Fat John & John Burch

In the UK between about 1962 and 1964 you could detect, beneath the excitement of the Beat Boom, the emergence of a music that made anything seemed possible. Largely inspired by the Charles Mingus of Blues & Roots and Oh Yeah!, a new generation of British musicians applied jazz techniques to the form and spirit of the blues in an effort to give their music a strong emotional impact. The nodal point for this was Alexis Korner’s Blues Incorporated, in which a guitarist who loved the music of the Delta chose to surround himself with a shifting cast of younger players who were listening to Mingus, Coltrane and Ornette. When these musicians moved on, some of them became a powerful force in the British rock movement of the late ’60s and early ’70s.

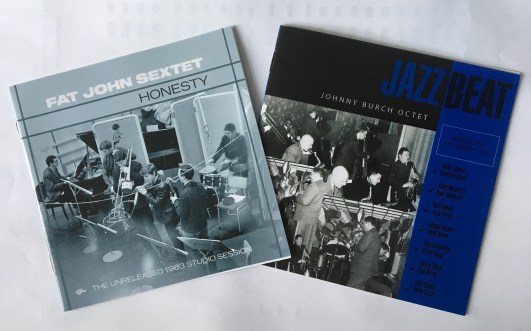

The transitional period didn’t last long. Some of its most interesting bands never got beyond the clubs and pubs and the occasional BBC radio broadcast, and didn’t even get as far as releasing a record. That’s partially rectified by the appearance of new collections of mostly unheard music from two of them: the Fat John Sextet, led by the drummer John Cox, and the octet of the pianist John Burch.

Cox, born in Bristol in 1933, wasn’t all that fat; he was useful drummer who started out as a bandleader in London with a group playing “half mainstream, half trad”. That changed quite quickly. In 1962, with John Mumford on trombone and Dave Castle on alto, they had a Monday-night residency at the Six Bells in Chelsea, playing music of a more contemporary cast. Art Blakey’s “Theme” was among the three tracks they recorded at the Railway Hotel in West Hampstead for a Decca compilation titled Hot Jazz, Cool Beer. In December 1963, when they recorded an unreleased session at the Pye studio just off Marble Arch, the line-up featured Chris Pyne on trombone, Ray Warleigh on alto and flute, Tony Roberts on tenor, Pete Lemer on piano and the great Danny Thompson on bass.

Those two sessions make up Honesty, a new 2CD set that is, I think, the only memorial to John Cox’s career. The 75-minute Pye session includes such standards-to-be as Herbie Hancock’s “Watermelon Man”, Horace Silver’s “Sister Sadie”, Benny Golson’s “Whisper Not” and Junior Mance’s lovely “Jubilation”, indicating that the prevailing wind was blowing from a hard-bop direction, with occasional gusts of soul. More than half a century later, it holds up well. And while any opportunity to hear Warleigh’s eloquence is not to be missed, it’s also good to be reminded of what a very expressive player Tony Roberts has always been, and how scantily represented he is on record (Henry Lowther’s Child Song and Danny Thompson’s Whatever and Whatever Next being the only examples that spring to my mind). This is fine post-bop jazz with a hint, in Mingus’s “My Jelly Roll Soul” and the Latin rhythms of which Cox was fond, of how the music would have sounded in a more informal live setting .

Pyne, Warleigh and Thompson had all been members of Blues Incorporated. So had Graham Bond, Jack Bruce and Ginger Baker, who appear on Jazz Beat, by the Johnny Burch Octet. A fourth member of both Burch’s and Korner’s bands, the saxophonist Dick Heckstall-Smith, was committed elsewhere when the band recorded a BBC Jazz Club session in 1963. Stan Robinson depped for him, joining a front completed by Mike Falana (trumpet), John Mumford (trombone), Bond (alto) and Miff Moule (baritone), with a rhythm section of Burch (piano), Bruce (double bass) and Baker (drums).

The music here has a rougher edge (and has survived with an appropriately raw sound quality) and at times it can be electrifying. I remember hearing this broadcast, and the version of “Early in the Morning” — a work song borrowed from Murderers Home, the Alan Lomax recording of prisoners’ songs at Parchman Farm — stayed with me through the decades until I heard it again. Apparently arranged (very effectively) by Baker, it was also in Blues Incorporated’s repertoire. Here it inspires good solos from all the horns and an absolutely incendiary one from Bond, very much on the form he showed a year or two earlier on Don Rendell’s Roarin’. Brewing up a fusion of Cannonball Adderley’s soulfulness and Eric Dolphy’s out-there angularity, he shows here what was lost when his instincts and appetites led him elsewhere. Burch’s nice arrangements of Bobby Timmons’ “Moanin'” and Jimmy Heath’s “All Members” are other highlights of this session. Two years later Burch led a different line-up on a BBC Band Beat session. The mood on tracks like “The Champ”, “Oleo”, “Milestones” and “Stolen Moments” is relatively restrained by comparison with that of the Bond/Bruce/Baker line-up, but there is fine work from Hank Shaw (trumpet), Ken Wray (trombone), Ray Swinfield (alto) and Peter King on tenor, and the bass is in the hands of the young Jeff Clyne. The approach is more polished, and the fidelity is higher.

The vinyl version of Jazz Beat has eight tracks, three from the first session and five from the second. The CD has six from 1963 and lots of outtakes from the later broadcast, including Tony Hall’s introductions. I wrote the sleeve note but since no money changed hands I feel no embarrassment in drawing your attention to a release that, along with the Fat John CD, helps to fill an important gap in the history of British jazz. Within a short time, of course, some of the people featured on these records were taking their place in bands heard around the world.

Neither of the leaders is still with us. To judge from Simon Spillett’s notes for Honesty, Fat John led an eventful life after his career in jazz came to an end. Burch, a year older than Cox, died in 2006, his life having been made reasonably secure by the royalties from a song called “Preach and Teach”, which appeared on the B-side of “Yeh Yeh”, Georgie Fame’s No 1 hit, earning as much in songwriting royalties as the A-side. Many deserve a break like that; few get it.

* Honesty is out now on Turtle Records. Jazz Beat is on the Rhythm and Blues label: the LP came out on Record Store Day and the CD is released on April 26.