Silence and slow time

“Silence and slow time…” John Keats’s beautiful phrase finds an echo in some of the music I love, the kind that emerges from a stillness to which it eventually returns, taking its time and not raising its voice to attract attention. Here are five brand-new examples of music with healing qualities, all highly recommended.

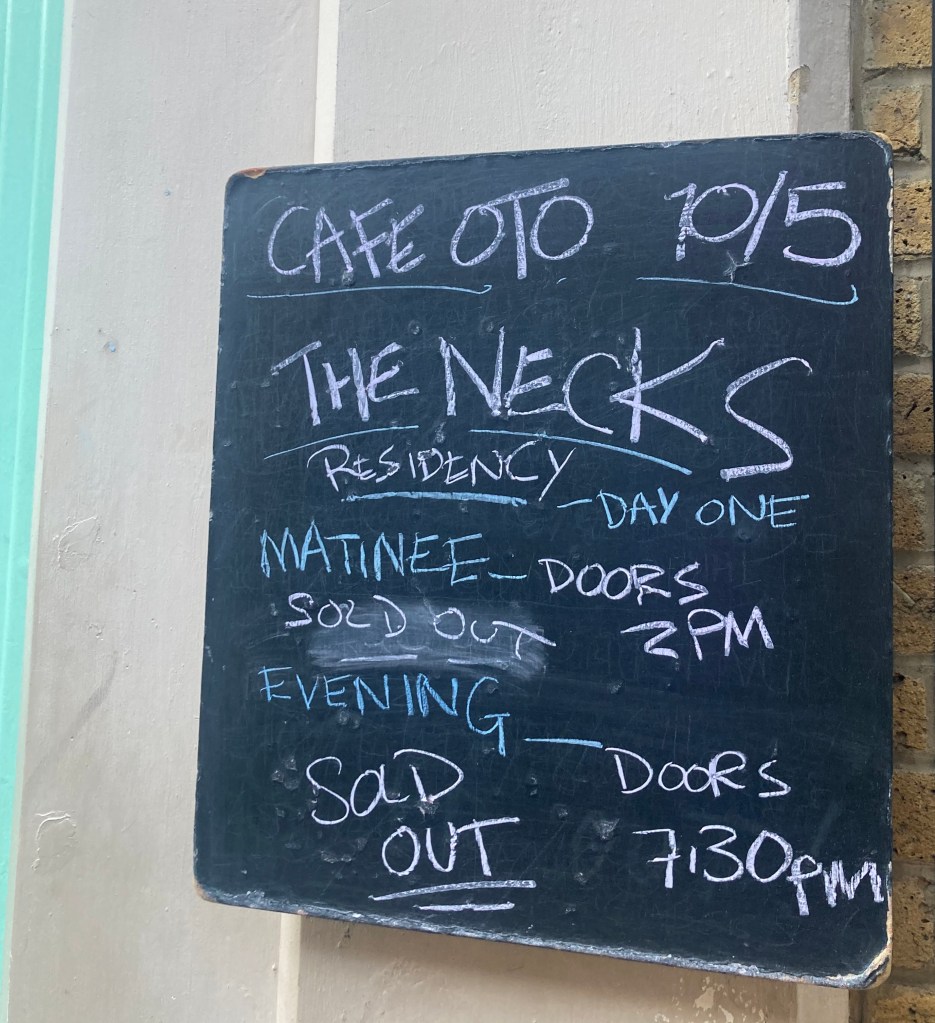

1 The Necks: Disquiet (Northern Spy)

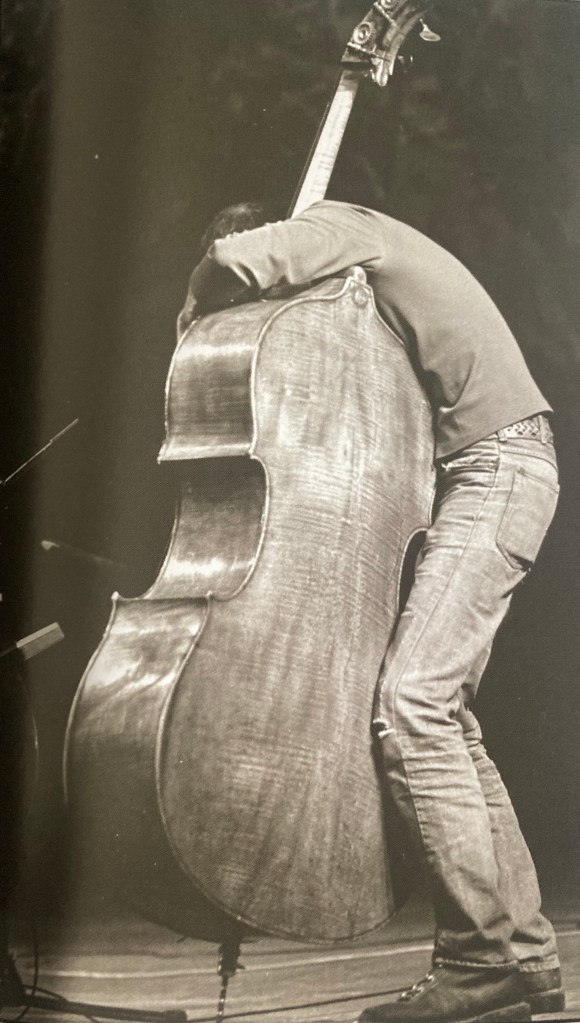

Three hours of glorious studio-recorded collective interplay on three CDs. “Rapid Eye Movement” is a 57-minute exploration of densities, starting with Chris Abrahams’ Rhodes piano, punctuated by Lloyd Swanton’s abrupt double bass figures. It changes slowly, like the weather, eventually reaching a passage of single-note cascades from the acoustic piano over Tony Buck’s rumbling tom-toms, leading to an exquisitely tapered ending. “Ghost Net” is 74 minutes of lurching, clattering, gradually darkening polyrhythmic layering, with each musician apparently playing in 12/8, but in three different 12/8s. Using what sounds like a Farfisa organ, it’s as though they’ve suddenly found the sweet spot between Thelonious Monk and ? and the Mysterians. The other two tracks divide an hour between them. “Causeway” opens with echoing guitar and celestial organ and contains a completely intoxicating E minor/B minor/A minor vamp — the Necks’ own three-chord trick — with piano above guitar and organ before a sudden gearchange, involving the addition of thrashing drums, turns a reverie into something soaringly urgent. “Warm Running Sunlight” is an essay in textures and the contemplative space between them: string bass going from plucked to bowed and back, splashing cymbals, Rhodes heavy on the reverb. A lot to take in, but among their very best, I’d say.

2 Tom Skinner: Kaleidoscopic Visions (Brownswood)

The drummer and composer whose Voices of Bishara project I liked so much, in both its studio and live incarnations, takes a slightly different tack here. The music is built around his regular bandmates — the saxophonists Chelsea Carmichael and Robert Stillman, the bassist Tom Herbert and the cellist Kareen Dayes — but with a handful of guests: Meshell Ndegeocello layering her voices on one track, Portishead’s Adrian Utley adding his guitar to a couple more, the singer Contour (Khari Lucas) from South Carolina gently intoning the poetic lyric of “Logue”, and Yaffra (London-born, Berlin-residing Jonathan Geyevu) reciting the poem “See How They Run” over his own piano and Skinner’s overdubbed keyboards, vibes, bass, guitar and percussion. Music without boundaries, full of human feelings, ancient to the future.

