In memoriam

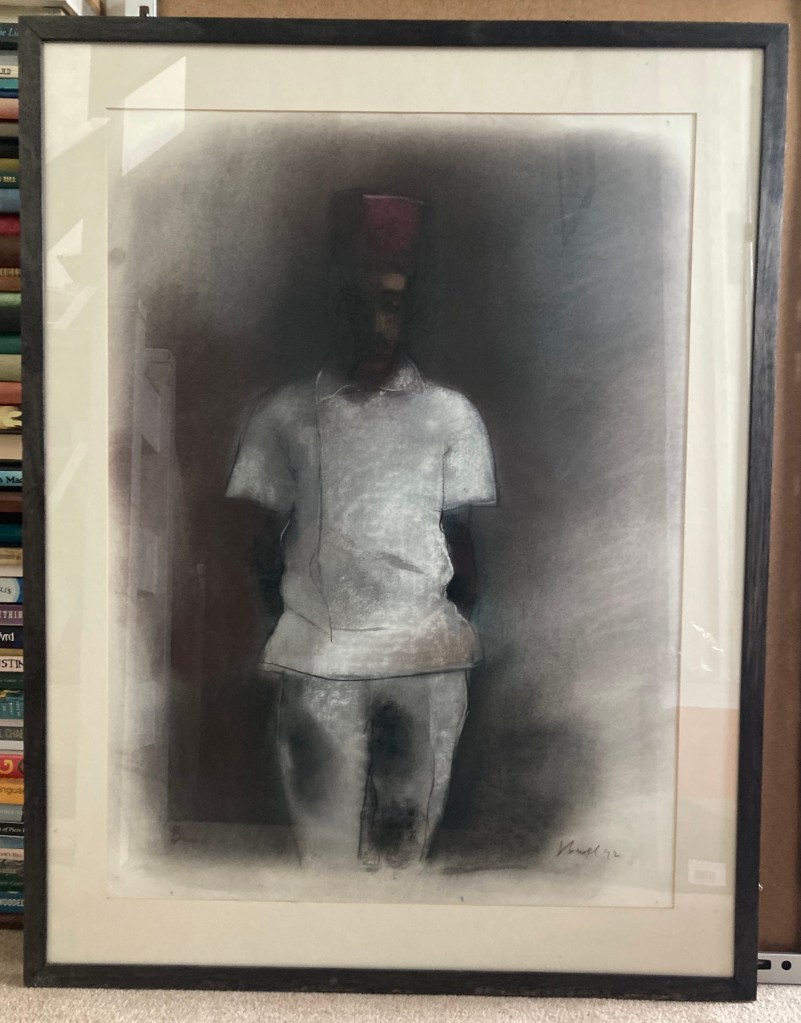

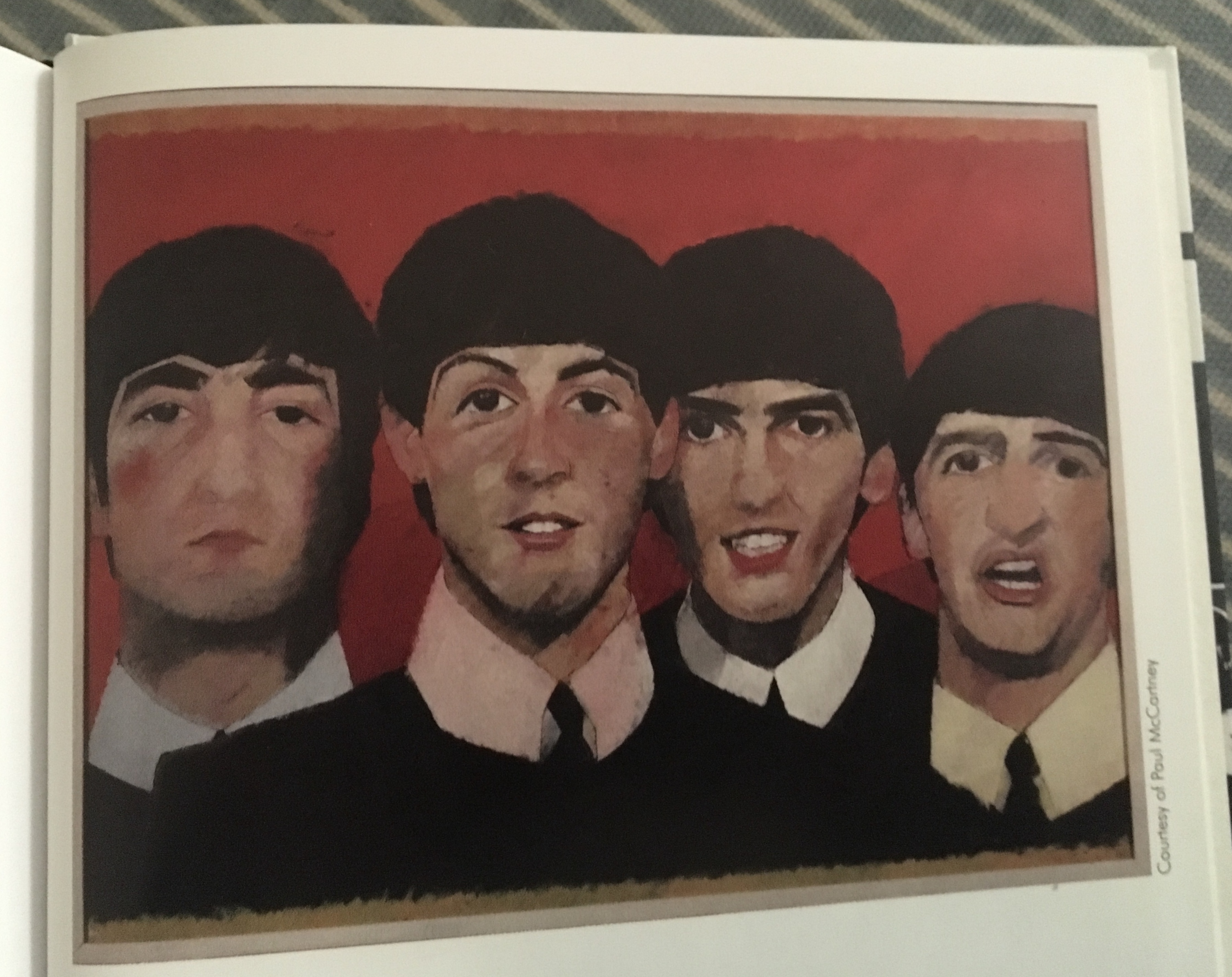

The Royal Academy’s current show of paintings by Kerry James Marshall, born in Birmingham, Alabama in 1955, is so full of colour and decoration (hard reds, electric blues, sizzling pinks, gold and silver braid), all contrasting with the fathomless black of his skin tones, that it might seem perverse to choose the most subdued piece on view. But when you examine “Souvenirs IV”, it’s not not surprising that it should have made an impact on me.

