The spirit of 1971

On an earlier re-release of the first and only album by Centipede, the 50-strong (and therefore 100-footed) band assembled by Keith Tippett, RCA’s marketing department used a quote from the Melody Maker‘s original review: “No one who wants a permanent record of where our music was at in 1971 will want to be without Septober Energy.” It was true at the time and today, listening to a remastered and reissued version of the double album made by an ensemble containing actual and former members of Soft Machine, King Crimson, the Blue Notes, the Spontaneous Music Ensemble, the Blossom Toes, Nucleus, Patto, the Steam Packet and Dantalian’s Chariot, it still feels right.

In his notes to the new Septober Energy reissue, Sid Smith quotes my description of it at the time as “a miracle”, but as miracles go it was an eminently achievable one, given the spirit of creativity, goodwill and mutual encouragement in which it was conceived and implemented under Tippett’s inspired guidance. This was the first of his large-ensemble projects; if it lacked some of the finesse of later endeavours, it wanted for nothing in terms of spirit.

The clue was in the title. “Energy” was a word much applied back then to the kind of improvising habitually done by the freer players here — the tenorists Gary Windo and Alan Skidmore and the trombonist Paul Rutherford, for example, the singers Julie Tippetts and Maggie Nichols, and the three marvellous South Africans: the trumpeter Mongezi Feza, the altoist Dudu Pukwana and the bassist Harry Miller. But others from related fields were cheerfully infected by the same vibe: the trumpeter Ian Carr, the guitarist Brian Godding, the oboeist Karl Jenkins and the 19 string players led by the violinist Wilf Gibson. And then there were the horns from Tippett’s own sextet, already borrowed by Soft Machine and King Crimson: the cornetist Mark Charig, the trombonist Nick Evans and the altoist Elton Dean. There were five bass players in all, including Jeff Clyne and Roy Babbington, and three drummers, two of them being Robert Wyatt and John Marshall. Robert Fripp played guitar on stage and produced the album.

I seem to remember that the announcement of their debut concert, at the Lyceum in November 1970, made the front page of the MM. After that first gig, boisterously exhilarating but inevitably chaotic, they went on the road in Europe and had a great time. The following June they went into Wessex Studios in north London, located in an old church hall, with just four days for recording the 80-minute piece under Fripp’s supervision and a couple more days for him to mix and edit the results into four movements, each one fitting a side of the double album. Their last appearance was at the Albert Hall in December 1971.

All the enthusiasm of the time, as yet unspoiled by time and the depredations of the music industry, is there on the album. And so, thanks to the skills of the composer and the producer, is a clear view of the individual strengths of the featured soloists (meaning practically everybody), as well as their readiness to attempt a coalescence into something greater than the sum of the parts.

Part 1 begins with the sound of small percussion, like something from a Shinto temple, before long tones — strings, voices — emerge and hover, soon disrupted by the first hints of the storms to come. Gradually the brilliant disposition of the orchestral resources comes into focus as Tippett balances the roistering horns and thunderous drums with subtler deployments and great control of crescendo and diminuendo. The wrapover to Part 2 is a lovely bass conversation — one bowed, one plucked, one playing harmonics con legno — leading to a very period-correct jazz-rock sequence with Tony Fennell’s drums and Babbington’s bass guitar accompanying quarrelsome saxes over a brass choir, suddenly interrupted by giant overlapping unison riffs in which, metaphorically, the entire band seems to have been fed through a fuzz-box. A space is cleared for Carr’s serene trumpet and Skidmore’s urgent tenor to take solos against the rhythm section, both exploiting the lift of lyrical chord sequence, before Godding’s distortions announce the return of the heavy artillery. An improvised trombone quartet adds another contrasting texture.

Part 3 opens with the four singers — Tippetts, Nichols, Zoot Money, Mike Patto — delivering Julie’s lyric without accompaniment: “Unite for every nation / Unite for all the land / Unite for liberation / Unite for the freedom of man.” Then the trio of drummers take over for a powerful conversation, each individual carefully separated in the stereo picture, leading into a long ensemble passage that builds to a shuddering climax before a slow electronic fade leads to the two female singers improvising over the strings, like a giant version of the SME, the same forces combining in a disquieting written section that ends the side. Tippett’s solo piano announces Part 4, sliding into a broad, swelling theme for brass, mutating through a long Elton Dean soprano solo into a trenchant restatement of the “Unite for…” song, and ending with a pensive coda for piano and cornet.

