Autumn books 4: Up and down in Croydon

By the time I first set eyes on Croydon, in the opening week of 1970, it had already achieved its new status as the symbol of high-rise architecture in Britain. To one who had yet to visit America’s big cities, it was an extraordinary sight. Amid the tower blocks and the urban motorways, I got lost and thus missed a big chunk of the Soft Machine’s first set at the Fairfield Halls. The venue itself was worth the visit: a monument to postwar modernism, opened eight years earlier.

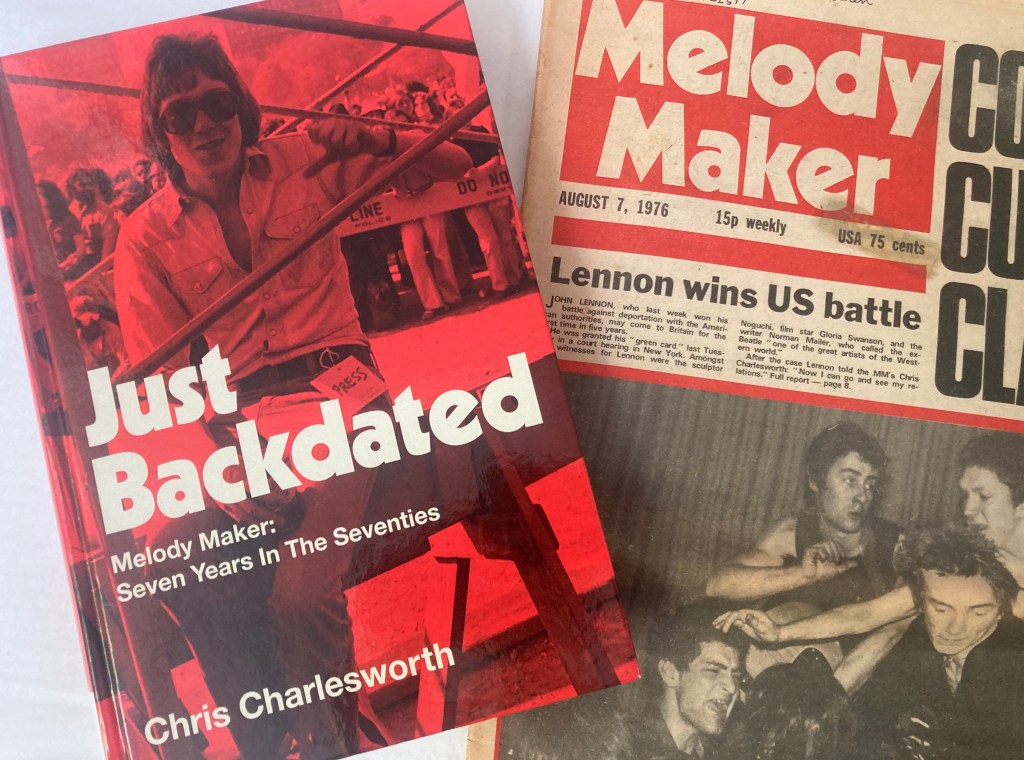

The second time I made my way through South London to Croydon — and the last, as far as I remember — was just under two and a half years later, when I went to the Greyhound pub to see Roxy Music supporting David Bowie. Because it was Roxy I wanted to see on June 25, 1972, and since they were on first, I was on time. It was nine days after the release of their debut album, and also of Bowie’s The Rise & Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars. I’d been to some of Roxy’s recording sessions at Command Studios in Piccadilly, and I wanted to see how the songs sounded live. (I stayed to hear Bowie and his band, but I’m afraid the songs and the presentation didn’t interest me much, and still don’t.)

