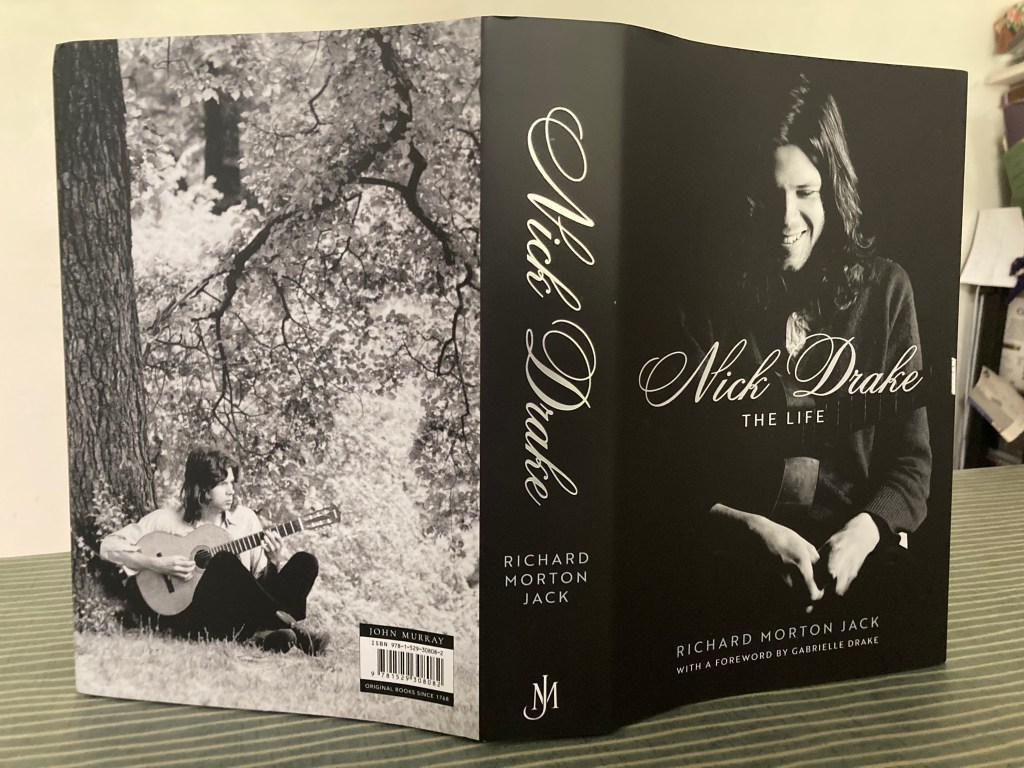

Nick Drake: The Life

You had to wonder, looking around the October Gallery in London last night, what Nick Drake would have made of the gathering arranged to mark the publication of Richard Morton Jack’s account of his short life. As his sister, the actress Gabrielle Drake, remarked in her elegantly moving speech, he might have taken it as a vindication of his own belief in his talent.

Among those present last night were many who had spoken to the author about their encounters with Drake. Among those I knew were Simon Crocker, Chris Blackwell and Jerry Gilbert. Crocker played drums at Marlborough in a band in which Drake played saxophone and later travelled with him on expeditions to Aix and Saint-Tropez; their final encounter, a few months before Drake’s death, is recounted in the book. Blackwell, the founder of Island Records, had liked Drake’s demos — and Drake himself — when he heard them at the end of Nick’s first term at Cambridge in 1967; a year later he signed him to the label at the behest of Joe Boyd, who became his producer. Gilbert, my colleague at the Melody Maker for a few months in 1970, secured the only real interview Drake ever gave, published in Sounds later that year**.

And, of course, there was Gabrielle, to whom the extraordinary way her younger brother’s posthumous reputation and record sales eventually took off must have been the source of such complex emotions: joy that he had finally been recognised, regret that he could not see and be part of it, all filtered through the memory of the mixed happiness and pain that marked his 26 years.

As she writes in the book’s foreword, this is not an authorised biography in the sense that the author’s approach or his final manuscript were formally approved by Nick’s estate or his surviving family. But Richard Morton Jack was given such generous access to all relevant sources and material, and has treated this opaque, enigmatic life with such care and skill, and with such a calm, understated ability to evoke time and place, that his 550-page volume can be considered definitive — a dangerous word when it comes to biography, or indeed any non-fiction work, but in this case almost certainly justified.

* Richard Morton Jack’s Nick Drake: The Life is published by John Murray.

** Not quite the only one, as it turns out: during his research for the book, Richard Morton Jack unearthed a 1970 interview given to a writer from, amazingly, Jackie, a magazine for teenage girls.