The music of Gatsby

The moon had risen higher, and floating in the Sound was a triangle of silver scales, trembling a little to the stiff, tinny drip of the banjoes on the lawn.

Coinciding with the first publication of The Great Gatsby a hundred years ago (April 10, 1925), a new musical version of F. Scott Fizgerald’s masterpiece opens shortly in the West End of London. The trailer for this latest iteration of Gatsby makes it look like an all-singing, all-dancing, good-time entertainment. It would be unfair to prejudge, but the songs by Jason Howland and Nathan Tysen certainly sound as though they adhere to the Rice/Lloyd-Webber template for modern musical theatre.

Not much room there, one imagines, for the darker undertones beneath the careless rapture, for the portrayal of the corruption of extreme wealth (and the swipe at racism) that gave Fitzgerald’s narrative a resonance which has kept it alive in the minds of its readers for a hundred years.

The musical aspect of the original novel is hardly its most significant feature, but it does provide the story with an intermittently intriguing soundtrack. Early on, for instance, there’s a band at Jay Gatsby’s house playing something he describes as “yellow cocktail music” — and even though you may not be able to define it, you know exactly how it might sound. And that “stiff, tinny drip”: I can’t hear a banjo in a band playing early jazz without those words — as good as Whitney Balliett or Philip Larkin — coming to mind.

At another of Gatsby’s summer parties on his estate, where “in his blue gardens men and girls came and went like moths among the whisperings and the champagne and the stars,” is something titled “Vladmir Tostoff’s Jazz History of the World”. A composition on a grand scale, we’re told that it was first performed at Carnegie Hall, where it created a sensation. Now it’s delivered on the lawn to Gatsby’s guests by an orchestra that was “no five-piece affair, but a whole pitful of oboes and trombones and saxophones and viols and cornets and piccolos, and low and high drums.”

Nick Carraway, Fitzgerald’s narrator, doesn’t tell us what Mr Tostoff’s work actually sounds like, at least not in the final published version. In a passage Fitzgerald deleted from a draft manuscript, Nick describes it as “starting with a weird spinning sound, mostly from the cornets. Then there would be a series of interruptive notes which coloured everything that came after them, until before you knew it they became the theme and new discords were opposed outside. But just as you’d get used to the new discord one of the old themes would drop back in, this time as a discord, until you’d get a weird sense that it was a preposterous cycle, after all. Long after the piece was over it went on and on in my head — whenever I think of that summer I can hear it yet.”

The year before the book appeared, George Gershwin’s “Rhapsody in Blue” had received its première at the Aeolian Hall in New York, performed by the 23-piece Paul Whiteman Orchestra, with the composer at the piano. Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald were living in Great Neck, Long Island at the time. Whiteman had commissioned the piece, orchestrated by Ferde Grofé, for a concert called “An Experiment in Modern Music”. It’s what I imagine Tostoff’s music must have resembled.

A few chapters later there’s also young Ewing Klipspringer, Gatsby’s house guest, roused from his sleep one afternoon and reluctantly acceding to his host’s request to play the piano, despite claiming to be out of practice. He responds with “The Love Nest”, a song by Louis A. Hirsch and Otto Harbach from a 1920 George M. Cohan musical titled Mary, while thunder rumbles and summer rain falls outside on Long Island Sound.

Three years after The Great Gatsby‘s publication, Paul Whiteman would assemble his orchestra in New York to record an arrangement of “The Love Nest”. It’s nothing special until, just before the end, Bix Beiderbecke steps forward for a sublime eight-bar cornet solo that perfectly evokes what we imagine to be the spirit of the Jazz Age.

