The story of Sandy Denny

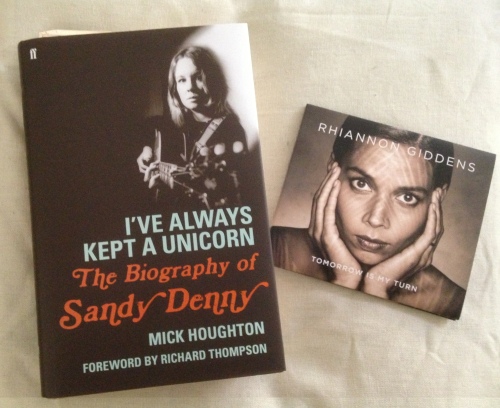

I’ve been listening to Rhiannon Giddens’ new solo album, Tomorrow Is My Turn, while reading Mick Houghton’s just-published biography of Sandy Denny, I’ve Always Kept a Unicorn. Not at the same time, you understand, but it’s an interesting and salutary juxtaposition.

I’ve been listening to Rhiannon Giddens’ new solo album, Tomorrow Is My Turn, while reading Mick Houghton’s just-published biography of Sandy Denny, I’ve Always Kept a Unicorn. Not at the same time, you understand, but it’s an interesting and salutary juxtaposition.

Tomorrow Is My Turn is almost scary in the perfection of its settings for Giddens’ treatment of blues, folk, country and gospel songs. As a producer of this kind of material, T Bone Burnett offers a guarantee of empathy: a mandolin here, a fiddle there, a banjo where needed, a touch of horns, a subtle wash of strings, all applied with the greatest sensitivity to an exquisite choice of material. It’s one of the year’s essential purchases, a huge step forward for a singer whose work with the Carolina Chocolate Drops had already established her credentials as an interpreter of roots music. She’s a very fine singer, and she deserves this treatment. You find yourself nodding your head in admiration as she copes so elegantly with the various idioms (even French chanson: check the poised understatement of her version of the Charles Aznavour song that gives the album its title).

Sandy Denny, however, was not merely a fine singer: she was a great one. Not only were her tone and phrasing lovely and distinctive, but she sang from the inside of a song and she had the gift of slowing your heartbeat to match the pulse of her music. What she didn’t possess were the attributes that seem to be propelling Giddens to a higher plane: a powerful sense of focus, a rock-solid self-confidence, and the right team around her at the right time.

I knew Sandy a little, and even 37 years after her death I found reading I’ve Always Kept a Unicorn an extremely distressing experience. Mick Houghton is not a dramatic writer, but he doesn’t need to be: he just needs to stitch together, with quiet diligence and the aid of fresh testimony from many of her surviving friends and colleagues, the story of how Alexandra Elene MacLean Denny, born in Wimbledon in 1947, achieved recognition without managing to build the sort of career that everyone expected her to have, and then fell so fast and so conclusively that she was dead at 31.

Two linked episodes — the aftermath of Fairport Convention’s motorway tragedy and the saga of Fotheringay — stand out as pivotal. One night in May 1969 the van carrying members of Fairport Convention back to London from a gig in Birmingham crashed down an embankment on the M1, killing Martin Lamble, their drummer, and Jeannie Franklyn, the girlfriend of Richard Thompson, their lead guitarist. The traumatised band recruited a new drummer, Dave Mattacks, and a fiddler, Dave Swarbrick, and threw themselves into a different kind of project: the album Liege and Lief, in which they applied rock-band techniques to traditional material. It was released in December of that year, and its instant critical acceptance as a benchmark in the evolution of folk-rock diverted them from the musical path they would surely have followed had the accident never happened and the fast-evolving songwriting of Sandy and Richard remained the core of their activity.

Eventually the pair left in frustration, both keen to stretch their wings. Sandy put together the five-piece Fotheringay in 1970 with her new boyfriend, the Australian singer/guitarist Trevor Lucas. Joe Boyd, who had mentored and produced the Fairports, firmly believed that Sandy’s future was as a solo artist, not as a member of another group — particularly not one organised, as she insisted, along strictly democratic and non-hierarchical lines. He distrusted the charismatic but headstrong Lucas, and he was appalled by the way the record company’s large advance — originally predicated on a solo album — was being blown on such things as an oversized PA system and a Bentley in which they made their way to gigs.

