “the great Jim Keltner” — as Dylan quite justifiably introduced him — never seemed as well integrated into the band as that of his precedessor in 2022, Charley Drayton, or George Receli from further back.

During the boogie of “Watching the River Flow” it was tempting to conclude rather irritably that the Shadow Blasters, Dylan’s first band, probably sounded better doing something similar at the Hibbing High School talent contest in 1957. For the first time in 59 years of going to see him on a fairly regular basis, I felt that I could have left my seat, gone to buy a beer, and returned without having missed anything important.

Of course that’s not true. There were moments of grace, mostly when the instrumentation was reduced to voice and piano, as in “Key West”, or voice and guitars, as in “Mother of Muses”. The first two verses of “Made Up My Mind” were lovely, as were the out of tempo bits of “It’s All Over Now, Baby Blue”, delivered against Tony Garnier’s bowed bass. By the time Dylan got to “Goodbye Jimmy Reed”, the penultimate item on the set list, he was singing beautifully, with clarity and marvellous timing.

Every time you see him now, you think it might be the last. So this one wasn’t great. But that doesn’t really matter, even if there aren’t any more. Time past, time present: lucky to have it at all, all of it.