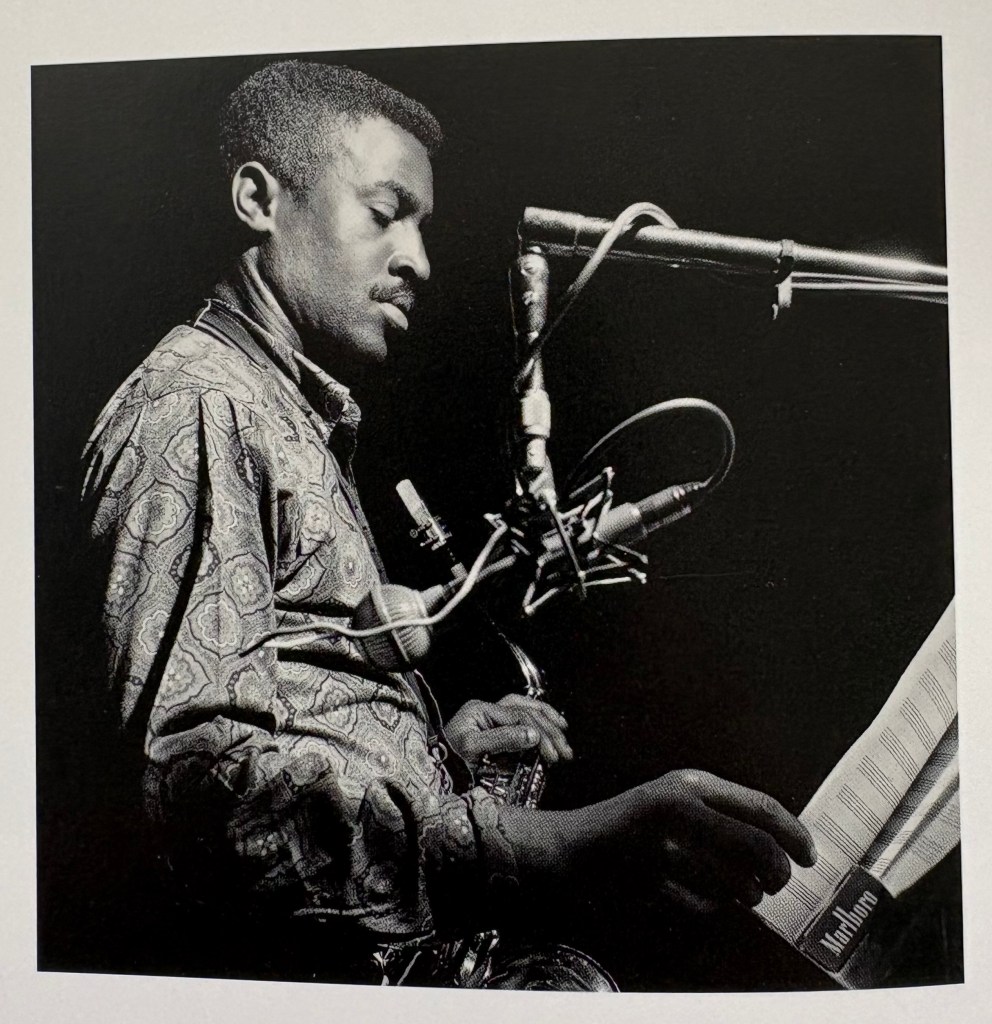

One of the things I loved about the Blue Note label in the early ’60s was its founders’ appreciation of the sort of basic, blues-rooted jazz to be found in the black clubs of the era, almost always featuring a Hammond organ, a guitar and a tenor saxophone. Jimmy Smith, Grant Green and Stanley Turrentine would be the most obvious examples of successful Blue Note artists in that genre, but I was also beguiled by the ones that didn’t reach their level of sales and celebrity. – or indeed, as in the case of a tenor player named Fred Jackson, any celebrity at all.

Jackson was brought to the label by his fellow tenorist Ike Quebec, who, as well as recording albums of his own, was then also functioning as Blue Note’s A&R man. Jackson made his Blue Note debut on the organist Baby Face Willette’s Face to Face in January 1961; twelve months later he recorded his own album, released later in 1962 under the title Hootin’ ‘n Tootin’. In 1963 and ’64 he appeared on two albums by another organist, ‘Big’ John Patton: the wonderful Along Came John in 1963 and The Way I Feel in 1964.

And that was it. After the session for the second Patton album, on June 19, 1964, Jackson disappeared completely and permanently from the radar screen. Nothing is known about his subsequent life (or, perhaps, death — were he still alive, he would be in his mid-nineties now).

