A Soho creative

Tot Taylor has an interesting history. Back in the mid-’80s, from an office near Oxford Circus, his Compact Organisation threatened to become to the London pop scene what Brooklyn’s Daptone outfit would be to R&B in the next century: a clever, occasionally brilliant re-imagining of past euphoria, creating music that could sometimes rival the sounds from which it took its inspiration. Compact’s founders, Tot Taylor and Paul Kinder, released records by Mari Wilson, Virna Lindt and Cynthia Scott that recalled the great days of the ’60s girl groups, while “The Beautiful Americans”, the sole 45 released by a non-existent group called the Beautiful Americans, evoked the early Walker Brothers in their semi-operatic prime.

Then Taylor and Kinder went their separate ways, the former diversifying his career. He composed music for film, TV and theatre (including the eight-hour Picasso’s Women for the National Theatre). From 2004-19 he co-ran a cutting-edge Soho art gallery called Riflemaker (after the business that had once occupied the premises on Beak Street). And in 2017 he published a 900-page novel titled The Story of John Nightly, a kind of Carnaby Street War and Peace, set amid the Swinging London music scene, its protagonist a pop star called “the most beautiful man in England” by the Sunday Times. And then he started making records again.

A confession: although I was sent an early proof copy of The Story of John Nightly, I haven’t read it properly. But I extracted it from the unread pile the other day. The reason is that I’ve been listening to his last two albums, Frisbee (2021) and Studio Sounds (2023), and falling for them to the extent that I’ve started thinking that if a bloke capable of this music has written a novel, it’s probably going to be worth reading.

Taylor makes records with a (sometimes deceptive) air of light-hearted whimsy and a deft, flexible craftsmanship that seem to have disappeared from contemporary pop music, overwhelmed by the prevailing modes of communal ecstasy and personal trauma. Crudely, you could place what he does somewhere between the Beatles of 1965-66 and the Beach Boys of Sunflower, maybe the last evolutionary step in songwriting terms before the art-rock of Kevin Ayers and Syd Barrett, but nothing he does sounds dated.

Every song has to have its own subject, shape and mood, just like a Beatles album. The humour is wry, never far away in things like “This Boy’s Hair” and “Vanity Flares”, both from the new album, on which he sings in his light, pleasant voice while playing pretty much everything except for drums (Shawn Lee), some of the guitars (Paul Cuddeford and Lewis Durham) and harp (Alina Brhezhinska).

