The timekeeper of Damascus

Intrigued by the title of Pat Thomas’s new album of solo piano music, The Solar Model of Ibn al-Shatir, I did a bit of online research into its source of inspiration. Born in Damascus in 1304, Ibn al-Shatir studied astronomy in Cairo and Alexandra before returning home to become the official timekeeper of the city’s main Umayyad Mosque. His extensive research into the relative movements of the sun, moon and planets enabled him to publish findings that represented an advance on the discoveries made in Ancient Greece and Egypt by Aristotle and Ptolemy, furthering a science whose subsequent luminaries included Copernicus and Newton. He died in 1375.

It’s hard to grasp now the eminence of such a figure in a world before clocks, a world of astrolabes and equants and epicycles. Al-Shatir designed a sundial for one of the minarets of his mosque — an engraved slab of marble 2m tall and 1m wide — and was responsible for determining the hours of the five daily prayers and the dates of the beginning and end of Ramadan. If you look online, you’ll find diagrams and calligraphy of great beauty.

He would probably have had interesting conversations on heliocentric matters with Sun Ra, another source of inspiration for Thomas, who was born in the UK in 1960 to music-loving parents from Antigua and is based in Oxford, from where he has worked with countless distinguished improvisers, notably the vibes-player Orphy Robinson in their shape-shifting group Black Top. Although Thomas decided he wanted to play piano as a small child after seeing Liberace on TV, and then adopted Oscar Peterson as an early model, today he belongs in a loose tradition of jazz pianists that includes Ellington, Monk, Herbie Nichols, Elmo Hope, Hasaan Ibn Ali, Dick Twardzik, Cecil Taylor, Andrew Hill, Muhal Richard Abrams and two Alexanders, von Schlippenbach and Hawkins.

The titles of the individual pieces also throw up some interesting information. “The Oud of Ziryab” refers to the 9th century Arab musician, born in Baghdad, who added a fifth pair of strings to the oud and spent most of his life in Al-Andalus, running an influential music school in Cordoba. “For George Saliba” salutes a contemporary academic, a professor at Columbia University and an expert on Arabic astronomy. “For Ibn al-Nafis” refers to a 13th century native of Damascus, an expert in law, literature theology and human anatomy who was the first to identify the way the blood circulates from the heart. “For Mansa Musa” is a dedication to a 14th century ruler of the Malian Empire, a man of enormous riches who famously went on an improbably lavish hajj in 1324-25, during which Musa allegedly built a mosque every Friday, wherever he stopped along his 2,700-mile route to Mecca.

That’ll do for the history lesson, although it might be enough to suggest how little those of us educated in the West actually know about the history and achievements of the Islamic world. What about the music? There’s nothing programmatic about the compositions and improvisations, in the sense that you could listen to them and remain unaware of any of the above associations. But I find it extremely stimulating, not least for the way that Thomas makes the piano sound very different: it sounds like wood and steel, and like something being struck. Not exactly “eighty-eight tuned drums” — a phrase generally attributed to Val Wilmer, although she’s not sure she coined it — but still very distinctive.

Thomas’s playing is marked by its clarity and control, even in the most intense moments. It’s rhythmically charged without being oppressive, and the counter-movement of his hands is often very compelling — sometimes reminding me, unlikely as it may seem, of Lennie Tristano in the mode of his “Descent into the Maelstrom”, a startling 1953 solo improvisation prefiguring Cecil Taylor’s flight from convention.