3 Jan Bang / Arve Henriksen: After the Wildfire (Punkt Editions)

The two Norwegians devise eight pieces featuring Henriksen’s distinctive trumpet with Bang’s samples, Eivind Aarset’s guitar, Ingar Zach’s percussion, three singers, the Fames Institute Orchestra, a cellist, two Balkan instruments — the tapan (a double-headed drum) and the kaval (an end-blown flute) — and the zurla, a Turkish double-reed instrument. Ravishing from beginning to end, starting with “Seeing (Eyes Closed)”, which made me think that Miles Davis and Gil Evans had been reincarnated as graduates of the contemporary Norwegian jazz scene, to “Abandoned Cathedral II”, a continuation of Henriksen’s classic 2013 album, Places of Worship.

4 Rolf Lislevand: Libro Primo (ECM New Series)

Another Norwegian, this time an exponent of the archlute and the chitarrone, examining the works written for the lute and its variants by the 16th and 17th century composers Johann Hieronymus Kapsberger, Giovanni Paolo Foscarini, Bernardo Gianoncelli and Diego Ortiz. Lislevand’s sleeve essay explains the revolution in which these composers were involved, and he brings them into the present day with free, fluid interpretations that make this music ageless. His own riveting “Passacaglia al Modo Mio” is both a salute and a declaration of possibilities. Anyone with a fondness for Davy Graham or Sandy Bull will enjoy this enormously.

5 Charles Lloyd: Figures in Blue (Blue Note)

For the latest in his series of drummerless chamber trios, the great saxophonist is joined by an old colleague, the pianist Jason Moran, and a newer one, the guitarist Marvin Sewell. This two-CD set begins with what is surely the first version of “Abide with Me” to appear on a jazz album Monk’s Music in 1957 and ends with a exquisite rumination on the standard “My One and Only Love”. In between Lloyd invokes the spirits of Duke Ellington, Billie Holiday, Langston Hughes and Zakir Hussain. On two tracks he also makes fine use of Sewell’s command of bottleneck techniques, leading one to wish that more modern jazz musicians would explore the blues in the way Gil Evans did with “Spoonful” and Julius Hemphill with “The Hard Blues”.