But although Fotheringay’s first album, and their uncompleted second effort, may have been recorded under Boyd’s disapproving gaze, out of those sessions came the finest moment of Sandy’s career. Within the highly original and starkly dramatic arrangement of “Banks of the Nile”, a traditional ballad telling the story of the reaction of a young girl to the imminent departure of her soldier lover, Sandy seems to summon centuries of English history. As the singer Dick Gaughan said on the subject, in an eloquent note in the booklet accompanying A Boxful of Treasures, the five-CD anthology released by Fledg’ling Records in 2004: “The raw, aching agony which she brings to her reading of it makes it impossible not to feel the fear and grief of the young woman at the separation from her loved one and the uncertainty of his return from the horrors of war . . . It is the supreme example of the craft of interpreting traditional song and is the standard every singer should be aiming for.”

Sandy didn’t write “Banks of the Nile”, but she did write “Who Knows Where the Time Goes”, “Late November”, “John the Gun”, “It’ll Take a Long Time” and other songs that showed her gift for taking a sudden but invariably graceful left turn with a melody or finessing an unexpected chord change with perfect logic, and for lyrics that often contained affectionate but clear-eyed portraits of friends and fellow musicians (Anne Briggs in “The Pond and the Stream”, for example, or Richard Thompson in “Nothing More”). But “Banks of the Nile” indicates most clearly what might have been, had a combination of internal and external pressures not provoked the disintegration of Fotheringay after less than a year, thus denying her the chance to remain a member of a sympathetic and settled unit whose collective musical ambition matched her own.

Chronic insecurities were beginning to hinder her career, particularly after the rupture with Boyd, which removed a provider of support and decisiveness. The biggest blow to Fotheringay was dealt by the Royal Albert Hall concert of October 1970. Disastrously, they invited Elton John to open the show, at the very moment when his career was taking off. He hadn’t yet grown into his full on-stage flamboyance, but his performance was powerful enough to put his hosts in the shade. When they came out after the intermission, it was somehow like the colour on a TV set had been suddenly turned off — and the audience, which had come to acclaim Sandy and her band, found themselves present at an epic anti-climax. Three months later, demoralised by that event and by the unsatisfactory sessions for their projected second album, the band broke up — thanks largely to a simple misunderstanding between Sandy and Joe Boyd over the terms on which he would produce her first solo effort.

In fact Boyd never produced her in the studio again, and the four solo albums released between 1971 and 1977 chronicle a diminishing ability to identify and present the essence of who she really was. The overproduced (by Lucas) cover version of Elton John’s “Candle in the Wind” on the final album, Rendezvous, represented some sort of nadir. The record company — Island — did its best, which too often turned out to be not so good. She found herself agreeing to be photographed by David Bailey, to be dressed up in a 1930s costume, and to be airbrushed and wind-machined in an effort to create an image more superficially glamorous than that represented by her own true self. As Island grew too quickly and had its head turned by success, her career became, to some extent, collateral damage.

When she was voted Britain’s top female singer by the readers of the Melody Maker not once but twice, in 1970 and 1971, it was assumed that commercial success would take care of itself. But after Boyd, she didn’t get much constructive help — for which, now, I must partially blame myself, since I was running Island’s A&R department between 1973 and 1976. But the artists inherited from Boyd’s Witchseason stable were somehow thought to be a law unto themselves in terms of musical direction, and although Sandy was loved within the company for her warmth of her personality as well as for her artistry, she was not biddable. Nor, in those days, were real artists supposed to be.

Houghton doesn’t slow up the narrative by spending much time describing the music, but he does make some discreetly perceptive observations. He remarks that Sandy’s first solo release, The North Star Grassman and the Ravens, is “the only album on which Sandy steadfastly stands her ground — usually by the seashore or the riverbank — and invites her audience to come to her.” And he writes of Trevor Lucas, five years later, working on the production of the ill-starred Rendezvous, “doing such protracted overdubs that it was almost as if he was subconsciously trying to bury the sentiments of the songs.”