All that we know about him is that he was probably born in 1931, probably in Atlanta, Georgia, and that at the time he recorded for Blue Note he was a member of Lloyd Price’s orchestra, through whose ranks — as with Ray Charles’s band — many fine jazz musicians passed (including John Patton). Jackson was one of those players who could switch with ease between R&B and modern jazz.

The available evidence suggests that he wasn’t what you’d call a great player, merely a very good one. But I’ve always been fond of Hootin’ ‘n Tootin’. It’s the sort of thing I remember one American critic describing as “meat-and-potatoes” jazz: no frills, no trimmings, no culinary experiments. Jackson’s accompanists are the guitarist Willie Jones, the drummer Wilbert Hogan, and, most interestingly, the Detroit organist Earl Van Dyke, best known in his role as a key Motown session man in the 1960s. How he came to be with Jackson at Rudy Van Gelder’s studio in Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey on February 5, 1962 has never been explained, but it’s nice to hear the hero of soul music favourites like “All For You” and “6 by 6” in the sort of setting he would have known extremely well from countless gigs in his hometown bars.

The programme consists of seven Jackson compositions, for which the term “originals” would be misleading: they’re mostly variations on the contours of better known jazz tunes, things like Milt Jackson’s “Bags’ Groove” and Nat Adderley’s “Work Song”. This is what was then known as “soul jazz”, full of gospel phrases strained through the bebop format, emphasised by the sound of the Hammond, which started its life as a church instrument. Jackson has a strong tone, a little hoarse at times, not as immediately identifiable as other Blue Note tenorists (Turrentine, Don Wilkerson, Hank Mobley, Wayne Shorter). His solos are always to the point and, as in the slow blues “Southern Exposure”, fit the mood beautifully.

Very much the sort of music that belongs in places with names like the Flame Show Bar and the Thunderbird Lounge, accompanied by the sound of background chatter and clinking glasses, cutting through a fog of cigarette smoke, it’s all well executed and perfectly enjoyable. But when the producer Michael Cuscuna came to reissue the album on CD in 1997, in Blue Note’s Connoisseur series, he was able to raid the archives for seven tracks recorded two months later, for which the same line-up was augmented by the addition of the great bassist Sam Jones, whose previous work for Blue Note had included an appearance on Cannonball Adderley’s classic Somethin’ Else in 1958. And those seven tracks, intended to form a second album, tell a slightly different story.

Perhaps it’s the presence of Jones, or maybe Quebec and the Blue Note co-founder and producer Alfred Lion asked Jackson for more variety. Whatever the stimulus, these seven compositions move into adjacent territories, including straight bebop on “Stretchin’ Out”, where Jackson proves his mastery of that most demanding idiom, delivering a fluent and well argued solo full of imagination and surprise. A lovely blues ballad called “Teena” is actually a barely disguised rewrite of “St James’ Infirmary”, a neatly arranged version of “Joshua For the Battle of Jericho” is retitled “Egypt Land”, and a medium-up 12-bar called “On the Spot” together make this session a more varied and sophisticated affair. An unidentified percussionist on two Latin-inflected tracks might be Garvin Masseaux, who played the shekere on Quebec’s album Soul Samba a few months later.

According to Cuscuna, Alfred Lion seems to have concluded that 35 minutes of music was not enough to make an album (although Hootin’ ‘n Tootin’ was only a minute or two longer). More likely is that the first album didn’t achieve enough sales to justify a follow-up. Blue Note often did well with 45s aimed at jukebox and radio play (such as Patton’s “The Silver Meter” and Lee Morgan’s “The Sidewinder”), but I can find no reference to a 45 extracted from Jackson’s first album (** I’m wrong — see Comments).

Hootin’ ‘n Tootin’ is getting another reissue this spring, in Blue Note’s Tone Poet series, which features the original album in remastered 180g vinyl form, encased in a gatefold sleeve with extra session photos by label’s other co-founder, Francis Wolff, who had a way of lighting musicians that turned them — and their button-down shirts and heavyweight shawl-necked cardigans — into after-hours icons. The latest reissue won’t have is those extra seven tracks, which give a broader view of Fred Jackson’s gifts. But whatever his unknown fate, it’s nice to see him back in the catalogue.

* The photo of Fred Jackson was taken during the Hootin’ ‘n Tootin’ session and is included in The Blue Note Years: The Jazz Photography of Framcis Wolff, published by Rizzoli in 1995. The Tone Poet reissue of the album is released on April 3.