Hello (and goodbye), Jimmy Reed

Half a century after his death at the age of 50, the great bluesman Jimmy Reed turned up yesterday in the New York Times obituaries section. The NYT has an excellent habit of memorialising, under the rubric ‘Overlooked’, people who weren’t seemed worthy of inclusion at the time of their death. Nice to see Reed getting his due, however belated.

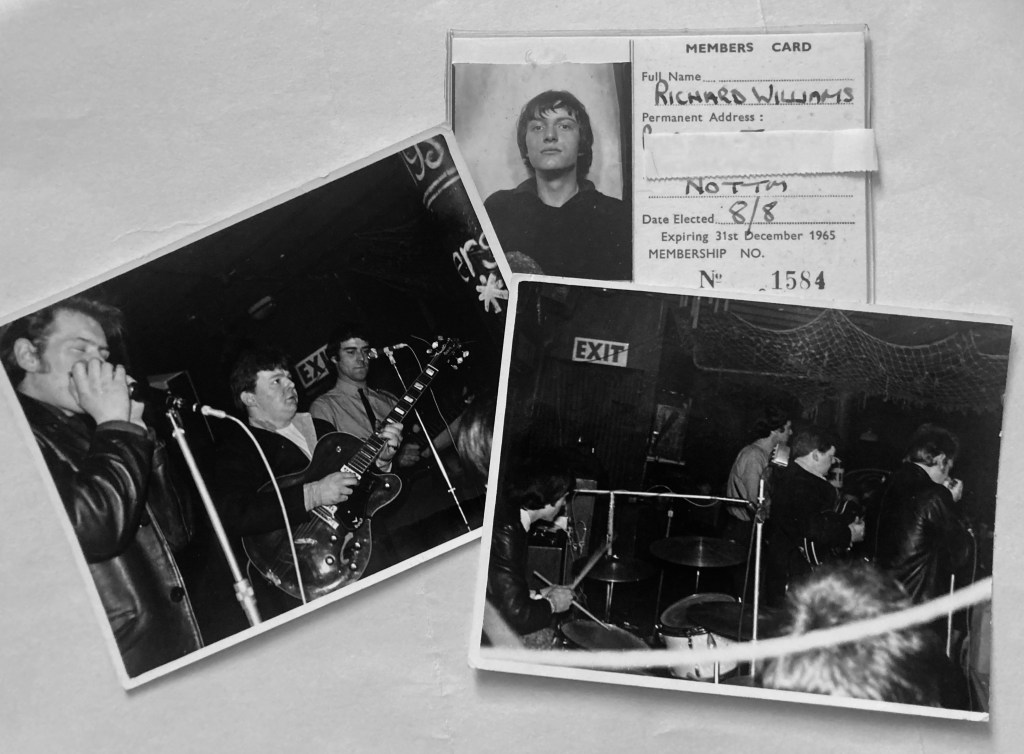

While he’s not forgotten today, his influence is certainly underrated. The records he cut in Chicago for the Vee-Jay label between 1953 and 1965 were the ones that white British teenagers hoping to become musicians were most likely to start off by studying and copying in the early ’60s. Their rudimentary nature made them the easiest first lessons in the language of the blues.

The tempo of the basic shuffle didn’t vary much, usually from a slow-medium slouch to a medium lope. The characteristic twist to the basic blues chords was extremely powerful but straightforward and easy for a beginner to learn. This was what a young guitarist would master before feeling confident enough to tackle Chuck Berry’s intros or Elmore James’s slide figures. Reed’s harmonica style, with its long, high held notes, was relatively easy to imitate, as was the engaging mushmouth vocal style in which he sang his simple but compelling songs: “Hush Hush”, “Big Boss Man”, “Shame Shame Shame” and the rest. For British kids, it was like sitting the 11-plus exam: the entrance to a world of possibilities.

Reed liked having his own rhythm guitar supported by those of his friends, particularly Eddie Taylor and Lefty Bates. Somehow they never fell over each other. Sometimes there was a bass player (the young Curtis Mayfield played bass on a handful of sides in 1959) and always a drummer, first Earl Phillips and then Al Duncan, who also knew how to stay out of the way. Nowadays we can smile fondly when the beat gets turned around or Reed comes in a bar early, and yet still the record was deemed fit for release.

With those materials, Reed won the allegiance of a generation. His records were covered by those who were on their way to fame via the adopted medium of R&B — the Stones with “Honest I Do”, the Yardbirds with “I Ain’t Got You”, Them with “Baby What You Want Me to Do”, the Animals with “”Bright Lights, Big City”, the Grateful Dead with “Big Boss Man”, the Steve Miller Band with “You’re So Fine”. And the covers continued to proliferate, from Elvis Presley’s “Big Boss Man” in 1967 through Aretha Franklin’s “Honest I Do” in 1970 to Boz Scaggs’ “Down in Virginia” in 2018. And on his most recent album, Rough and Rowdy Ways, Bob Dylan recorded a new song called “Goodbye Jimmy Reed”, which has since become a regular part of his concert repertoire.

About 20 years ago I put together a proposal for a book about Reed. I’d read that he was broke when he died, and I started asking myself where all the money had gone. He’d written almost all of his hits, sold a lot of records, and seen his songs included on big-selling albums by other artists. Over the years, that would have been a great deal of money, very little of which made his way to him before his death after an epileptic attack in 1976.

I had in mind to do some serious research into what happened to his publishing copyrights — how many hands they had passed through, and who were the people, probably sitting behind large desks in Midtown Manhattan office blocks, who really made the money from them. That way I could tell the story behind the remark once made by the R&B singer Ruth Brown, who said of Ahmet Ertegun, the boss of her record company, that “for every Picasso on his wall, I had a damp stain on mine.”

I was going to call the book Meet Me in Your Home Town, after one of my favourite Reed songs. It was a reference to the way a sharecropper’s son from rural Mississippi, one of 10 children, had escaped plantation life, finding his way to Chicago and thence into the world of teenagers in just about every town in Britain, among whose number I included myself.

Sadly, the book never got written. Something else got in the way. But I’m pleased to see him being remembered in the columns of the New York Times, in an obit with which I have only one quibble. The author suggests that Reed’s delivery was “not as mesmerising, for example, as the reverberating braggadocio of Muddy Waters or the otherworldly moaning of Howlin’ Wolf.” Oh, dear writer, mesmerising is exactly what Jimmy Reed was. And still is.

* All Jimmy Reed’s Vee-Jay recordings were collected by Charly Records in 1994 in a six-CD set titled The Vee-Jay Years.