Although delving deep into her turbulent love-match with Lucas and the increasing dependence on drugs and alcohol that accompanied her decline, he treads lightly when it comes to other, deeper-lying factors that might be held partially responsible for her unhappiness, such as an enduring fretfulness about her looks (particularly her weight) and an apparent history of abortions and miscarriages. Some readers may feel that the significance of these matters looms larger than the author allows himself to suggest. Eventually, in 1977, she would have a child with Lucas, a girl whom the father found it necessary to kidnap and take off to Australia less than a year later, as Sandy’s problems worsened. Four days after their unannounced departure she was found unconscious at the foot of the stairs at a friend’s flat in Barnes, and died in hospital a further four days later.

It’s a shock to realise that someone you knew has now been dead for longer than they were alive. Had she lived, she would have turned 68 a few weeks ago. Perhaps in that time she’d have encountered another manager, producer or A&R person capable of earning her trust, focusing her talent, nurturing the elements that made her unique, and presenting them to the world in the right package — the kind of package that Rhiannon Giddens seems to have been granted in 2015. Who knows how much great music was left in her? I like to think of Sandy coaxing Anne Briggs out of seclusion and inviting Kate Rusby to join them both on stage.

Houghton’s scrupulously fair account of her life makes it clear that she could be difficult and destructive, but allows those who knew her well to remember another side. The drummer Bruce Rowland — who had replaced Dave Mattacks in the Fairports by the time she recorded a last album, Rising for the Moon, with the band in 1975 — touchingly calls her “endlessly forgivable”. Her old folk-club mate Ralph McTell tells Houghton: “She would provoke — push people to the very limit at times, which sounds like she was a nasty person, but she wasn’t. People would take it because they loved her. I don’t know anyone who didn’t love her.” And you didn’t have to know her to love her. You only had to listen to “Banks of the Nile”.

* I’ve Always Kept a Unicorn is published by Faber & Faber. Tomorrow Is My Turn is released on the Nonesuch label.

Profound … touching, brilliantly written as usual – thanks Richard

Hi Richard. An excellent piece; I’ve just shared it on Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/EyeLevelwiththeStylus/posts/452352941595492

Really enjoy your writing.

Very interesting (& moving) tribute. The view from Island Records is fascinating. I agree about Giddens CD: the setting of Last Kind Word Blues, with a fuzz guitar in the left channel and a mandolin in the right, is sublime and her vocal has an ancient depth. As for Sandy’s greatest recording. For me, it was A Sailor’s Life on Unhalfbricking. Her vocal combining poise and possession is borne aloft by the raga-rock improvisation of Thompson and Swarbrick. One of the greatest things ever recorded imho.

Thanks. Very revealing for someone as myself, a big Fairport and Sandy Denny fan in those days without knowing a single thing about Sandy the person. I saw Fotheringay and Fairport perform in Rotterdam at the first Dutch music festival in 1970. I still listen to Liege and Lief occasionally. It still holds it’s own after all these years. Sad story of a fantastic singer. Sometimes it almost seems par for the course.

Ivor Williams

Lovely piece Richard, Liege and Leaf may well be Island’s greatest album.

Nice piece Richard. I’m in cahoots with the praise of LIEG AND LIEF, a real wonder of an album. Same goes for NORTHSTAR and parts of Sandy’s other solo stuff.

“…she had the gift of slowing your heartbeat to match the pulse of her music.” Indeed.

Haven’t heard Fotherigay. I will hear Rhiannon Giddens when her new one arrives here in a few days. Thanks.

Completely disagree with almost all of this. Sorry. I’ve just listened to Rhiannon Giddens’ album and its not for me; I think these days that T Bone Burnett’s influence on recording is like that of Chet Atkins in an earlier era; proficient, skilled even but ultimately without a trace of soul. Whatever modern music is or might aspire to, this ain’t it as far as I am concerned.

