Monday at the Cockpit

I was pretty horrified over the new year to see, in the guides to the arts in Britain in 2025 produced by the Guardian and The Times, no mention at all of anything that might be happening in the world of jazz. Both papers have a long tradition of covering the music in an informed way, but that seems to have been set aside by the current generation of arts editors.

It’s more than a pity, particularly at a time when jazz, although its household names have gone, is showing such vitality at all levels, and particularly among a younger generation. That was an unmissable feature of Monday’s Jazz in the Round gig at the Cockpit Theatre, not just among the musicians taking part but in the audience.

Sure, the usual jazz listeners with decades of experience were well represented. But there were also lots of people of student age, a few with instrument cases, settling on the tiered benches surrounding the players on all sides. Some of them were obviously friends of the pianist Emily Tran’s very spirited quintet, featured in the opening slot nowadays reserved for JITR’s Emergence new-talent programme, but they and the other younger listeners in the room effectively reinvigorated the whole ambiance.

After Tran’s group, its front line of alto saxophone and trombone recalling Jackie McLean’s Blue Note albums with Grachan Moncur III, came the Portuguese guitarist Pedro Valasco, 20 years a London resident, building loops and effects with his elaborate pedal board, exploring the sort of territory John Martyn might have entered, given a couple of extra booster rockets. And finally came Empirical, a long-established but perennially creative quartet, with Jonny Mansfield replacing Lewis Wright at the vibraphone.

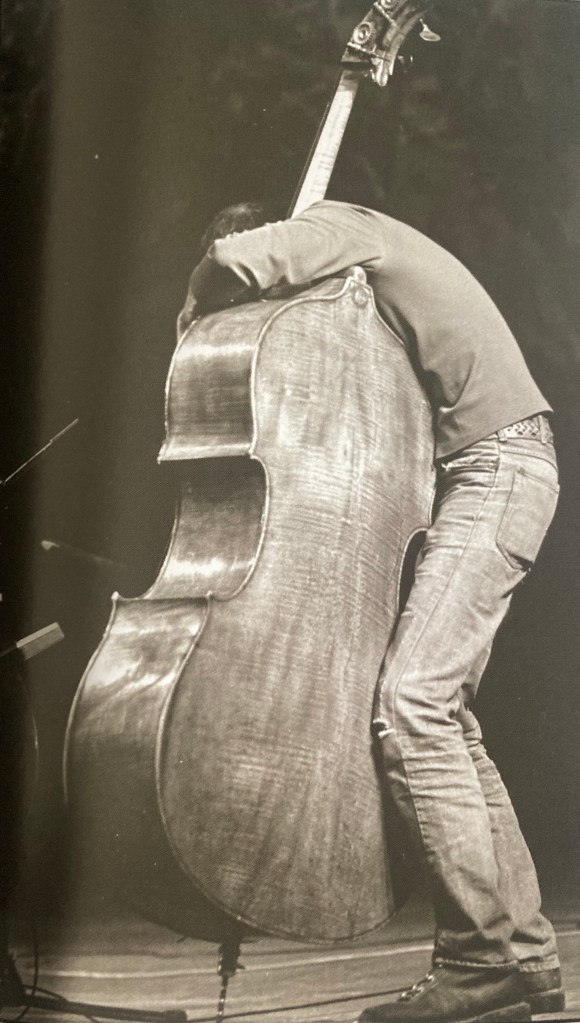

I’ve said before that Jazz in the Round is my favourite live listening environment, and during Empirical’s set there was a good example of why that might be. It happened while Shaney Forbes was carefully unfolding a drum solo on “Like Lambs”, his own composition, against overlapping rhythm patterns played by Mansfield, altoist Nathaniel Facey and bassist Tom Farmer in what sounded like three different time signatures.

Suddenly Forbes’s concentration was abruptly broken when the bass-drum beater flew off its pedal, landing at the feet of the front row. In many decades of watching drummers, I don’t think I’ve ever seen that happen before. Anyway, the nearest member of the audience was able to lean across and hand it back to the drummer, who quickly refitted it and screwed it up tight while the other three maintained their patterns without disruption, before resuming his train of thought and taking it to a conclusion.

There was, of course, a special roar of applause when the piece ended, but that in itself is not unusual for Empirical. Their music is complex, and sometimes knotty, but they consistently engage their listeners’ emotions in a straightforward way which demands a response. That in itself is quite unusual in this kind of jazz. You could analyse what they do in terms of pacing and projection but there never seems to be anything calculating about it.

They have the spontaneity that is the propellant of jazz and the warmth that is its lubricant, qualities for which Jazz in the Round, programmed and presented by Jez Nelson and Chris Phillips, provides a consistently rewarding environment.