Aces high in Camden Town

On the first floor at the Hawley Arms, a pub in Camden Town, Ted Carroll is spinning the discs. He’s started the session with the Bobbettes’ “Mr Lee”, a record that changed his life when he bought an original copy on the London label. He’ll go on to play Bo Diddley’s “Bo Diddley”, Inez and Charlie Foxx’s “Mockingbird” and other choice stuff before resuming his conversations with guests at last night’s 50th birthday celebration for Ace Records, which he and his co-founders, Roger Armstrong and Trevor Churchill, turned into the most prolific and consistently rewarding of reissue labels.

I used to visit Ted’s stall at the back of 93 Golborne Road, up at the then-untrendy north end of Portobello Road, soon after he opened it in 1971 with a stock built around 1,800 London 45s from the ’50s and ’60s. The equivalent of New York’s Village Oldies and House of Oldies, it attracted a clientele of people — some of them famous — looking for rare old R&B, rock and roll and doo-wop vinyl. He added a stall in Soho later in the decade before opening the Rock On shop on Kentish Town Road, next door to Camden Town tube station, from where he also ran the Chiswick label.

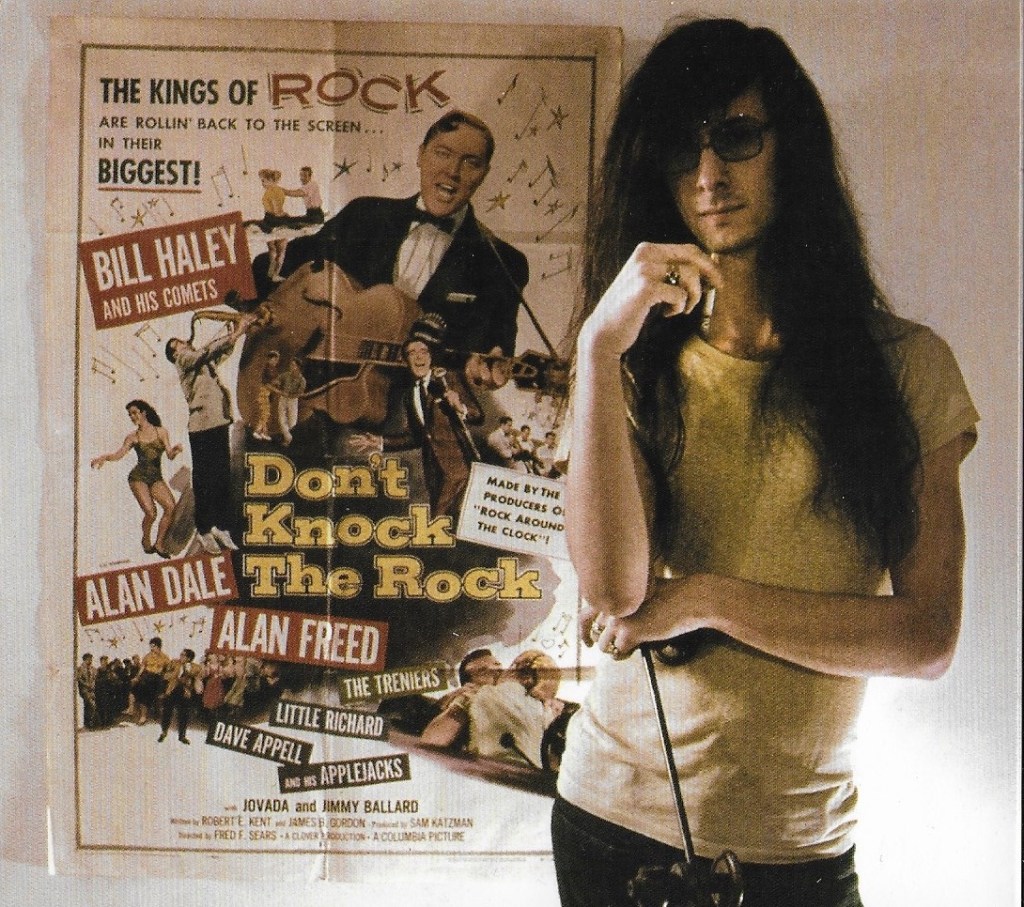

Ace began with the acquisition of Johnny Vincent’s label of the same name, out of Jackson, Mississippi. That was the first of many such deals made with some of the great American post-war record men, including Art Rupe of Specialty, Hy Weiss of Old Town and the Bihari brothers of Modern, a species now extinct. Carroll, Armstrong and Churchill had set off on their mission of creating high-class reissues of neglected music, assembled with love, care, and thousands of hours spent in tape vaults across the US. Among later additions would be the Fantasy group of labels, which included Stax/Volt, thus enabling Armstrong, as he told me last night, to stumble open-mouthed upon the session tapes of “Sitting on the Dock of the Bay”.

Personally, I’m profoundly grateful to such compilers as Mick Patrick, Ady Croasdell, Tony Rounce, John Broven, Dean Rudland and Alec Palao for the enthusiasm and scholarship behind dozens of wonderful CDs devoted to stuff I care about. There’s the imaginatively programmed songwriters’ and producers’ series, covering the works of Goffin & King, Leiber & Stoller, Greenwich & Barry, Mann & Weil, Jackie DeShannon, Randy Newman, Laura Nyro, P. F. Sloan & Steve Barri, Bob Gaudio, Dan Penn & Spooner Oldham, Bert Berns, Jerry Ragovoy, and others. There’s the four-volume Sue story, put together by Rob Finnis, and the epic five discs of the late Dave Godin’s Deep Soul Treasures. There’s Ady Croasdell’s beautiful Lou Johnson anthology, his two-volume This Is Lowrider Soul, and his compilation of Doré label tracks called L. A. Soul Sides, including Rita and the Tiaras’ magical “Gone With the Wind Is My Love”. There’s Mick Patrick’s collection of Teddy Randazzo’s great productions and, going back to 1984, Where the Girls Are, his first compilation and one of many devoted to the beloved girl-group genre.

That’s just scratching the surface. And whether pop, blues, R&B, Northern Soul, funk, gospel or jazz, the packaging of Ace’s releases has always been exemplary, thanks to the informative and enjoyable annotations and picture research by the compilers, and to intelligent artwork by designers including Neil Dell, who worked on many of the CDs I’ve mentioned.

The label was sold a couple of years ago. Its new owners, a Swedish company called Cosmos Music, seem committed to continuing on the same path, with the same managers and contributors. A lot of them were at last night’s very convivial party, which started well for me when I walked in to the sound of Dean Rudland playing Oscar Brown Jr’s “Work Song” off a French EP, followed by Ray Charles giving the Raelettes’ Margie Hendrix her finest hour — well, 16 bars — on “You Are My Sunshine”.

Ted, who followed Dean on the decks, now runs a new incarnation of Rock On in the lovely market town of Stamford in Lincolnshire, just off the A1; a bit different from Camden Town — where, as I walked back to the tube, a trio called Thistle were trying to convince their audience that the ground-floor room of the Elephants Head pub was CBGB, this was 1975, and the next band on the bill would be the Patti Smith Group.

Fifty years ago Ted, Roger, Trevor and their helpers did a great thing by starting Ace. When a label introduces you to such gems as Margaret Mandolph’s ” I Wanna Make You Happy” (on Croasdell’s Tears in My Eyes compilation from 1985) and the Vogues’ “Magic Town” (on Glitter and Gold, the first of Patrick’s two Mann & Weil CDs), you can only raise a glass to the work they’ve done and thank them for the happiness it continues to bring.