Autumn books 1: Joe Boyd

“Tango comes from the mud,” Brian Eno told an audience at Foyle’s bookshop the other night. He was conducting a public conversation with the author of And the Roots of Rhythm Remain, an 850-page examination of the forms of popular music with which Joe Boyd has engaged in Cuba, Jamaica, Brazil, Argentina, Bulgaria, Senegal, Albania and elsewhere during his six decades as a successful record producer and enlightened facilitator of musical projects.

For many years now it’s been rumoured that Boyd was writing a history of “world music”, a tale perhaps beginning with his presence at the famous meeting at a London pub in 1987 during which that rubric was invented, with the best of intentions and outcomes, as a way of persuading open-minded listeners to pay as much attention to music from other cultures as they did to their own western idioms. The result is much more interesting than a simple history; its eventual subtitle, “A Journey through Global Music”, conveys a much more accurate impression of what Boyd has taken on.

The quote about tango coming from the mud is to be found on page 483, where it’s identified as an Argentine saying. It was clever of Eno to spot it, because it says something larger about pretty much all the music Boyd considers here. How and when it happened, who made it happen, and to whom it happened are all part of his investigations, whether the music under consideration is Tropicália or townships jazz, Django Reinhardt or Béla Bartók.

I’m still working my way through the book, which will take a while even though Boyd writes in the easy, fluent, open-minded, anecdotal style familiar from White Bicycles, the relatively slender book about his adventures in the ’60s underground, published in 2005 to justified acclaim. Vast as his new one might seem, it’s worth reading with full attention, lest you miss some vital socio-cultural connection or valuable information on the roles played by, for example, the Ghanaian drummer Tony Allen, the Sudanese oud-player Abdel Aziz El Mubarak, Rodney Neyra of Havana’s Tropicana nightclub or the ballet impresario Sergei Diaghilev. (I didn’t know, for instance, that, according to Boyd, the names samba, rumba, mambo, tango and cha-cha all have their roots in Ki-Kongo, one of the languages of the Kongo people living in what are now the Republic of Congo, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Angola and Gabon.) Boyd’s enviable skill is to bring the reader an astonishing level of historical detail while wearing his research lightly and enlivening the narrative with exactly the right seasoning of his own views.

After buying the book at the Foyle’s event and getting it signed, I took it home and went straight to the chapter about tango. I like tango very much, although I once spent an evening in a bar in San Telmo, a Buenos Aires quarter then about to make the jump from funky to gentrified, proving to everyone’s satisfaction that I’ll never be able to dance it. I share Boyd’s enthusiasm for the singer Carlos Gardel to such an extent that I once visited the great man’s tomb in the cemetery of Chacarita in Buenos Aires, observing the ritual of leaving flowers at the base of his statue and placing a lit cigarette in the space left by the sculptor between the index and middle fingers of his raised right hand, because that’s how Gardel always sang until his untimely death in an air crash in 1935.

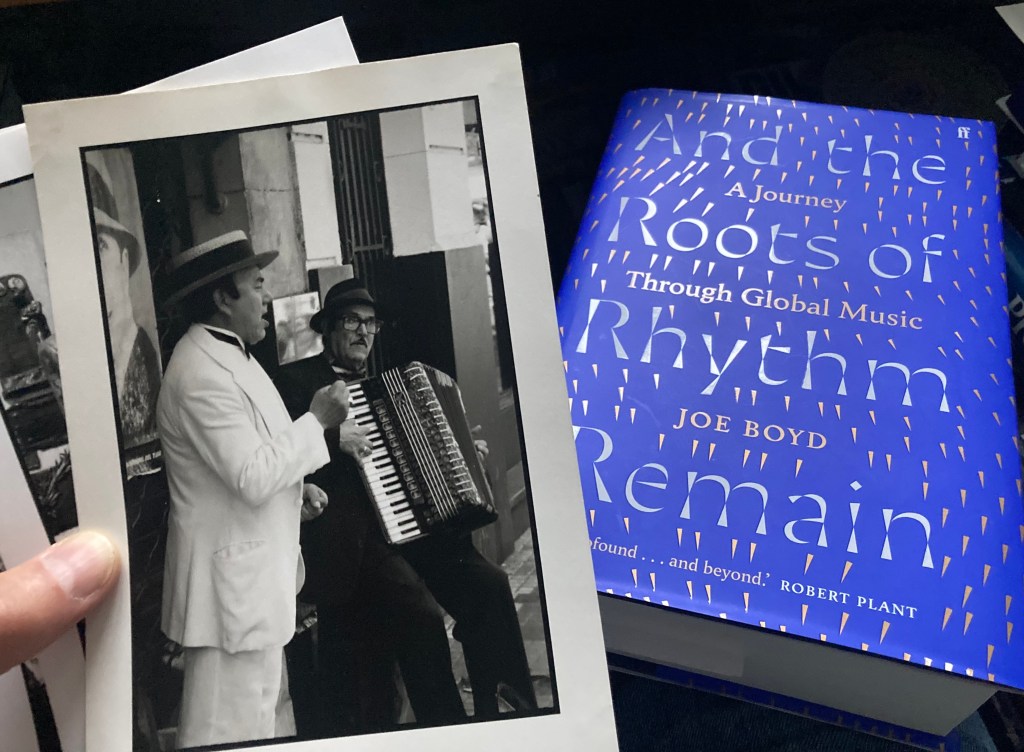

The photo above is one I took in 1994 on a sidewalk in Rosario, Argentina’s third largest city, the birthplace of Che Guevara and Lionel Messi. I was struck by the elegance and dignity of the street singer and his accordionist, who were serenading appreciative shoppers and other passers-by with a selection of songs made famous by Gardel.

Boyd traces the idiom’s origins in the bars and bordellos of Buenos Aires, examining its sources and tracking its destiny. He doesn’t share my fondness for the late composer and bandoneon virtuoso Astor Piazzolla, who became, he believes, “for tango what John Lewis and the MJQ were to jazz, ‘elevating’ it from the dancefloor and giving it concert-hall respectability.” He’s both right (in the comparison) and wrong (in the implicit criticism). Nobody who went, as I did, to see Piazzolla and his astonishing quintet for three out of their five nights in the intimate environment of the Almeida Theatre in London during the summer of 1985 could accuse them of forfeiting the sensual charms of tango in a pursuit of respectability. For a lot of worthwhile music with roots “in the mud”, the need to get people dancing is no longer a priority. But it’s a good and worthwhile argument to have, and I expect there’ll be many more as I work my way through what is shaping up to be not just an exceptionally enjoyable book but perhaps also an important one.

* Joe Boyd’s And the Roots of Rhythm Remain: A Journey Through Global Music is published by Faber & Faber (£30)