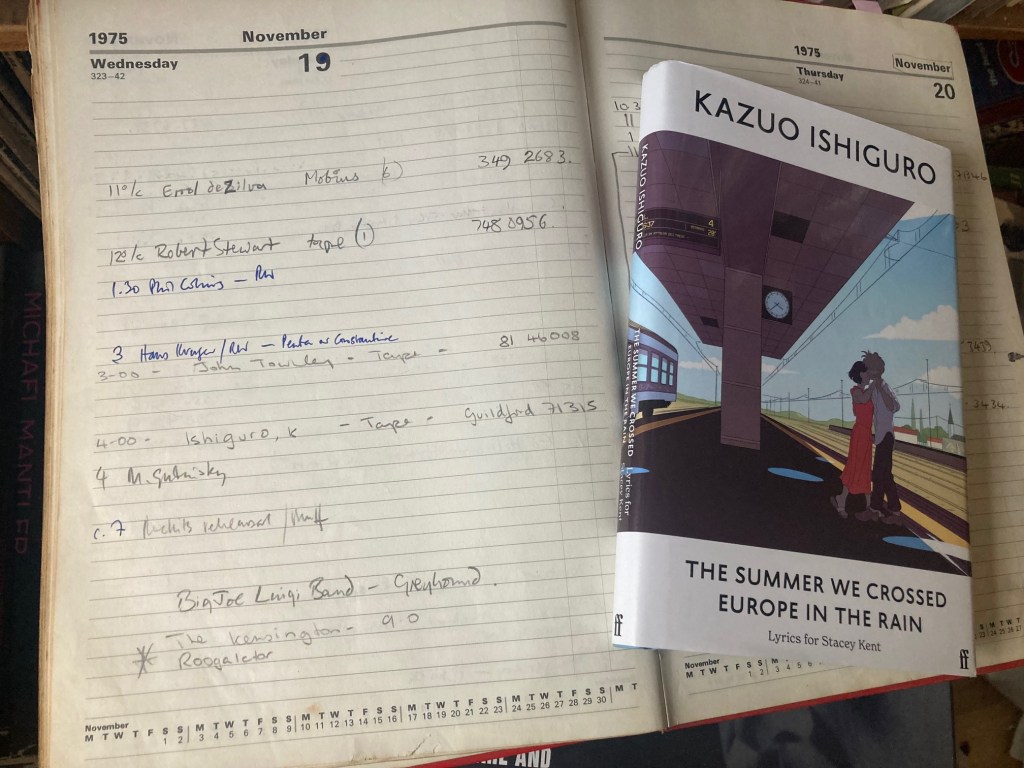

Ishiguro, long ago

A typical day in the A&R department at Island Records’ London headquarters in November 1975. Four or five people coming in to play their demo tapes to me or my assistant, Howard Thompson, in the semi-basement office in a beautiful stucco house in St Peter’s Square, W6. A lunchtime meeting with Phil Collins, a familiar face from the early days of Brand X, before they went off to sign with Charisma. The early evening rehearsal of a band called the Rockits, evidently a Muff Winwood project. And a note to go and see the still-unsigned Roogalator, with their great American guitarist Danny Adler, at the Kensington pub near the Olympia exhibition halls.

At four o’clock that day there was an appointment with “Ishiguro, K”, bringing a tape for us to hear, evidently from Guildford. Sadly, I have no clear memory of the man or his songs. What I do know is that he would go on publish the first of his eight novels, A Pale View of Hills, in 1982, win the Whitbread Prize for An Artist of the Floating World in 1986, the Booker Prize for The Remains of the Day in 1989, and the Nobel Prize in literature in 2017, all of this topped by a knighthood in 2018. So I think one could say that, just a couple of weeks past his 21st birthday and a couple of months into the first year of his undergraduate studies at the University of Kent, Kazuo Ishiguro negotiated what is nowadays known as a sliding-doors moment with some success.

I found that diary entry a couple of years ago, while looking for something else. It came back into my mind while reading the introduction to The Summer We Crossed Europe in the Rain, a book of Ishiguro’s lyrics, written over the last couple of decades for the London-based American jazz singer Stacey Kent.

“I’ve built a reputation as a writer of stories, but I started out writing songs,” he writes, before going on to describe an apprenticeship influenced by Leonard Cohen, Joni Mitchell, Bob Dylan, Robert Johnson, Jimmy Webb, Tom Jobim, Hank Williams, Hoagy Carmichael, Cole Porter and many others. He failed in his original ambition to become a successful singer-songwriter, but what’s interesting is the degree to which he believes his eventual mastery of writing fiction was shaped by his early efforts with music, which led him to think that the trick was not to prioritise getting a grip on his readers but rather to find a way of engaging their interest at a different and perhaps more lasting level.

“A song lasts only a few minutes,” he writes. “Its impact can’t afford to reside just in what happens during the moment of direct contact. A song lives or dies by its ability to infiltrate the listener’s emotions and memory, and, like a parasite, take up long-term residence, ready to come to the fore in moments of joy, grief, exhilaration, heartbrteak, whatever. No one aspires to write a song that catches the attention only while it’s being heard, then gets forgotten. That’s not how songs work.”

What he identifies is “something in the unresolved, incomplete quality of so many well-loved songs that’s significant here. In the world of prose fiction, there’s a strong impulse to achieve completeness; to tie every knot, answer every question, to leave no loose ends hanging. By contrast, in the world of songs, there’s a much lower bar when it comes to literal sense-making. The tiny amount of words available, the internal logic of the melody, the emotional content imposed by chords and chord sequences mean that the ability of a song to connect had little to do with, say, convincing psychological back stories or even the clear readability of the songs unfolding before us. It occurs to me that good songs may haunt the mind not despite their incompleteness, but because of it…”

The whole thing is worth reading, as are the 16 lyrics reproduced in the book, beautifully illustrated by the Italian artist Bianca Bagnarelli in a bande dessinée style. If the occasional specificity of places and film references recalls Clive James’s efforts in a similar direction (mentions of Casablanca and Indochine, Les Invalides, “some tango in Macao”, “Gabin / Hooded eyes / A slow Gitanes / Weary deserter on the run”), the subtlety of the emotional engagement is closer to that of Fran Landesman, the writer of “The Ballad of the Sad Young Men” and “Spring Can Really Hang You Up the Most”. Ishiguro’s lyrics are sophisticated without being smart, precise but leaving intriguing gaps; they bear reading on the page, and their effect — like that of his mature prose — can linger in the mind.

As I said, I have no real memory of what happened on that Wednesday in 1975 when “Ishiguro, K” came by. It can’t have had any effect on his destiny. But I hope we were nice to him.

* Kazuo Ishiguro’s The Summer We Crossed Europe in the Rain is published by Faber & Faber. Stacey Kent’s albums Breakfast on the Morning Tram and The Changing Lights, which contained some of the early fruits of their collaboration, set to music by Kent’s husband, the saxophonist and flautist Jim Tomlinson, were released in 2007 and 2013 respectively on the Blue Note label.