I thought Sandy Denny was seriously overrated; could never understand how she kept winning the Radio 2 Folk Award. Thin, reedy voice. June Tabor could run rings around her, as could say, Lal Waterson, Shirley Collins and my own favourite, Niamh Parsons. I haven’t read the book, the biography that you refer to and it is interesting that you found it an extremely distressing experience. Received wisdom is that she was mistreated by every man she met; not least by Mr Boyd. Were you one of those men, Richard?

I don’t think so, Mr Kikarin, and I don’t see what grounds you might have for making such a suggestion.

Re the music: You’re perfectly entitled to your opinions, of course, and I have a sneaking sympathy for your view of T Bone Burnett’s work, but the notion that Sandy’s voice was “thin” and “reedy” is simply bizarre.

I too have read Mick’s book – well, the last two thirds of it so far. He is indeed a weaver of lightly-touched threads and I think the book succeeds as much because of Mick’s deft style as the content of the painstakingly collected testimony he presents.

I agree totally, Richard, that ‘The Banks Of The Nile’ is her finest moment. I’m still mulling over other questions, though: like whether she has, perhaps, been overrated in recent times because of the finite nature of her career and the tragedy around it. I just need to think of that awful gloopy ‘Candle In The Wind’ – in fact, even the very choice of recording ANY version of it – to feel that hers was a flame pretty much burned out by the end. I really struggle to see how she would have progressed through the chilly waters of the 80s into any kind of artistic renaissance in the later 90s or today.

I can vaguely imagine her, after 15-20 years without a record released, appearing in very nervous form on ‘Later With Jools’ promoting a comeback record on a small label, with a performance worthy enough to feel okay to old fans – of some new song with slow minor chordal movements and a rather more lived-in, narrower-range voice – but leaving everyone else wondering what the fuss was about. Like seeing or hearing Marianne Faithful or Bonnie Dobson, say. Or, indeed, hearing the once great Shelagh McDonald now (a beautiful singer who made two albums on B&C in the early 70s then ‘disappeared’ for nearly 40 years) – there’s a tolerable shadow there, but it isn’t the same. It can’t be. There might be something there, of any imaginary Sandy comeback after a long wilderness, to add a coda to a story – but the story had to be there first. Mojo would run a feature; the Guardian too; Will Hodgkinson would try and squeeze a Times three star up to a four for old times’ sake. Everyone would try and forget the (likely) half-baked attempts at comebacks in the Putney Half Moon during the intervening 20-odd year (a genuine wilderness is better for a story than a bumbling series of half empty pub gigs.) I just can’t see any really happy ending, from a purely artistic point of view.

But in a way this would be academic because, as Mick’s book suggests – the way I read it, not down to any position he himself takes (that magical light touch again) – she was so dreadfully flawed as a person, with self-doubt and huge dependencies on chemicals and on people, that she couldn’t have coped with the way the music business changed. She seemeed to need such a colossal support network around her, even to get her onto a stage. She had her time, in a gentler and more forgiving era, and, brutal as it seems to say it out loud, I think she kind of blew it.

At least, if she *wanted* to be a fully-professional touring and recording artist presenting her own music to people – like Ralph McTell, for instance, who built a very solid career as a Brit with his own songs and as a reliable performer internationally – she blew it. But it’s not altogether clear that that *is* what she really wanted. One thing which comes across from Mick’s book throughout, from the late 60s Fairport era onwards, is that she didn’t like touring. The Fotheringay balance sheet must have looked awful – a handful of gigs over a year or so.

One of the biggest questions in any reader’s mind will, I suspect, be whether Trevor Lucas was a good or a bad influence on her. She seemed in thrall to him emotionally throughout the 70s – with emotional decisions trumping artistic and career ones – and yet the man was ‘amoral’, a vexatious philanderer, as seems widely to have been known by all and sundry at the time. (The question – which Joe Boyd has often focused on – of whether he was a good or bad influence in purely musical/artistic terms, especially in the old chestnut of whether she should have begun a solo career on the back of the MM poll wins instead of sinking time/money/personal profile into Fotheringary, is another one entirely. I’m not sure here… he certainly wasn’t a great talent, but when Fotheringay blend together as a band it *does* work really well, as the ‘Beat Club’ TV clips demonstrate.)

