Around John Prine

One night in January 1985 Bonnie Raitt was joined on the stage at the Arie Crown Theatre in Chicago by John Prine. They sang Prine’s “Angel from Montgomery”, which had first been heard on his debut album in 1971 and which Raitt had covered on her 1975 album Streetlights.

Raitt takes the first verse — “I am an old woman, named after my mother / My old man is another child that’s grown old / If dreams were thunder and lightnin’ was desire / This old house would’ve burnt down a long time ago.” Prine joins in as they sing the chorus in unison, an octave apart: “Send me an angel that flies from Montgomery / Make me a poster of an old rodeo / Just give me one thing that I can hold on to / To believe in this livin’ is just a hard way to go.”

So far, so lovely, so resonant. But then the magic happens. Raitt steps back and merges into her band as Prine starts the second verse alone, his parched, papery, barely-there voice only just holding on to the melody: “When I was a young girl, I had me a cowboy / He weren’t much to look at, just a free-ramblin’ man / But that was a long time, and no matter how I tried / Those years just flow by like a broken-down dam.”

It’s a song full of mystery and allusion cloaked in the mundane, and the gender-switch somehow gives it an extra layer of — what? — rubbed-raw pathos? humdrum tragedy? Don’t ask me to explain. It’s there. The audience in the Arie Crown Theatre recognises it as soon as Prine starts singing, and so will you. For me, his singing of those first words creates one of the most electrifying musical moments I know.

Raitt finishes it off with the third verse: “Well there’s flies in the kitchen, I can hear ’em, they’re buzzin’ / And I ain’t done nothin’ since I woke up today / How the hell can a person go to work in the morning / Come home in the evening and have nothing to say.” What a masterpiece of the songwriter’s craft.

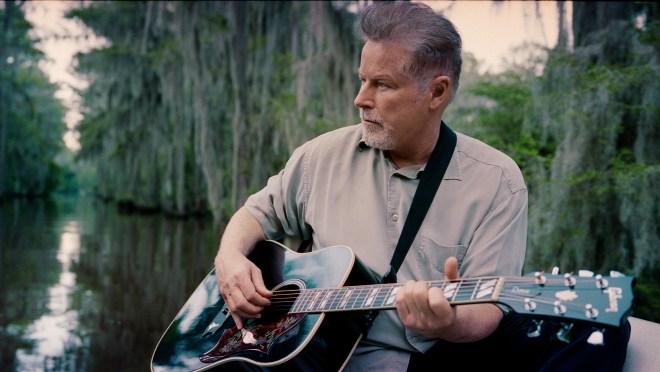

Anyway, I’ve just been listening to Prine’s last album. Called The Tree of Forgiveness, it was released in 2018, two years before his death in the first month of the Covid-19 pandemic. Although it joins Leonard Cohen’s You Want It Darker and David Bowie’s blackstar as a work conceived in the shadow of an impending exit, its mood is cheerful and thoughtful and intimate and infinitely congenial and sometimes mordantly humorous. Every one of the 10 tracks, produced by Dave Cobb at RCA in Nashville, has something to commend it.