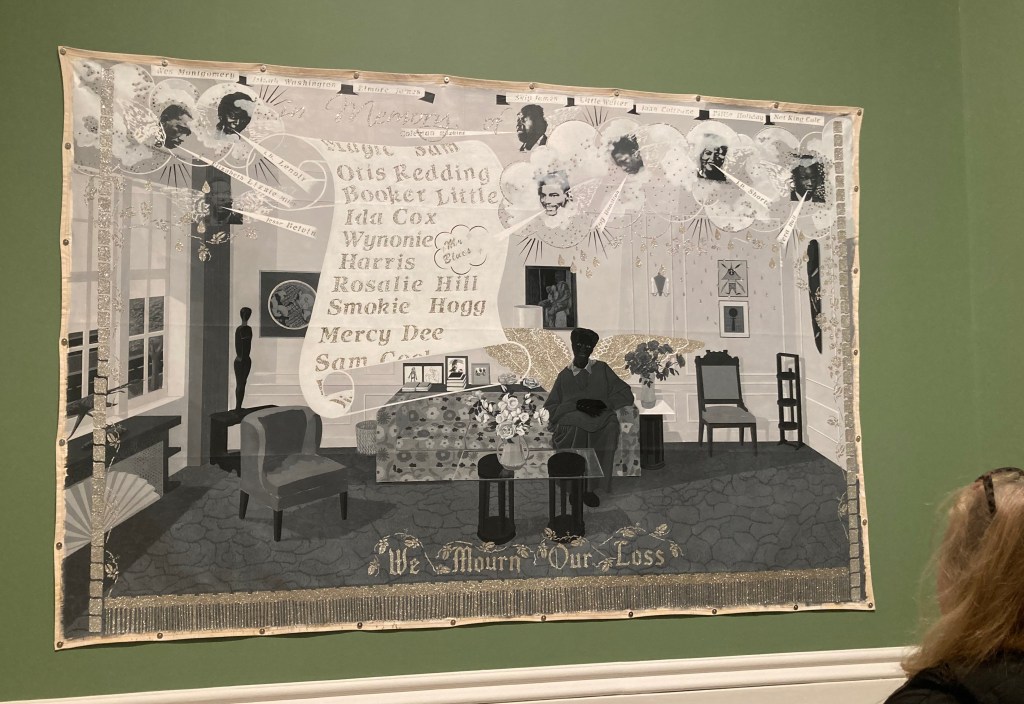

Each of the four large (13ft wide by 10ft high) works in this 1998 series occupies a wall of the octagonal room at the centre of the gallery. Executed in acrylic, glitter and screenprint on paper on tarpaulin, attached to the walls by visible grommets, they are memorials to dead heroes, their domestic settings subtly adorned with African symbols. Three of them feature Martin Luther King, Jack and Bobby Kennedy, and a variety of political and literary figures from black history. But “Souvenirs IV”, painted in grisaille, is dedicated to music, and includes some interesting figures.

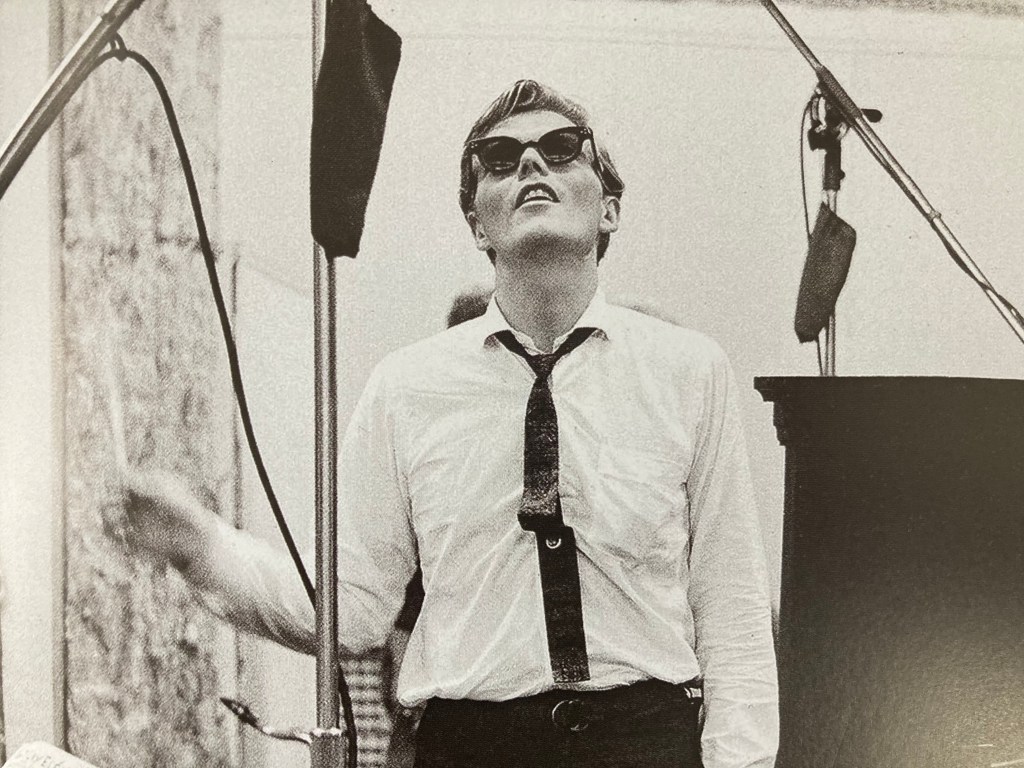

Across the top we see the names of Wes Montgomery, Dinah Washington, Elmore James, Skip James, Little Walter, John Coltrane, Billie Holiday and Nat King Cole. Beneath the frieze of those names are their pictures, each with a kind of speech trumpet giving the name of another musician: Jesse Belvin, Lizzie Miles, J. B. Lenoir, Coleman Hawkins, Roy Hamilton, J. D. Short, Vera Hall. And streaming down the centre of the painting is a banner containing more names: Magic Sam, Otis Redding, Booker Little, Ida Cox, Wynonie Harris, Rosalie Hill, Smokie (sic) Hogg, Mercy Dee (Walton), Sam Cooke.