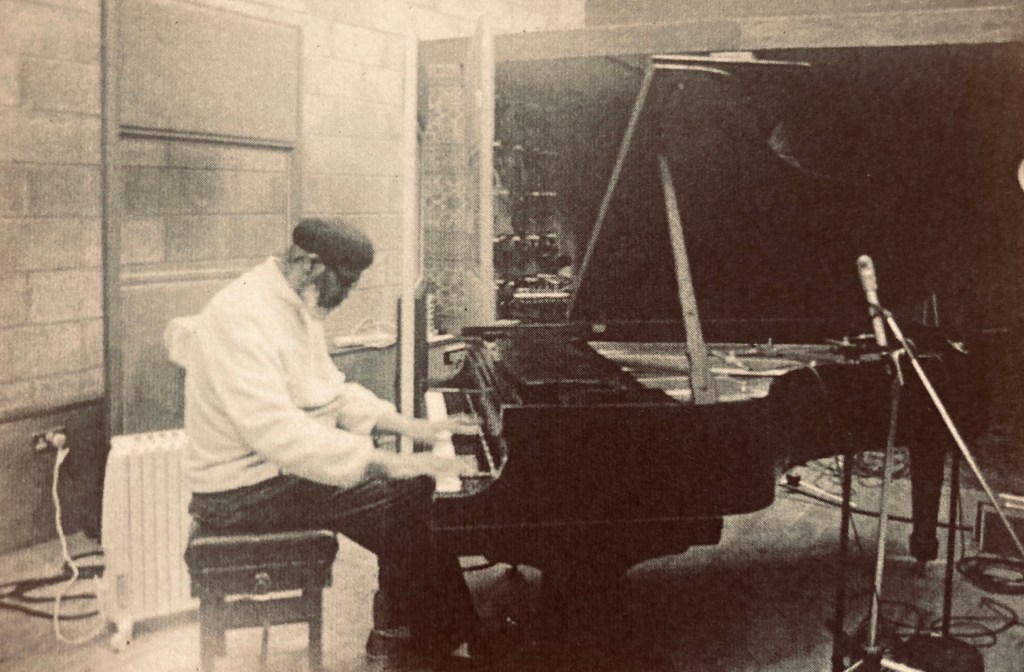

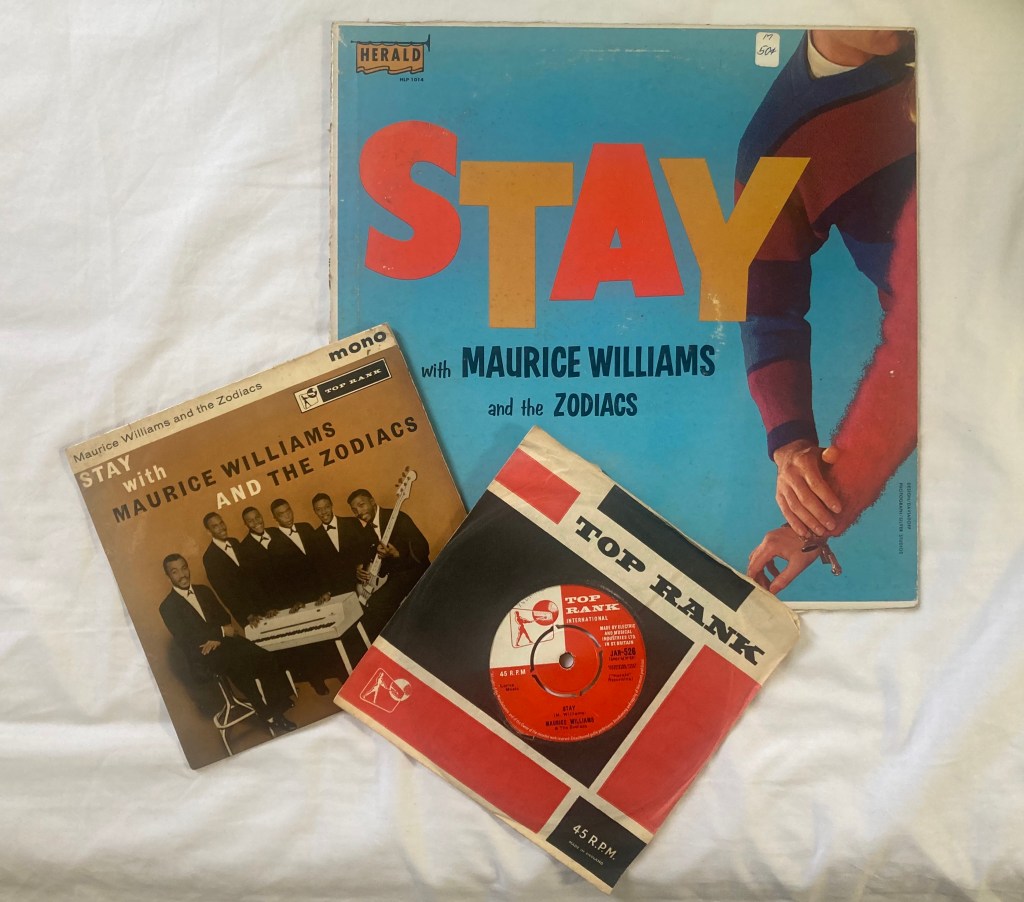

Thomas’s album is a follow-up to The Elephant Clock of Al Jazari, recorded at Café Oto in 2015 and released last year, inspired by a water clock devised in what is now Northern Iraq in the early 13th century by another visionary of the Islamic world. I don’t know whether Thomas intended these new pieces, recorded at the Fish Factory studio in North London on a single day in March of this year, to suggest the work of measuring movement of time in the world before the 17th century invention of the pendulum clock, but they certainly suggest something, though, even though it’s hard to pin down.

But however much or however little the listener cares to delve into the background of Thomas’s pieces, his high-tension creativity, his balance of contrast and continuity, and on this occasion his ability to coax an unusual timbre from the instrument make the album a very absorbing experience.

* Pat Thomas’s The Solar Model of Ibn al-Shatir is out now on the Otoroku label: https://patthomaspiano.bandcamp.com The photograph, taken during the session at the Fish Factory, is from the album cover and was taken by Abby Thomas.