The man with the blue guitars

The thing about Chris Rea — who has just died, aged 74 — was that he didn’t fit anywhere, except with the people who loved his music. And sometimes they didn’t fit him, which caused a few problems. The people who bought “On the Beach” and “Driving Home for Christmas” made him rich, but their expectations could be frustrating. This was a man who also recorded pieces called “Green Shirt Blues (for George Russell)” and “Take the Mingus Train”, which seemed to show where his heart lay. Occasionally an envelope would arrive with a CD of rough mixes and things he’d been trying out in his studio; the last piece he sent me was called “Giverny and the Trenches”, an eight-minute instrumental mini-suite containing multitudes, including free-jazz saxophones.

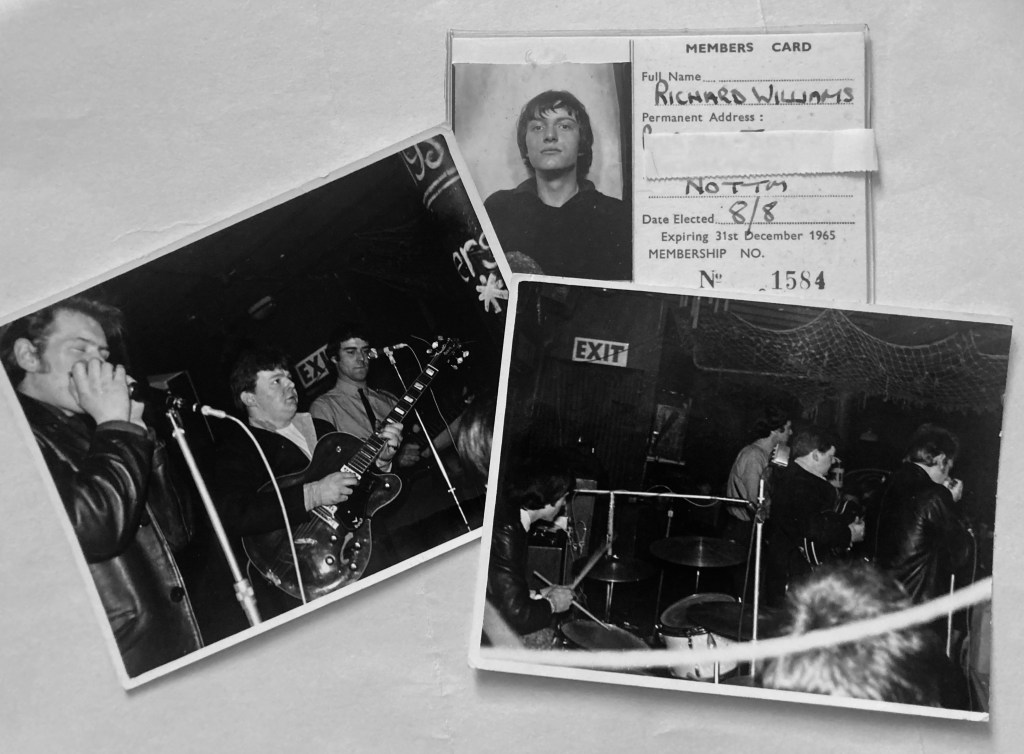

But that wasn’t the only only place his heart lay. Occasionally he’d email about something or other. The exchanges were usually brief but always interesting. One was about the R&B singer Little Johnny Taylor, whose “Part Time Love” was a favourite with the sort of mods we both were in the ’60s. He must have been to see Taylor live, possibly at Newcastle’s Club A Go Go. “How good was he!… I could smell the sweat dripping on my mohair suit (14inch single vent).”

Another time, I sent him a link to James Jamerson’s isolated bass part on “Ain’t No Mountain High Enough”, on YouTube. “Fucking wow!” he replied, and said he’d just been listening to the Temptations. “The Temps have blown me away again, even after all these years. Re-reading Berry Gordy’s book… just to be there! I must be going bonkers, got caught in the kitchen doing dance moves to ‘Get Ready’. Struggling to be bothered with what’s happening now. Only God seems to know the value of Motown.”

Chris had been a blues hound and a northern soul boy, and he never lost it, even when he seemed to be driving straight down the middle of the road. He was a proper musician, and he loved working with other proper musicians, like the keyboardist Max Middleton and the drummer Martin Ditcham, long-time associates. I doubt that this country has produced many better slide guitarists, too, but he was never flashy.

He wrote great pop songs, the sort that mean something to people, that speak to their emotions and become part of their lives: “Fool (If You Think It’s Over)”, “Josephine”, “Stainsby Girls”, “Let’s Dance”. There was always a bit more to them than just a pop song. He once told me that he’d been paid to come up with the first few lines of Hot Chocolate’s “It Started With a Kiss” — no credit, just a lot of money. Somebody else could finish it and get the publishing royalties. It’s a great song, thanks to those opening lines.

He loved to paint — cars, mountains, his collection of guitars. The Hofner violin bass above is one of his, used on the cover of an album called Hofner Blue Notes, a sequence of a dozen pieces for solo bass guitar and rhythm section. He released it in 2003 on JazzeeBlue, the label he set up in a fit of exasperation with the limits imposed by major record companies on artists who didn’t want to be forced into boxes. Artists like him.

That same year, also on JazzeeBlue, he released an album called Blue Street (Five Guitars), a beautiful series of tone poems inspired by, probably among other things, his love of Miles Davis’s Kind of Blue period. It contains a truncated version of a piece he once sent me in unfinished form, originally with the working title “Going to A Go Go”, in which he used the riff from the Miracles 1965 hit of that name to evoke the cherished memories of those happy days and in a second, slower section, to ask himself questions about what had happened to him since: “And your life is rolling over / A little faster every day / Better stop for a while and think it over / Because you know for sure you lost your way / Does what’s around you really matter / Is there something left undone /Now the truth has got you on the run…” Then he goes back to the original tempo: dancing, as he once put it, down the stony road.

The version on the album doesn’t have the sung part of the first section; maybe copyright problems got in the way. But, as much as all his greatly loved hits, Blue Street (Five Guitars) is a great testament to a man who earned the rewards of success but never quite the recognition he deserved.

The health problems he suffered over the last 25 years were hideous. The last time I saw him, he bought me dinner at a very good Italian restaurant on the Fulham Road. Italian food was another thing he knew a lot about, thanks to his dad, Camillo, who ran a chain of ice-cream parlours in and around Middlesbrough. And now I’m going to play his “Going to A Go Go”, over and over. So glad I knew him; so sad he’s gone.