It seems to me that Island gave all the Fairport axis enough rope to either climb out of the canyon or hang themselves. It seems like a kind of louche golden age at Island where people got to make increasingly unsuccessful albums long after other labels at the time (or ANY label from the 80s/90s on) would have pulled the plug. I look at that ‘Bunch’ LP as a kind of totem to the rudderless self-indulgery of the era – be it from artists, label or both. The idea of a load of people good (but none yet commercially successful) in one field, ie the barely invented English folk-rock fraternity, getting together over a load of booze and drugs in Richard Branson’s studio for two weeks to bash out old 50s rock’n’roll encore jams and releasing it under a one-off name just seems to be madness on paper and largely cloying in practice.

Funnily enough, I still think Joe Boyd’s 4LP Sandy Denny box set selection from 1985 is the best distillation of her work. But I’ve been listening to the Fotheringay first album on CD a lot since reading Mick’s (thoroughly recommended!) book and I’m looking forward to the Fotheringay box set, having never heard the second album revamp nor the entirety of the Rotterdam and BBC material. Maybe it will definitively make the case of Fortheringay as her one great moment.

I suspect that, far from being able to coax Anne Briggs out of retirement in the 21st Century, Sandy wanted more than anything to *be* like Anne: to have the firmness of spirit not to be so needy with other people, nor so conflicted about a career in music. Annie wandered on the land… she made some recordings… she left the stage and got on with a better life. Anne Briggs truly beat the system. She was immune to its chimera. Whatever kind of life Sandy wanted, she just couldn’t find it.

Thanks for all that, Colin. An interesting hypothesis, but I prefer my optimism to your pessimism. And I think you’re unfair to The Bunch. It’s not a great album in any way but at the time it was refreshing to have a group of folk-rock royalty exposing their love of simple, primal rock and roll. That was its purpose, I think. Re Trevor Lucas: my belief is that it’s not as simple as “good” or “bad”. PS: “The Vexatious Philanderer “would have made a great title for a Fotheringay song…

Just for the record, excuse the pun, as a Buncher of old I remember it lasting one day not two weeks as Colin Harper suggested. It was just before Branson recorded Tubular Bells and over a kind of baronial supper in The Manor, he looked like a giant lizard about to eat the world. Which he did.

Oh, I suppose a tendency to pessism is my default setting. Which means that one is, of course, often pleasantly surprised! Who knows how things would have worked out if SD had lived… re: The Bunch – if I’ve got it wrong and it was one day not two weeks then it becomes a very fruitful session and not the drawn out, indulgent mess I feel sure I’ve read about somewhere (Linton’s book?). I wasn’t around at the time (well, I was just about in primary school) so I don’t have the perspective of the time, as Richard suggests, to perhaps appreciate it in context.

It’s interesting, isn’t it, how many English acts started performing old rock’n’roll covers around 1968-70 – the Who, Zeppelin, Fotheringay et al. Roughly the same time as The Wild Angels and the supposed ‘authentic’ r’n’r revival was going on. I’d love to read your reflections around that theme, Richard…

And Ian – I didn’t mean to in any way criticise your musicianship or those of anyone else involved in The Bunch. I just see it as one outcome of a rudderless, monied scenario that seemed to be going on around talented but (it seems to me) indulged people. Having said all that, I DO have a soft spot for Fotheringay’s encore recording of ‘Memphis Tennessee’. But ‘Let’s Jump The Broomstick’ on ‘North Star Grassman…’ was surely a bridge too far let alone a whole LP of the stuff.

For some reason, Ashley Hutchings revived the thing 20-something years later with a load of the same sort of people for an album called ‘A-Twangin’ And A-Traddin’. As I recall, it was just awful. But I’ve clearly got a vbit of a blind spot for folk-rockers doing ersatz r’n’r!

Don’t worry Colin, the Bunch sessions weren’t that good from what I remember. And you are right that the lure of glitz and big advances was a challenge for serious folk musicians. But rock ‘n roll was itself a kind of folk music with its own roots so I understand the desire to play it. I think Sandy was as much a misfit in showbiz as I was in the world of folkies but the late sixties was full of misfits. Probably why it was so creative and why I can’t remember much about it….

