Crushed velvet

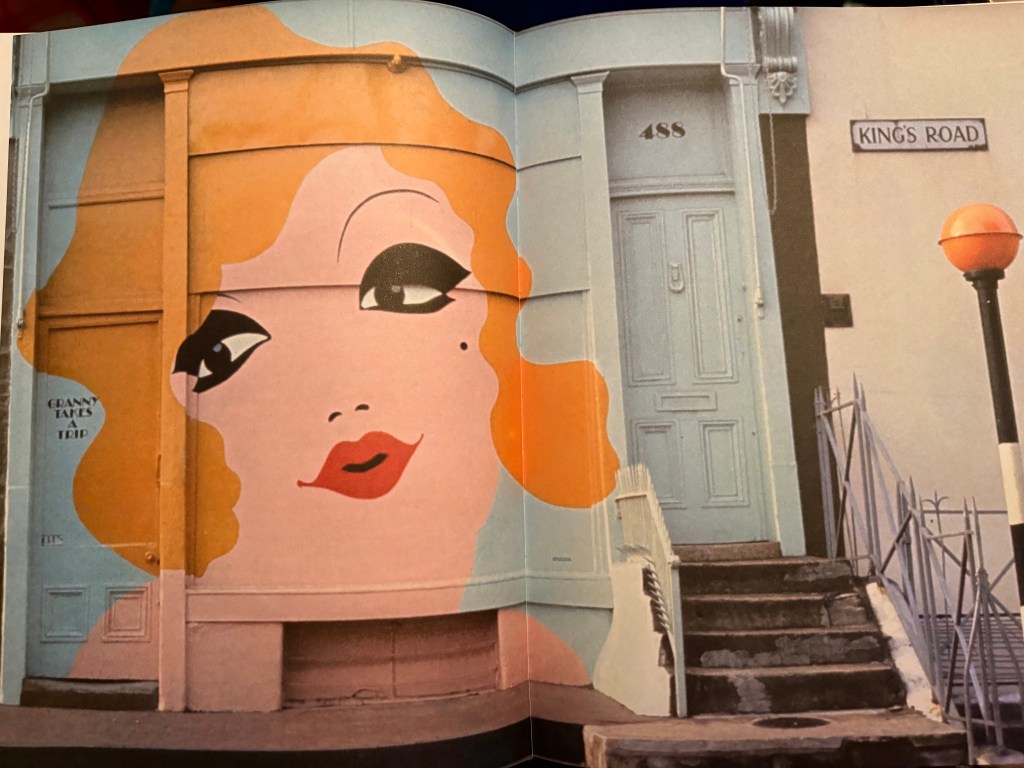

Hung on You opened at 22 Cale Street, north of the King’s Road in Chelsea Green, in 1965, followed a few months later by the arrival of Granny Takes a Trip, located 15 minutes’ walk away (or rather less by Mini-Moke) at 488 King’s Road, in the then-unfavoured bit known as World’s End. Between them, at a time of rapid change and amid a prevailing mood of exhilaration, they redefined the way fashionable young men dressed.

It wasn’t always for the better. Cast an eye over Gered Mankowitz’s photographs of the Rolling Stones from 1964/65 and you’ll find a look — reefer jackets, tab-collar shirts, maybe a leather waistcoat, straight elephant-cord trousers, Cuban-heeled boots — that seems immaculate today. Examine the same band a year or two later, and the Afghan coats, velvet flares, silk scarves and floral or satin shirts with long collars and puffed sleeves look amusing but hopelessly dated. What had happened was that they’d discovered Granny’s and Hung on You. So had the Beatles.

Dozens more rock stars flocked in their wake. Two days before he died, in September 1970, Jimi Hendrix visited Granny’s to place an order for suits, shirts, trousers and boots. By then, alas, the bloom had gone off what had once seemed so original.

Those two shops — and a handful of others, like Alkasura and Dandie Fashions, also on the King’s Road — had caught a pivotal moment in the metamorphosis from mod to hippie, from restraint to excess. Trends are often at their most interesting when they’re in transition, when (as Gramsci put it) the old is dying and the new is struggling to be born. As with everything, success attracts exploitation. And then it goes too far.

How it started, and how it ended, is chronicled with great thoroughness in Paul Gorman’s Granny Takes a Trip, subtitled “High Fashion and High Times at the Wildest Rock ‘n’ Roll Boutique”. Gorman tells the story well, with plenty of first-hand testimony from the survivors and a lot of illustrations — clothes, shopfronts, magazine and newspaper cuttings — but by the time I’d finished it, I felt it was one of the saddest books I’ve ever read.

Sixty years ago I lusted after some of the earliest clothes produced by Nigel Waymouth, Sheila Cohen and John Pearse at Granny’s and particularly by Michael Rainey and Jane Ormsby-Gore at Hung on You, often modelled in Men in Vogue or Town magazine by young exquisites such as the antiques dealer Christopher Gibbs and the interior designer David Mlinaric. Sadly, 100-odd miles and a suitable income away from the King’s Road, that lust was destined to remain unrequited.

While Hung on You faded out at the end of the ’60s, Granny’s — where the front end of Pearse’s 1948 Buick pick-up had been sawn off and painted yellow to form a late version of the ever-changing shopfront — was taken over by a man named Freddie Hornick, whose big plans eventually included branches in New York and Los Angeles. Rock stars continued to shop there, but Rod Stewart in a leopard-print suit, Elton John in zebra stripes and Todd Rundgren in a suit embroidered with harebells were no longer even cool, never mind at fashion’s leading edge.

For too many of the participants, the bright beginnings were eaten away by drugs. The body-count in the second half of Gorman’s narrative is horrendous, making it hard to recreate the sense of euphoria and optimism once generated by the sight of a perfect double-breasted velvet jacket like the one from Hung on You worn by George Harrison on the back cover of Revolver in 1966.

Among the survivors is John Pearse, still making beautiful clothes at his premises on Meard Street in Soho. About 10 years ago I gathered together all my pocket money and bought a plain dark blue double breasted jacket from him. It seemed like a homage, however belated, to a year or two when the air seemed filled with the intoxicating scent of something new and good.

* Paul Gorman’s Granny Takes a Trip is published by White Rabbit (£40). The photograph of the façade of Granny’s in 1967 is from the book and was taken by David Graves.