Portrait of the artists

Bryan Ferry might have made a career for himself as a painter or ceramicist, and he had a go at both. Instead he chose music. But everything he’s done since has been about being an artist in a very particular sense. Roxy Music worked best when seen as an art project: “Re-make / Re-model”, “In Every Dream Home a Heartache”. The same could be said of his solo work: the readymades of These Foolish Things, the more-than-homage of Dylanesque, the ’30s glide and swoon of As Time Goes By, the brazen charm of The Jazz Age, the wintry covers of “Back to Black” and “Johnny and Mary”.

I’ve been thinking about that while listening to his latest release, Loose Talk, created in partnership with the poet and painter Amelia Barratt, which is immediately interesting because it’s a collaboration between artists at very different stages of their careers (she is in her thirties, he will be 80 in September). It’s also the first Ferry album on which someone else is responsible for the words and their delivery.

He’s a great assembler of words himself, of course, as his collected Lyrics underlined when it was published by Chatto & Windus three years ago, but it’s often been a painful business for him. I remember stories from the ’70s of his then-manager, the department store heir Mark Fenwick, sitting in an armchair sighing and tapping his fingers like an exam invigilator while Bryan struggled to carve out the words of the final verse to the last song for a new album, its release date already postponed by a record company impatient for product.

Loose Talk is an album in which Barratt reads eleven of her poems to Ferry’s musical settings, some using material set aside from his earlier projects. It would be flippant — and wrong — to suggest that he’s solved a problem by delegating the job of providing the words to a collaborator. It’s a legitimate artistic project, from both perspectives.

Barratt is a slender young woman with the sort of looks Cecil Beaton captured in his photographs of the pre-war Bright Young Things. Her voice is quiet, reserved, unemphatic. It’s a voice you might overhear amid the gush and babble at a party — a gallery opening or a book launch, perhaps — and look around to discover its source.

Her verses are not song lyrics: they’re poems, allusive and enigmatic and unresolved, filled with fleeting exchanges that hint at narrative but yield impressions rather than stories, occasionally threaded with contemporary images: “Wasting her time / she’s flipping channels with the remote control” or “My sneakers now washed / hang by their laces.” When combined with Ferry’s music, they take us to familiar territory: “She’s one to watch” is the first line of a track called “Stand Near Me”, a prime Ferry opening if I ever heard one, while “Pictures on a Wall” provides a neon-splashed groove that might have come from any Ferry session from Horoscope/Mamouna in the early ’90s to Avonmore in 2014.

There are decayed pianos being played in abandoned ballrooms, a mood that Ferry has explored with and without Roxy Music. Often the accompanying cadences descend with slow, muted elegance: the echoing piano on “Florist”, the bass on “Orchestra”. That’s another Ferry signature.

Barratt’s poems work for me, mostly, because her delivery sounds like a modern way of speaking and sometimes she produces a sketch whose images and emotions provide a satisfying coherence. “Florist” has an intriguing arc and a moment of piercing disquiet: “Imagine one day / he comes to me and says / There is nothing more I want than this / He gestures to the tulips / that look out from a bucket, bunched / in the passenger seat of the van / To his apron / To his diary with nothing in / and I say / That’s perfectly fine / Perfectly alright / Perfectly without the need to tell me all the time.”

There are some familiar names in the credits — the guitarists Neil Hubbard and Ollie Thompson, the bassists Neil Jason and Alan Spenner, the drummers Paul Thompson and Andy Newmark — but their individual presences are never noticeable: these tracks are stripped back to form a watchful background. The most assertive music comes in the final piece, the title track, where Barratt’s economical verses are accompanied by a subdued but baleful 12-bar blues, somewhat in the manner of “Let’s Stick Together”, Ferry’s 1976 solo hit.

Ferry’s own voice is allowed to peep through two or three times as a kind of palimpsest, probably leftover guide vocals from the demos, notably on “Orchestra”, where the atmospherics are at their most languid and dream-like. But in this collaboration he’s found another way to extend his expressive reach. It’s the latest episode in a long life full of interesting creative decisions. Another twist in an artist’s career.

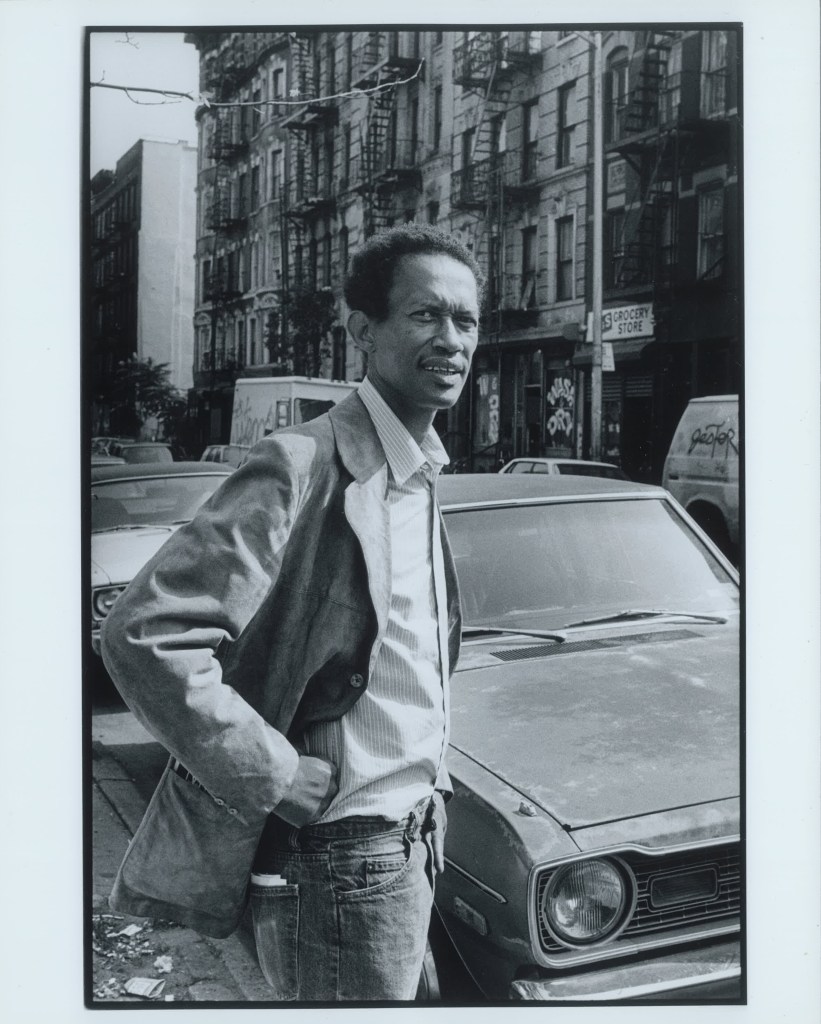

* Loose Talk by Amelia Barratt and Bryan Ferry is out on Dene Jesmond Records on March 28. The photograph of Ferry and Barrett was taken in Los Angeles by Albert Sanchez.