Maybe those English acts didn’t start performing old R&R covers around 68-70, maybe they had played them all the time, just like most of the people learning to play.

It might look like following a trend, when they did it “suddenly” in public, but some of them had “always” played them, as an encore or whatever..

And you can’t blame The Bunch for the (awful) Twanging of Mr. Hutchings

Colin Harper’s excellent comments surely point towards part of the enduring fascination of Sandy Denny: the Romantic chimaera of great talent and beauty prematurely snuffed out. The same reason that Ian Curtis and Gram Parsons continue to generate a mystique while more low key workman-like talents go unnoticed. Think Chatterton on his bed. Think Keats: “I have been half in love with easeful Death, Call’d him soft names in many a mused rhyme.”

Sandy’s friends may have found her ‘endlessly forgivable’ but that wasn’t my reaction at the time as an avid Fairport fan. The decision to depart just as Liege and Lief was gaining critical and commercial success appeared incomprehensible. Despite the magnificence of Banks of the Nile, Fotheringay seemed like a pale imitation, and Northstar ventured so far across the river that few people chose to join her. The later solo albums contained several memorable and highly accessible songs of course, but by then much of her original audience had stopped listening.

Given your original enthusiasm, I do think you’d find the book worth reading.

What seems astonishing to me is the speed that albums were recorded and released in those days. Sandy was only a member of Fairport from May 68 to Dec 69 and during that time they recorded their definitive albums Holidays, Unhalfbricking, and Liege & Lief, all, amazingly, released in 1969. It seems to be one album each decade these days.

Yet another masterful piece, Richard.

Sandy remains one of my favourite singers to this day. While I loved Judy Dyble’s contributions to the first Fairport album, the band certainly scaled the summit with Sandy and the next three records. A Sailor’s Life, She Moves Through The Fair, Fotheringay, Crazy Man Michael ….doesn’t get much better.

I do agree her own albums are somewhat patchy and that such a supreme talent deserved better. Though she never performed in Dublin I saw post-Sandy Fairport play several times and was lucky enough to see her and Richard at the Lincoln Folk Festival in July 1971.

Whatever her possible faults and self-inflicted “issues”, one can only imagine the pain she suffered on being separated from her young daughter by such a distance.

A Bentley? I remember them driving around Notting Hill in a big black six cylinder Austin Westminster but not a Bentley. Maybe that came later. Underneath I think these folk rockers were more rock than folk. On North Star Grassman Sandy and Richard T let rip as if released from their doom and gloom in Let’s Jump the Broomstick, the track I enjoy most on that album. I happen to know that album was fuelled on Westbourne Park Rd curry. Sandy could down a couple of bottles of Mateus Rosé in one meal. I always wondered if the Fairports music would have been different with a bit of lysergic in the drinks.

Ian — The legend says it was a Bentley. Print the legend.

Thanks for this, Richard!

Your piece is very insightful and much more than a book review.

The comments and reactions only add to this

Reblogged this on shensea.

I hesitate to interpose myself between august characters like Richard Williams and Colin Harper, but I lean towards Richard’s optimism as to what Sandy might have done if she’d lived.

I reckon she might have grown up a bit, left the brandy (and the poppers) on the shelf, split from Trev, and so on. At worst she could, as Linda Thompson has suggested, have checked herself into the Priory and dried out.

At her best, she radiated power; eg the Howff gig in 1973. People (including me) loved her for her voice, her writing and her personality. She might have benefited from a simple device which kickstarted the Cropredy Festival and others – the mailing list. Following on from that would have been the “long tail” created by the Internet which would have allowed her to make a successful career. I’m sure we would have seen her perform with people like Thompson and Swarbrick who would have done her justice musically – I noticed she was at her best when she had friends round her. Who isn’t? Apart from Mr. Dylan I guess.

Obviously “what ifs” are pretty futile – but given that most of us are still around after the excesses of the Sixties and Seventies, I see no reason why Sandy would not have sorted herself out. But not TOO much I hope……

Unlike

The History and Mystery of Music: Sandy Denny is being offered at the Saint Louis. MO Library, April 19th. A chance to exchange stories.