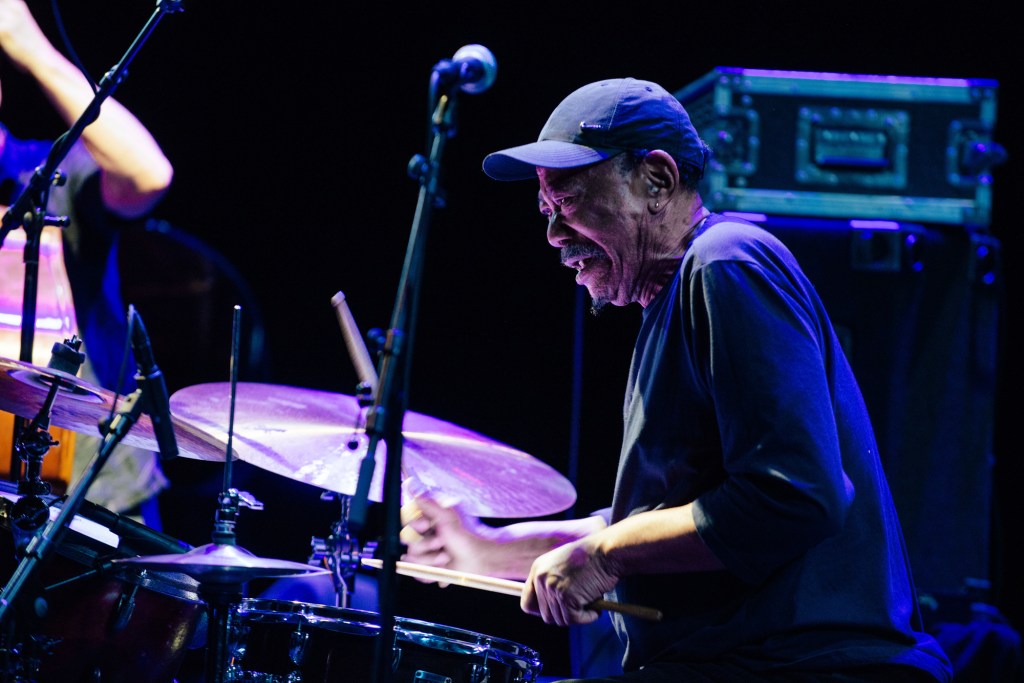

Brian Wilson meets his fans (1988)

On September 24, 1988, at the parish hall of Our Lady of the Visitation in Greenford, a West London suburb, Brian Wilson paid an unannounced visit to the annual convention of Beach Boys Stomp, a UK fanzine founded a decade earlier. This is a photograph I took that afternoon, unearthed while I was looking through some boxes of old stuff recently.

Brian was in London to promote his first solo album, with his notorious shrink, Eugene Landy, by his side. Somehow the convention’s organisers, Mike Grant and Roy Gudge, persuaded him to attend their event, overriding Landy’s objections, while managing to keep it a secret from the 325 attendees until the curtains parted on the small stage to reveal him seated at a Yamaha DX7 keyboard.

The pandemonium and applause lasted several minutes. Brian absorbed it all with equanimity before giving us solo performances of three songs. Two of them, “Love and Mercy” and “Night Time”, were from the new album. The first, though, was “Surfer Girl”. Yes, really. “Surfer Girl”. The song he’d written and recorded in 1963. Later he claimed it was actually his first attempt at songwriting. The Beach Boys’ first hit ballad, it reached the top 10 in the US and became the title track of their third album. Its doowop-influenced coda gave a clue to the riches of harmony singing to come, with a repeated question — “Do you love me, do you, surfer girl?” — that could much later be read as a hint of insecurities beneath the sunkissed surface.

His voice was a little unsteady to start with, but the falsetto was still in working order. “Thought we’d give you a little surprise today,” he said after that opening song. The other two were performed with increasing confidence and, in the case of “Night Time”, the encouragement of a steady 4/4 handclap from the audience.

The photo tells the rest of the story. Physically in decent shape, far removed from the heavily bearded 300lb creature he had been, Brian shook many hands before making his departure. In a troubled life, in that humble setting, it seemed like an unexpected but real moment of grace.