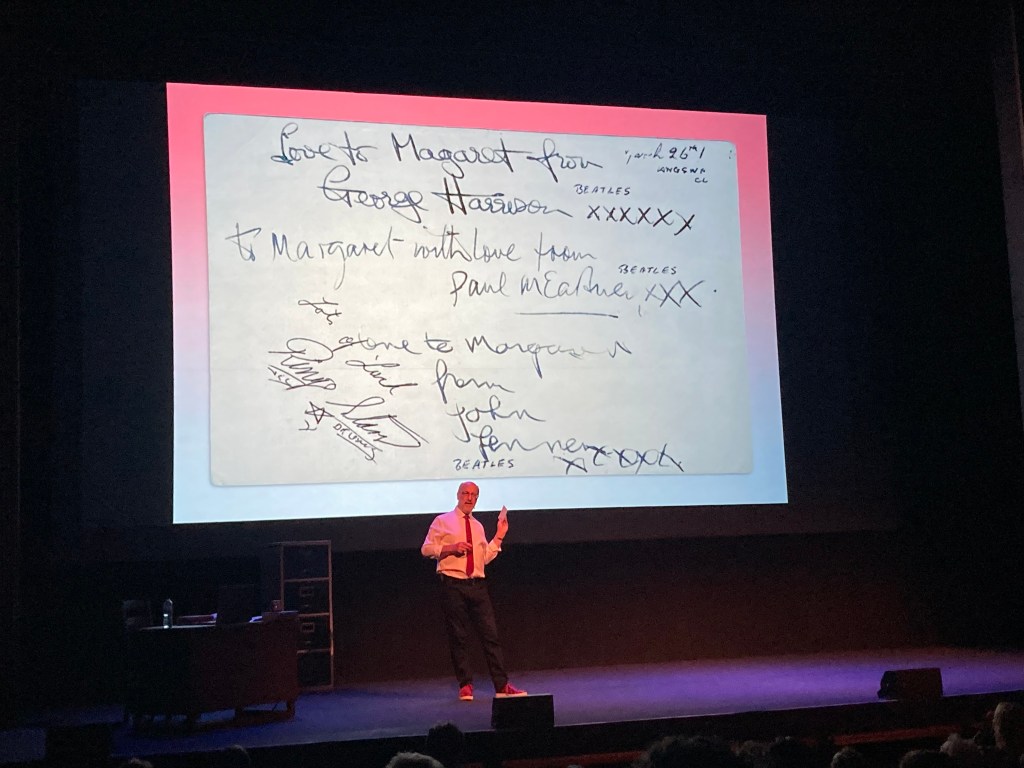

Studio Sounds is a very good album, but the earlier Frisbee is, I think, the classic. The opener came about when the Guardian asked him to write a song for National Music Day, which is what the song is called. “Fortune’s Child” is a great slice of power pop. “Do It the Hard Way” opens with the sort of quatrain you don’t find much in a pop lyric any more (except maybe from Taylor Swift): “I drive my car up a one-way street / Dirty looks from everyone I meet / I ask the Lord my soul to keep / No reply — must be asleep.” Then there’s something called “Yoko, Oh”: a homage to John Lennon in the form of a gentle, loving pastiche of the ex-Beatles at his most blissed-out. Titles like “The Action-Painting Blues”, “Baby, I Miss the Internet” and “Sunset Sound” suggest the breadth of the topics that get him writing. A song called “This New Abba Record” lives up to its title.

The eight-minute “American Baby (Two-Part Invention in C)” is the one to which I keep returning, hooked by a minor-key electric piano riff that finds the ground between the Zombies’ “She’s Not There” and the Doors’ “Riders on the Storm”, achieving a momentum almost as subtly relentless as Steely Dan’s “Do It Again”. As a song, there’s not much to it. But you could say that about many of the greatest pop records. And the potency of the groove somehow turns the blankness of its lyric into something mysterious and compelling.

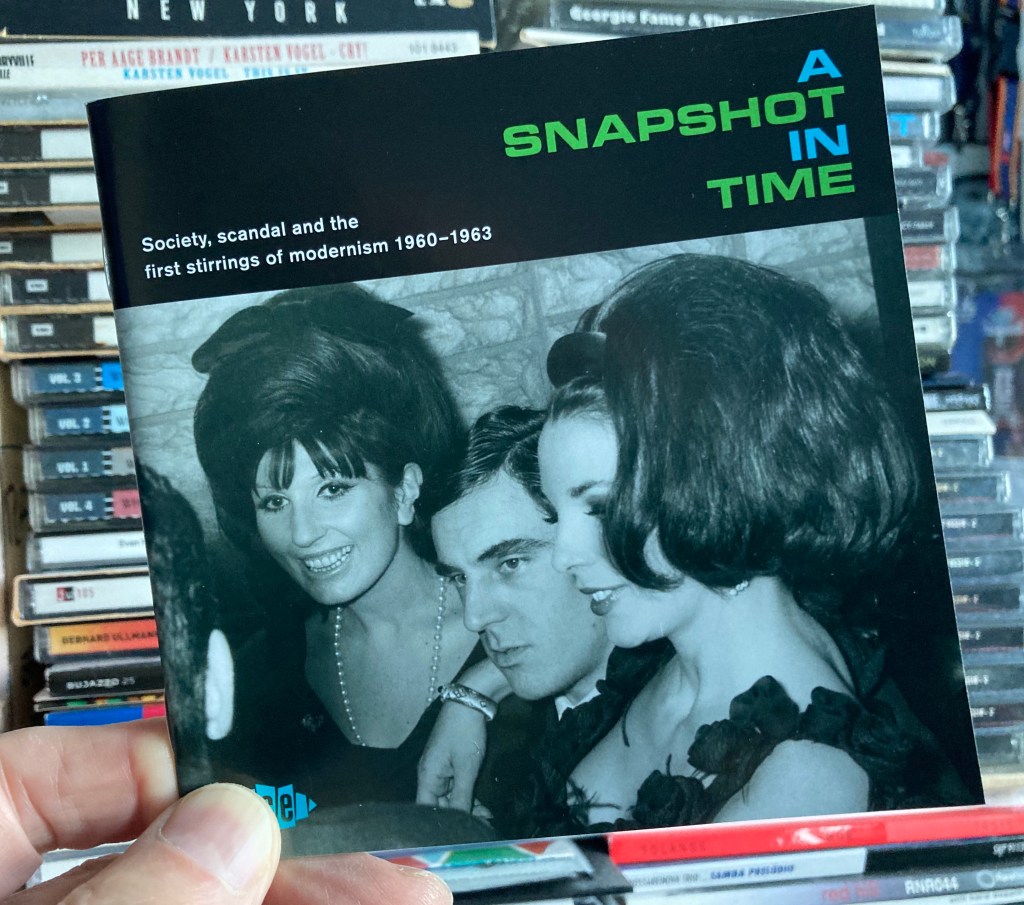

* Tot Taylor’s Frisbee and Studio Sounds are on the Campus label. The photograph of Taylor is from the sleeve of Studio Sounds. The Story of John Nightly is published by Unbound.