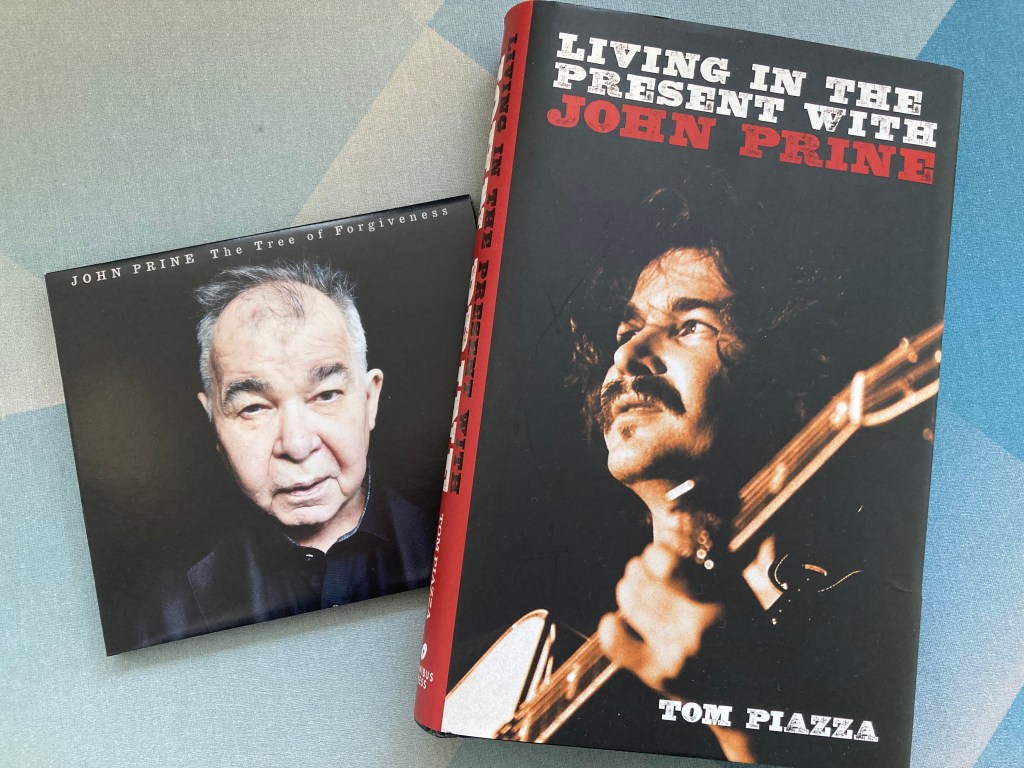

I’ve also been reading Tom Piazza’s just-published Living in the Present with John Prine. A musician and author of many well received books on such subjects as Alan Lomax, New Orleans and the bluegrass musician Jimmy Martin, Piazza met Prine only two years before his death, while writing a piece on the singer-songwriter for the Oxford American magazine.

They got on so well that Prine invited Piazza to help him write his autobiography. They spent time in each other’s company at Prine’s homes in Nashville, Tennessee and Gulfport, Florida, going to restaurants, driving around in Prine’s prized 1977 Cadillac Coupe de Ville, playing songs to each other and together. They had time for only two sessions with a recording machine before Prine died; not enough for the kind of book they had planned but enough for Piazza to write this warm, affectionate sketch of the singer-songwriter in his last years, reminiscing and enjoying the love and respect of those close to him.

Late in the book there are some vivid memories of encounters with Cowboy Jack Clement, Johnny Cash, Chet Atkins and, most surprisingly, Phil Spector, with whom Prine wrote a song called “God Only Knows”, which appears on the final album. There’s quite a lot of talk about guitars, too. Piazza writes with a sensitivity to mood, an observant eye and an easy grace that make this not just a singularly enjoyable book but the best possible way of remembering its subject.

* Tom Piazza’s Living in the Present with John Prine is published by Omnibus Press. Prine’s The Tree of Forgiveness is on Oh Boy Records. The version of “Angel from Montgomery” described here was included in The Bonnie Raitt Collection, released in 1990 on Warner Brothers.

It had been an enjoyable enough concert for the first 40 minutes or so, but when Lucinda Williams dismissed her band and introduced “The Ghosts of Highway 20”, the mood of the evening deepened. “I’ve been filled with the need when I’ve sung this song lately to say that not everybody from the South is a bad person,” the woman brought up in Louisiana, Mississippi and Arkansas told the crowd at the Shepherd’s Bush Empire. They knew what she was getting at.

It had been an enjoyable enough concert for the first 40 minutes or so, but when Lucinda Williams dismissed her band and introduced “The Ghosts of Highway 20”, the mood of the evening deepened. “I’ve been filled with the need when I’ve sung this song lately to say that not everybody from the South is a bad person,” the woman brought up in Louisiana, Mississippi and Arkansas told the crowd at the Shepherd’s Bush Empire. They knew what she was getting at.