Of course it sprawls, and not every note played over the course of almost an hour and a half could be described as deathless or essential. But it was and remains a triumph of conception and execution, a vision of musical scale with, as it were, the Little Theatre Club at one end and Woodstock at the other. It also set me thinking about the form an equivalent project might take today, with similarly open-minded and collaboratively inclined musicians drawn from newer generations. Jonny Greenwood and Thom Yorke from Radiohead would have to be there. Shirley Tetteh, Shabaka Hutchings, Olie Brice, Sheila Maurice Grey, Moses Boyd, Nubaya Garcia, Rachel Musson, Tom Skinner, Rosie Turton, Cassie Kinoshi and Theon Cross from the new London jazz scene. Beth Gibbons and Adrian Utley from Portishead. Keiran Hebden (Four Tet) and Sam Shepherd (Floating Points). Well, you can make your own list.

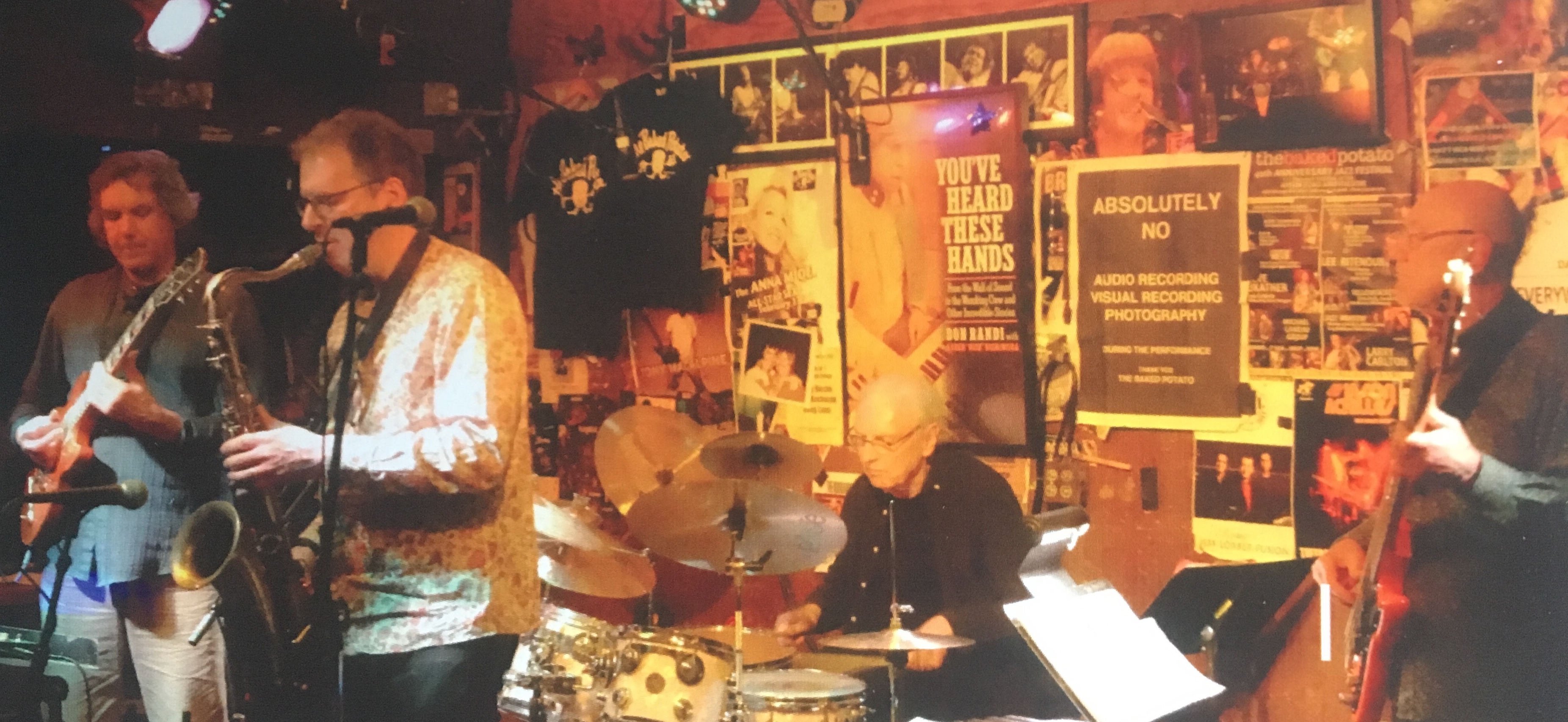

* The CD reissue of Centipede’s Septober Energy is on the Esoteric label. I don’t know who took the photograph at the Lyceum show.