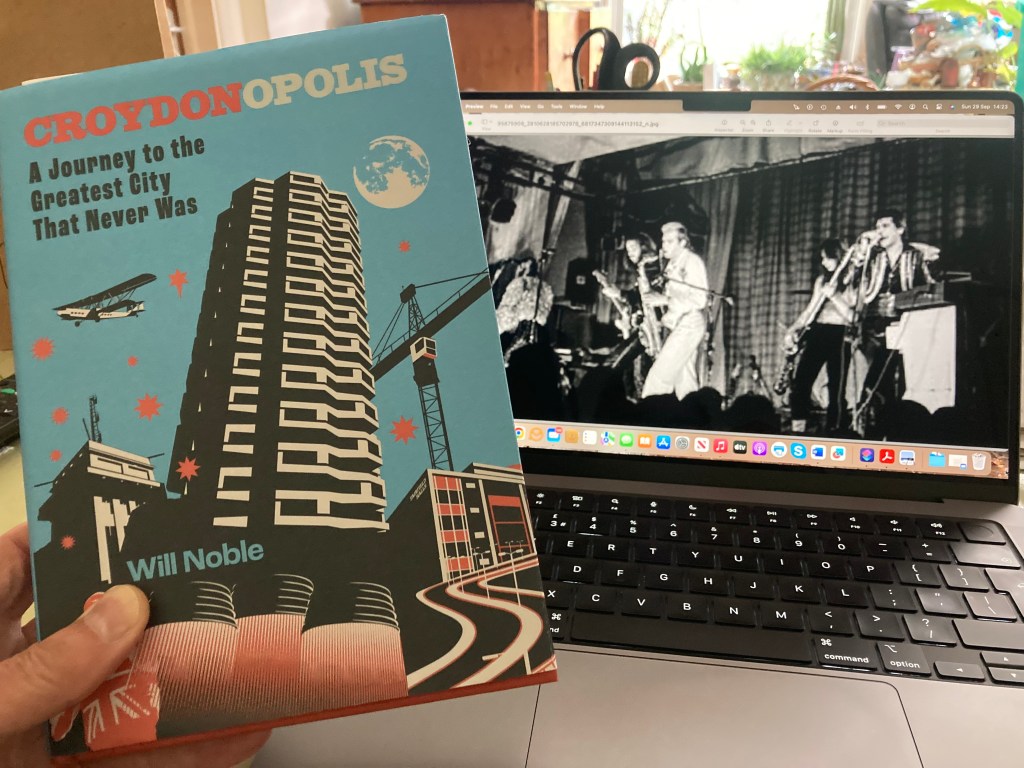

Croydon’s close links with popular music form one of the themes of a new book by Will Noble, the editor of the Londonist website. Croydonoplis: A Journey to the Greatest City That Never Was tells the story of a place whose initial renown came as the location of Croydon Palace, first erected as a manor house more than a thousand years ago as a staging post for the Archbishop of Canterbury on his journeys from Canterbury Cathedral to his London residence, Lambeth Palace. The present Croydon Palace was mostly built in the 14th and 15th centuries.

The place has a surprisingly rich history. Elizabeth I visited several times a year, for the horse racing. In the 19th century it had a popular spa and a pleasure park (where Pablo Fanque — remember him? — walked the tightrope). It became a railway hub, its population increasing as a result from 5,700 in 1801 to 134,000 in 1901. In 1928 it became the location of the original London airport, where a well appointed terminal featured the world’s first airport shop. And although those postwar towers were built for offices, a large part of the town’s history has to do with entertainment, from medieval fairs and variety theatres to the era of the Fairfield Halls and the Greyhound.

The great actress Peggy Ashcroft was a local product, as were the film director David Lean, the black classical composer Samuel Coleridge-Taylor, and Francis Rossi of Status Quo. There were many theatres, at which Louis Armstrong, Paul Robeson, Ella Fitzgerald, Gracie Fields, Bill Haley and Buddy Holly all performed. Bernstein, Boulez, Boult conducted at the then-new Fairfield Halls, as did Stravinsky. The American Folk & Blues Festival concerts featured Muddy Waters, Sister Rosetta Tharpe, Lonnie Johnson, Big Mama Thornton and Howlin’ Wolf. Ornette Coleman made his British debut there with a famous concert in 1965 (where a sceptic shouted “Now play ‘Cherokee’!”), followed 10 years later by Kraftwerk.

Malcolm McLaren studied at Croydon School of Art, as did Bridget Riley and Ray Davies, although McLaren’s Sex Pistols were banned from the Greyhound because the promoter didn’t like the idea of gobbing. Captain Sensible and Rat Scabies of the Damned first met at the Fairfield Halls, where they were cleaning the toilets. Croydon also the location of the Brit School, the alma mater of Amy Winehouse, Katie Melua, Adele, FKA Twigs, Jessie J and Kae Tempest. Most recently, it’s been the breeding ground of Dubstep and Grime, via local boy Stormzy and Rinse FM.

The tale of how Sir James Marshall, a former mayor and the chairman of the town planning committee, looked at the wartime bomb damage and dreamed up the idea of rebuilding the place in a very different form is extremely absorbing and well told, starting with the notion that the scheme was conceived as a response to the refusal in 1954 by the recently crowned Elizabeth II to grant Croydon the much-coveted city status. The vaulting ambition, the collateral damage and the ultimate failure of Marshall’s dream make for a fascinating read, even if you’ve only been there twice. Or not at all.

* Will Noble’s Croydonopolis is published by Safe Haven Books.