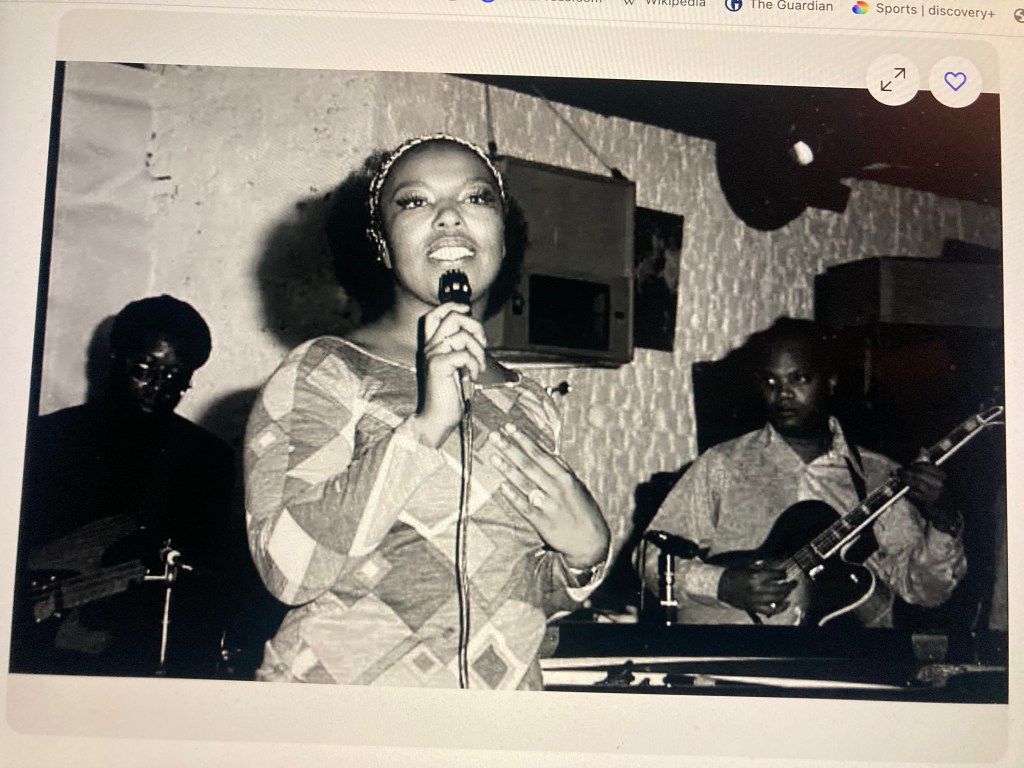

Roberta Flack in London

Roberta Flack, who has died aged 88, made her London debut on July 27, 1972, at an early-evening showcase presented by Atlantic Records before an invited audience of industry and media types at Ronnie Scott’s Club. She’d already released three albums but it was when Clint Eastwood chose to feature a track from the first of them, “The First Time Ever I Saw Your Face”, in his 1971 movie Play Misty For Me that she became a hot property.

I sat with my friend Charlie Gillett and we were both overjoyed to discover that her band included Richard Tee on keyboards, the guitarist Eric Gale and the drummer Bernard “Pretty” Purdie. A real New York studio ‘A’ team, the kind you couldn’t quite believe you were seeing in a London club. They provided the perfect platform for the poise and exquisitely chosen material of a singer who was already, at 35, a mature woman.

Of a beautiful little show, in which she also presented two talented young male singers who were her protégés (and whose names I’m afraid I don’t recall), the highlight for me was “Reverend Lee”, a slice of lubricious lowdown funk written by Eugene McDaniels, to whom she had been introduced by her original patron and mentor, Les McCann. She’d already recorded McDaniels’ “Compared to What” on her debut album, First Take, released the day before before McCann and Eddie Harris cut their hit live version at the Montreux Festival.

I prefer her reading, in which the incendiary lyric of a great protest song is rendered all the more powerful for her restrained delivery. Produced with exemplary sensitivity by Joel Dorn, it features the great Ron Carter on double bass, shortly after he had ended his six-year stint with Miles Davis’s quintet.

“I have chills remembering his virtuosity that first day in the studio in New York,” she told me when I asked her about working with Carter during an interview for Uncut magazine in 2020. “He understood that less is more and the importance of the silence between the notes. He was also humble and open to my musical thoughts and suggestions. Our synergy is what you hear on ‘Compared to What’ and ‘First Time’.”

Like Nina Simone, Flack had begun her musical career in the hope of becoming a classical pianist, but fate took them both in a different direction. Simone carried the sense of having been unjustly thwarted with her throughout her life. I asked Flack if she’d ever felt that way, too.

“Life can be so unpredictable,” she said. “One thing I know is that everything changes. I’ve tried to embrace the twists and turns that life’s changes have brought. I took my classical training and used it as the foundation on which I based my arrangements, my dynamics and ultimately my musical expression. I think if you’re rigid about how you see yourself and if you aren’t open to the changes that life brings you, the resentment will show in your music and can interfere with honest expression.”

I’m listening to First Take while writing this. Whether it’s in the quietly spine-tingling gospel of “I Told Jesus”, the laconic protest soul of “Tryin’ Times” or the sublime sophistication of “Ballad of the Sad Young Men”, honest expression from a great artist is what you get.

* The photograph of Roberta Flack at Ronnie Scott’s in 1972, with Eric Gale (right), was taken by Brian O’Connor. If you want to read more about Ms Flack, you won’t find anything better than this piece by Ann Powers: https://www.npr.org/2020/02/10/804370981/roberta-flack-the-virtuoso