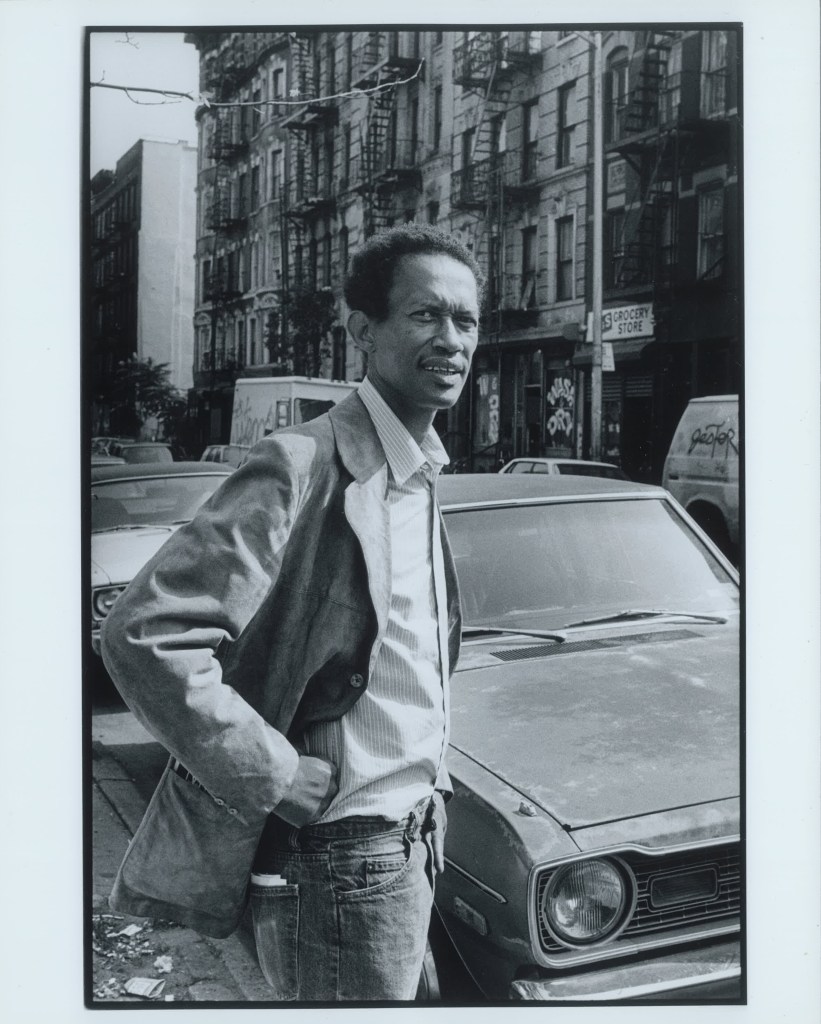

Finally, when Daisy Fay is enjoying the social life of Louisville, Kentucky while Gatsby, her besotted swain, is making his way back from army service in the Great War, she is “young and her artificial world was redolent of orchids and pleasant, cheerful snobbery and orchestras which set the rhythm of the year, summing up the sadness and suggestiveness of life in new tunes. All night the saxophones wailed the hopeless comment of the ‘Beale Street Blues’ while a hundred pairs of golden and silver slippers shuffled the shining dusk.” Written by W. C. Handy in 1917, the song was a hit in 1921 for Marion Harris, who recorded many blues songs and was perhaps the first white female vocalist to achieve success by imitating (rather than caricaturing) the style of black singers.

In a wonderful piece for the FT at the weekend, seeking Gatsby‘s echoes in our present condition, the author Sarah Churchwell concluded that the book “anticipates precisely the kind of society that would find Trumpism appealing: a culture losing its imaginative capacity, surrendering its ideals… The Great Gatsby captures a truth that repeats across generations: the powerful consolidate their control even as the dream of something better gleams ahead. Again and again, those with wealth and privilege fortify themselves against the possibility of a more just or democratic world, transforming progress into another cycle of entrenched power.”

Oh, well. Roll over, Vladmir Tostoff, and tell George Gershwin the news.

* The passage of musical description deleted from a draft of Gatsby is quoted from Some Sort of Epic Grandeur, Matthew J. Bruccoli’s biography of Fitzgerald, published in the UK by Hodder & Stoughton in 1981.