What a very intriguing selection, running from country blues and Chicago blues through gospel, R&B and soul to jazz from New Orleans to the avant-garde. As well as the obvious greats, some of my long-time lesser-known favourites are there: Lenoir, Belvin, Little. There are others I’ll have to look into. One is Lizzie Miles (1895-1963), born Elizabeth Landreaux in New Orleans, who sang with Freddie Keppard and visited Europe in the 1920s, performed throughout the US with Paul Barbarin, Fats Waller and George Lewis, and retired from secular music in 1959 to live among an order of black nuns in her home city. Another is Rosalie (Rosa Lee) Harris (1910-68), a Mississippi hill country blues singer and guitarist recorded by Alan Lomax in 1959. A third is J. D. Short (1902-62), a cousin of his fellow Mississippi blues singer-guitarists Big Joe Williams and Honeyboy Edwards.

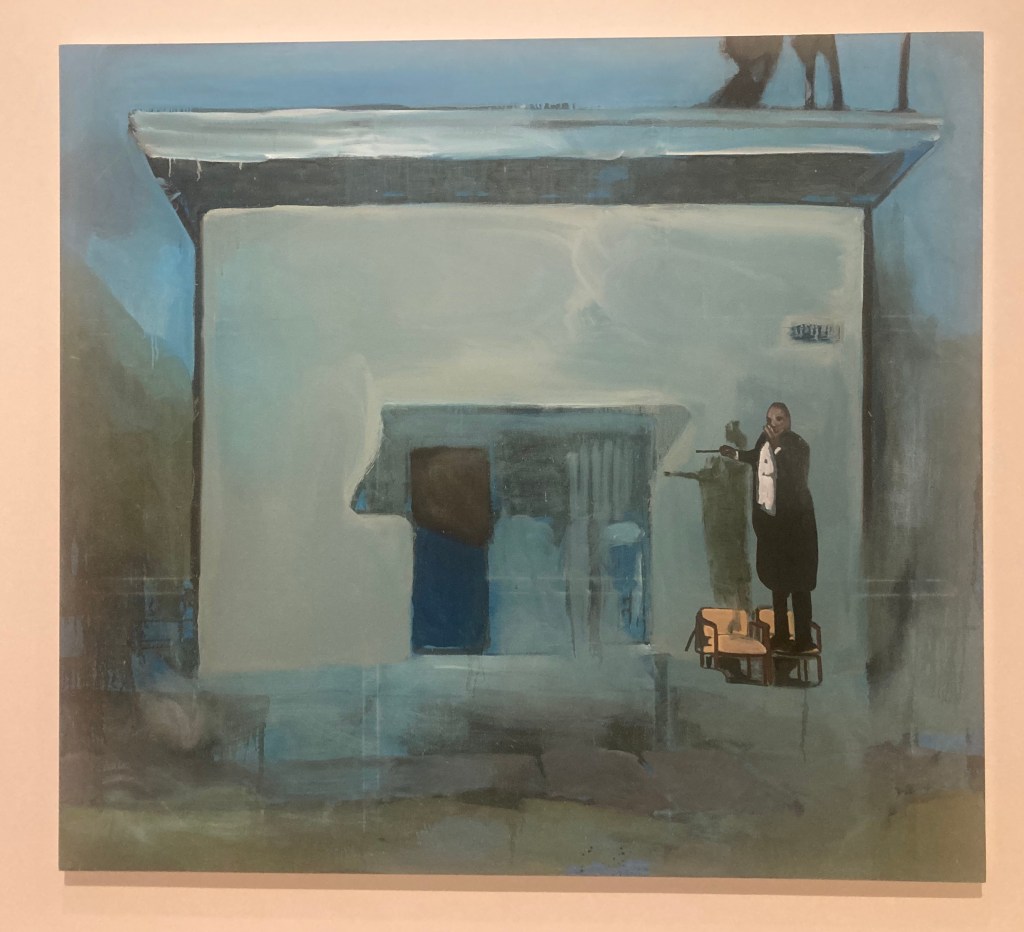

There are other fine things in the exhibition, which is titled The Histories. I spent quite a lot of time looking at a spectacular painting called “Untitled (Club Scene)” and at the enigmatic “Black Painting”, which reveals its story only when the eyes have become accustomed to its tonal grading. But “Souvenir IV” is the one that spoke to the importance of black culture in my own life, and the great debt thus incurred.

* Kerry James Marshall’s The Histories is at the Royal Academy, London W1, until January 18, 2026.