A soundtrack of the ’60s, Italian-style

The Jazz on Film series of compilations, curated with excellent taste and scrupulous attention to detail by Selwyn Harris, might be the best reissue programme since Hip-O Select’s Complete Motown Singles treasury. My favourites so far have been the French New Wave and Jazz in Polish Cinema boxes, but I’m very pleased to have the new vinyl single-album release titled Jazz in Italian Cinema, which collects soundtracks from 1958 to 1962 by such composers as Piero Piccioni, Piero Umiliani, Armando Trovajoli and Giorgio Gaslini.

As you would expect, the 11 tracks are full of atmosphere, mostly that of a smoky bar in Trastevere during the period when Italy was emerging the from the wartime ruins and making its own adaptation of the American culture disseminated by the occupying US forces. It begins with a track from Umiliani’s score for Marco Monicelli’s I Soliti Ignoti (released in the English-speaking world as Big Deal on Madonna Street), setting the tone for most of the set with an approach based on Miles Davis’s Birth of the Cool band and Shorty Rogers’ medium-sized units.

Chet Baker, staying in Italy during one of his periods of personal turmoil, is featured on two tracks written by Trovajoli for Dino Risi’s Il Vedovo; sounding forlorn on “Oscar Is the Back” and sprightly on the film’s theme tune, he plays with poise, concentration and inventiveness. He’s even better on “Tensione”, the first of two tracks from Umiliani’s score for Nanni Loy’s Audace Colpo dei Soliti Ignoti (Fiasco in Milan), displaying the kind of up-tempo chops that suggest why Charlie Parker was so impressed when they played together in Los Angeles in 1952. “Relaxing’ with Chet”, the second of the tracks, is a lovely West Coast-style medium swinger.

Piccioni’s theme for Elio Petri’s L’Assassino (which starred Marcello Mastroianni) sounds charmingly like the sort of stealthy thing Henry Mancini, in a jazz mood, might have written for a detective movie. Gino Marinacci on baritone saxophone, the composer on piano an unidentified vibraphonist are the excellent soloists. No musicians are identified on Piccioni’s “Finale”, from Antonio Pierangeli’s Adua e le Compagne (Adua and Her Friends), which is a shame since it features some exceptional alto saxophone work from a player whose fluency and bitter-sweet tone are somewhere between Hal McCusick and John Handy. “Blues all’Alba” from Giorgio Gaslini’s quartet music for Michelangelo Antonioni’s La Notte is probably the best known piece here, a cigarettes-and-coffee nocturne featuring Eraldo Volonté’s eloquently world-weary tenor saxophone.

Next comes the only letdown: John Lewis’s “In a Crowd”, from Eriprando Visconti’s Una Storia Milanese (A Milanese Story), which teams good jazz players — guitarist René Thomas, flautist Bobby Jaspar and Lewis himself — with a string quartet but never emerges from behind a veil of effeteness. But Harris has saved the biggest surprise for last: two delightful tracks by by altoist Sandro Brugnoli and his Modern Jazz Gang from the soundtrack to Enzo Battaglia’s Gli Arcangeli (The Archangels), good examples of robustly swinging, bluesy post-bop jazz with modal inclinations neatly arranged for octet, in which Cicci Santucci’s bright-toned trumpet and Pucci Sboto’s vibes heard to good advantage.

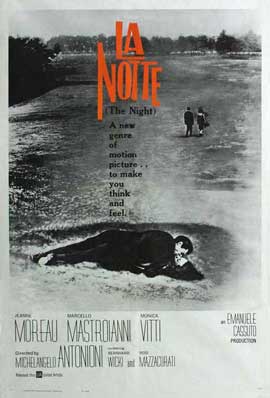

All that, then, and a beautiful black and white shot of Jeanne Moreau on the front cover. A very entertaining and enlightening set, then — and, as the sleeve notes suggest, there’s potentially much more where this came from.